Volcanoes/Volcanic minerals

< Volcanoes

Volcanic minerals are the ones expected to be found in volcanic rocks.

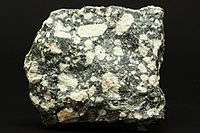

Amphiboles

Def. a group of monoclinic or orthorhombic double chain inosilicates with the general formula of

- X2Y5Z8O22(OH)2 where

- X is magnesium, ferrous iron (Fe2+), calcium, lithium, sodium, and ferric iron (Fe3+)

- Y is Al, Mg, or Fe or less commonly Mn, Cr, Ti, Li, etc.

- Z is chiefly Si or Al

is called an amphibole.

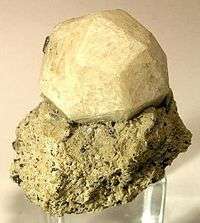

Andalusites

Although andalusite is a metamorphic mineral, it also occurs as in the specimen on the right in volcanic rocks.

Epidotes

Epidote is another usually metamorphic mineral that can occur in volcanic rocks.

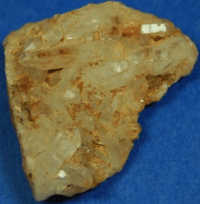

Feldspars

Def. "[a]ny of a large group of ... aluminum [tectosilicates] of the alkali metals sodium, potassium, calcium and barium"[1] is called feldspar.

As the sample on the right shows two different cooling rates even in volcanic rocks can yield euhedral feldspar crystals (light yellow) in a rhyolite (tiny crystal) matrix.

Plagioclases

Def. "[a]ny of a group of aluminum silicate feldspathic minerals ranging in their ratio of calcium to sodium"[2] is called plagioclase.

Feldspathoids

Volcanic sources that have a low silica concentration are more likely to produce feldspathoid-containing rocks than feldspar-containing rocks.

Feldspathoid volcanic rocks occur in "a suite of basanites, olivine nephelinites, and olivine melilite nephelinites from the Raton-Clayton volcanic field, New Mexico."[3]

"Volcanism in the Raton-Clayton field commenced approximately 7.5 Ma ago with the eruption of alkali basalts and continued intermittently until at least 10,000 y.a. with the eruption of the Capulin Mountain silicic alkalic basalt (Stormer 1972a; Baldwin and Muehlberger 1959). The entire volcanic sequence was erupted onto the high plains east of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, and as such, represents the eastern limit of late Cenozoic volcanism in the western U.S. Volcanic activity in the Raton-Clayton field was contemporaneous with volcanism in the Rio Grande rift, and the Raton-Clayton volcanic field is interpreted as part of the Rio Grande rift system."[3]

Garnets

"Abundances of rare earth elements, Hf, Sc, Co, Cr and Th in garnet megacrysts and their volcanic hosts or matrices are used to estimate garnet/liquid partition coefficients for these elements."[4]

"The wide variation in garnet/liquid partition coefficients from kimberlites to rhyolites cannot be explained as an effect of temperature and we conclude that a major factor is the composition of the melt from which the garnet crystallized."[4]

Vesuvianites

"Minerals such as harkerite, wilkeite, cuspidine, cancrinite, vesuvianite and phlogopite indicate the intrusive melt had a high volatile content which is in agreement with the very high explosivity index of this volcanic district."[5]

Kyanites

"Volcanoes of the Eifel district have sampled the total crust. [...] Types with chlorite + clinozoisite + oligoclase, with chlorite + garnet + biotite + clinozoisite + oligoclase lead to types with garnet + clinozoisite within garnet but none outside, kyanite + staurolite + almandite + oligoclase."[6]

Micas

Def. a group of monoclinic phyllosilicates with the general formula[7]

- X2Y4–6Z8O20(OH,F)4

- in which X is K, Na, or Ca or less commonly Ba, Rb, or Cs;

- Y is Al, Mg, or Fe or less commonly Mn, Cr, Ti, Li, etc.;

- Z is chiefly Si or Al, but also may include Fe3+ or Ti;

- dioctahedral (Y = 4) and trioctahedral (Y = 6)

is called a mica.

Olivines

Def. "[a]ny of a group of olive green magnesium-iron" orthosilicates "that crystallize in the orthorhombic system"[8] is called an olivine.

At right is a visual close up of green sand which is actually olivine crystals that have been eroded from lava rocks. Some olivine crystals are still inside the lava rock.

