Common bats of Big Bend National Park

This article was researched and written by a student at Texas Tech University participating in the Encyclopedia of Earth's (EoE) Student Science Communication Project. The project encourages students in undergraduate and graduate programs to write about timely scientific issues under close faculty guidance. All articles have been reviewed by internal EoE editors, and by independent experts on each topic.

Contents

Introduction

Big Bend National Park, located in westernTexas, USA is home toover twenty species of bats, most of which are uncommon and/or endangered. A few species, however, are quite common in the park so visitors are likely to see them. In desert ecosystems, such as in Big Bend National Park (Common bats of Big Bend National Park) , bats are a major pollinator of cacti and other flowering plants and a major consumer of flying insects.

Western Pipistrelle (Pipistrellus hesperus)

Description

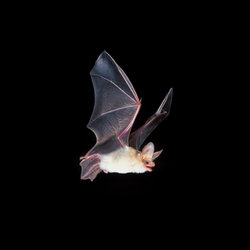

The Western Pipistrelle, also known as the Canyon Bat, is a small light gray brown bat with a black leathery facial mask. Their wings, ears, and legs are also black. Their tragus (a short fleshy projection that covers the entrance of the ear) is short and blunt. These are the smallest bats found in North America, averaging 66 mm long with 28 mm forearms. They weigh only between three to six grams.

Habitat and Habits

Western Pipistrelle live in arid desert habitats ranging from Michoacan and Hildalgo, Mexico, up into southern region of the state of Washington. Roosting in small crevices in canyon walls during the day, Western Pipistrelles are usually the earliest to emerge in the evening.During the daytime, some occupy rodent burrows andothers roost underneath rocks. During the night, they fly slowly, feeding on ants, mosquitoes, fruit flies, and leafhoppers. After consuming up to 20% of their body weight in insects, the bats return to their roost at dawn. In cold winter months, Western Pipistrelle hibernate in their crevices, only emerging on warmer days to forage for insects and water. Females give birth in May and June to two pups, sometimes only one, in separate small roosts containing fewer than twenty other females.

Threats to the Species

Because these bats prefer living in small crevices, they are drawn to mines and sometimes construction sites. Destruction through land development is limiting roosting sites and displacing populations.

Townsend’s Big-Eared Bat (Plecotus townsendii)

Description

The Townsend’s Big-Eared bat is a brown medium sized bat with lighter undersides. Prominent features include the glandular outgrowths on each side of the snout and large flexible ears. On average, they are around 100 mm long, with each forearm roughly 44 mm long and ears are up to 35 mm long. They weigh between seven to twelve grams.

Habitat and Habits

Townsend’s Big-Eared bats inhabit old abandoned mines, tunnels, caves, and sometimes old buildings. Their habitat ranges are in coniferous forests, mixed meso-phytic forests, deserts, native prairies, riparian communities, active agricultural areas, and coastal areas. While these mammals prefer roosting solitarily, females congregate in small groups during breeding season. During the winter, the bats do not migrate but instead hibernate. They are unfortunately extremely vulnerable while hibernating because of their sensitivity to humidity and temperature change. During their active season Townsend’s Big-Eared bats forage late in the night on moths, beetles, flies, wasps, and, most commonly, lepidopterans. Females give birth in mid-June to one, two, or even three pups, however, twins are the most common.

Threats to the Species

Even though the Townsend’s Big-Eared bat is listed as a Species of Special Concern by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, these bats are found in abundance in the Rio Grande area. Their biggest threat is the loss and destruction of important roosting and or feeding sites. Pesticides used in agriculture are killing their preferred insect prey, timber harvesting practices are removing habitats, and abandoned buildings are being torn down, mostly because bats are commonly seen as pests. Because these bats are sensitive to disturbances, roosts are commonly abandoned after human contact, so it is important to remain outside of their environment.

Pallid Bat (Antrozous pallidus)

Description

Pallid Bats are relatively large, yellowish-brown bats with long broad ears that have several transverse lines. They have a lighter spot between their shoulders and lighter toned undersides. The membrane making up their wing is brown and nearly naked of fur. A prominent facial feature is the blunted snout. Pallid bats are up to 113 mm long, have 28 mm long ears, 48 mm long forearms, and weigh between 12 and 17 grams.

Habitat and Habits

Pallid Bats inhabit rock crevices, caves, mine tunnels, attics of houses, under the eaves of barns, behind signs, in hollow trees, and in abandoned adobe buildings. Colonies are rarely large, containing only 12-100 bats. Pallid bats usually forage late at night, well after dark. It is suspected that the species migrates down into Mexico during winter even though some bats are spotted remaining in the United States. Pallid Bats have uncommon feeding habits for a bat species. The most prevalent items in their diet are large, night-flying insects and ground-dwelling arthropods. Up to fifty four different insects have been found in the stomachs of these bats. This range in diet is contributed to the bats combination of aerial and terrestrial feeding. Mating occurs in early summer and females give birth during May to mid-June to up to four pups. The most common, however, is two pups.

Threats to the Species

Habitat is being lost through timber harvesting for suburban expansion and land development. Abandoned mines are becoming shut down, and human vandalism is displacing populations. Their greatest threat is the needless killing by humans. People are exterminating these bats from their barns and property because they assume that the bats are harmful. Pallid Bats consume large amounts of crop pests that commonly plague farmers.

Brazilian Free-tailed Bat (Tadarida brasiliensis)

Description

The Brazilian Free-tailed Bat, also known as the Mexican Free-tailedBat,is a medium sized bat with reddish black fur. These mammals have broad ears lined with wart-like protrusions. They have a second joint on their fourth finger that is 6-9 mm long, and their feet have distinct white bristles on the sides of outer and inner toes. Their total length is 95 mm long with 19 mm long ears, 42 mm long forearms, and they weigh between 11 and 14 grams.

Habitat and Habits

Brazilian Free-tailed Bats roost in caves, mine tunnels, old wells, hollow trees, human habitations, bridges, and other buildings. They are frequently called “house bats” because they will live in hollowed roofs, spaces between downtown buildings, attics, narrow spaces between signs and buildings, and spaces in the walls of buildings. Brazilian Free-tailed Bats are considered one of the most abundant mammals in North America and the most abundant mammalian species in the Western hemisphere, with many millions of individuals arrivcing from Mexico each season. The bats emerge at night to feed on moths, beetles, flying ants, and June bugs as their sole source of food. Mating takes place in early spring, and females give birth in mid-June toonly one pup. Their offspring are different than other bat species in that they are born furless and unable to fly. The newborns are placed in specific places on the colony ceiling while adults leave to feed. Offspring are fully independent, however, within a month after birth.

Threats to the Species

A major threat to this species is pesticide poisoning. These bats eat thousands of agricultural pasts each night, causing a buildup of poisonous chemicals in their bodies. The most serious reason for decline is from human trespassing and vandalism to caves where millions of bats may live. Eradication from humans because of over exaggerated threats of rabies is also reducing roosts.

References and Further Reading

- Brazilian Free-Tailed Bat The Mammals of Texas- Online Edition

- Pallid Bat The Mammals of Texas- Online Edition

- Townsend's Big-Eared Bat The Mammals of Texas- Online Edition