"Forsterite (Mg2SiO4) is the magnesium rich end-member of the olivine solid solution series."[9]

"Forsterite is associated with igneous and metamorphic rocks and has also been found in meteorites. In 2005 it was also found in cometary dust returned by the Stardust probe.[10] In 2011 it was observed as tiny crystals in the dusty clouds of gas around a forming star.[11]"[9]

"Two polymorphs of forsterite are known: wadsleyite (also orthorhombic) and ringwoodite (isometric). Both are mainly known from meteorites."[9]

Pyroxenes

Def. a group of monoclinic or orthorhombic, single chain inosilicates with the general formula of X Y(Si,Al)2O6, where

- X is calcium, sodium, ferrous iron (Fe2+), magnesium, zinc, manganese and lithium;

- Y is chromium, aluminum, ferric iron (Fe3+), magnesium, manganese, scandium, titanium, vanadium, and ferrous iron (Fe2+)

is called a pyroxene.

"The pyroxenes are a group of important rock-forming inosilicate minerals found in many igneous and metamorphic rocks. They share a common structure consisting of single chains of silica tetrahedra and they crystallize in the monoclinic and orthorhombic systems. Pyroxenes have the general formula XY(Si,Al)2O6 (where X represents calcium, sodium, iron+2 and magnesium and more rarely zinc, manganese and lithium and Y represents ions of smaller size, such as chromium, aluminium, iron+3, magnesium, manganese, scandium, titanium, vanadium and even iron+2). Although aluminium substitutes extensively for silicon in silicates such as feldspars and amphiboles, the substitution occurs only to a limited extent in most pyroxenes."[12]

At right is an image of a very rare, sharp, complete-all-around pyroxene is from Ducktown District, Polk County, Tennessee, USA, circa mid to late 1800s.

Quartzes

Red "thermoluminescence (RTL) emission from quartz, as a dosimeter for baked sediments and volcanic deposits, [from] older (i.e., >1 Ma), quartz-bearing known age volcanic deposits [can use as standards] independently-dated silicic volcanic deposits from New Zealand, ranging in age from 300 ka through to 1.6 Ma."[13]

Alpha quartzes

Def. "a continuous framework [tectosilicate] of SiO4 silicon–oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall [chemical] formula [of] SiO2 ... [of] trigonal trapezohedral class 3 2"[14], usually with some substitutional or interstitial impurities, is called α-quartz.

When the concentration of interstitial or substitutional impurities becomes sufficient to change the space group of a mineral such as α-quartz, the result is another mineral. When the physical conditions are sufficient to change the solid space group of α-quartz without changing the chemical composition or formula, another mineral results.

"Shocked quartz is associated with two high pressure polymorphs of silicon dioxide: coesite and stishovite. These polymorphs have a crystal structure different from standard quartz. Again, this structure can only be formed by intense pressure, but moderate temperatures. High temperatures would anneal the quartz back to its standard form."[15]

"Short-rived bottle-green or blue luminescence colours with zones of non-luminescing bands are very common in authigenic quartz overgrowths, fracture fillings or idiomorphic vein crystals. Dark brown, short-lived yellow or pink colours are often found in quartz replacing sulphate minerals. Quartz from tectonically active regions commonly exhibits a brown luminescence colour. A red luminescence colour is typical for quartz crystallized close to a volcanic dyke or sill."[16]

Referring to the image on the right: "Lake County experienced incredible volcanic activity. The heat melted the quartz but temperatures and pressures were just right so it was not destroyed. Rather, the melted quartz was carried along with the lava flows."[17]

Beta quartzes

Beta quartz (β-Quartz) is stable "between 573° and 870°C"[18].

Seifertites

Def. a polymorph of α-quartz formed at an estimated minimum pressure of 35 GPa up to pressures above 40 GPa with a orthorhombic space group Pmmm no. 47 is called seifertite.[19]

Tridymites

Def. a polymorph of α-quartz formed at temperatures from 22-460°C with at least seven space groups for its forms with tabular crystals is called tridymite.[20]

Coesites

Alpha-quartz (space group P3121, no. 152, or P3221, no. 154) under a high pressure of 2-3 gigapascals and a moderately high temperature of 700°C changes space group to monoclinic C2/c, no. 15, and becomes the mineral coesite.

Coesite is "found in extreme conditions such as the impact craters of meteorites"[21].

Stishovites

Def. a polymorph of α-quartz formed by pressures > 100 kbar or 10 GPa and temperatures > 1200 °C is called stishovite.[22]

Stishovite may be formed by an instantaneous over pressure such as by an impact or nuclear explosion type event.[15]

"[M]inute amounts of stishovite has been found within diamonds[23]"[22].

Cristobalites

Def. a high-temperature (above 1470°C) polymorph of α-quartz with cubic, Fd3m, space group no. 227, and a tetragonal form (P41212, space group no. 92) is called cristobalite.[24]

Sillimanites

Staurolites

Wollastonites

Research

Hypothesis:

- Volcanic minerals can be formed at room temperature using electrochemistry.

Control groups

The findings demonstrate a statistically systematic change from the status quo or the control group.

“In the design of experiments, treatments [or special properties or characteristics] are applied to [or observed in] experimental units in the treatment group(s).[25] In comparative experiments, members of the complementary group, the control group, receive either no treatment or a standard treatment.[26]"[27]

Proof of concept

Def. a “short and/or incomplete realization of a certain method or idea to demonstrate its feasibility"[28] is called a proof of concept.

Def. evidence that demonstrates that a concept is possible is called proof of concept.

The proof-of-concept structure consists of

- background,

- procedures,

- findings, and

- interpretation.[29]

See also

- Igneous minerals

- Metamorphic minerals

- Minerals

- Sedimentary minerals

References

- ↑ "feldspar, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. October 16, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ↑ "plagioclase, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. October 16, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- 1 2 David W. Phelps, David A. Gust, and Joseph L. Wooden (November 1983). "Petrogenesis of the mafic feldspathoidal lavas of the Raton-Clayton volcanic field, New Mexico". Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 84 (2-3): 182-90. doi:10.1007/BF00371284. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00371284. Retrieved 2016-02-12.

- 1 2 Anthony J. Irving and Frederick A. Frey (June 1978). "Distribution of trace elements between garnet megacrysts and host volcanic liquids of kimberlitic to rhyolitic composition". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 42 (6): 771-87. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(78)90092-3. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0016703778900923. Retrieved 2016-02-12.

- ↑ G. Cavarretta and F. Tecce (1987). "Contact metasomatic and hydrothermal minerals in the SH2 deep well, Sabatini volcanic district, Latium, Italy". Geothermics 16 (2): 127-45. doi:10.1016/0375-6505(87)90061-7. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0375650587900617. Retrieved 2016-02-12.

- ↑ G. Voll (1983). Karl Fuchs, Kurt von Gehlen, Hermann Mälzer, Hans Murawski, and Arno Semmel. ed. Crustal Xenoliths and Their Evidence for Crustal Structure Underneath the Eifel Volcanic District, In: Plateau Uplift. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 336-42. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-69219-2_37. ISBN 978-3-642-69221-5. http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-69219-2_37. Retrieved 2016-02-12.

- ↑ Deer, W. A., R. A. Howie and J. Zussman (1966) An Introduction to the Rock Forming Minerals, Longman, ISBN 0-582-44210-9

- ↑ "olivine, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. August 30, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- 1 2 3 "Forsterite, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. October 24, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- ↑ Ds. Lauretta, L.P. Keller, S. Messenger (2005). "Supernova olivine from cometary dust". Science 309 (5735): 737–741. doi:10.1126/science.1109602. PMID 15994379.

- ↑ Spitzer sees crystal 'rain' in outer clouds of infant star, Whitney Clavin and Trent Perrotto, Physorg.com, May 27, 2011 . Accessed May 2011

- ↑ "Pyroxene, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. February 21, 2013. Retrieved 2013-09-01.

- ↑ M. Fattahi and S. Stokes (December 2000). "Extending the time range of luminescence dating using red TL (RTL) from volcanic quartz". Radiation Measurements 32 (5-6): 479-85. doi:10.1016/S1350-4487(00)00105-0. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1350448700001050. Retrieved 2016-02-12.

- ↑ "Quartz, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. October 22, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- 1 2 "Shocked quartz, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. May 14, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ↑ K. Ramseyer, J. Baumann, A. Matter and J. Mullis (December 1988). "Cathodoluminescence Colours of α-Quartz". Mineralogical Magazine 52 (368): 669-77. doi:10.1180/minmag.1988.052.368.11. http://www.minersoc.org/pages/Archive-MM/Volume_52/52-368-669.htm. Retrieved 2016-02-12.

- ↑ Basham Jewelry (2006). "Lake County Diamonds". Lake County, California USA: FreeWebs.com. Retrieved 2016-02-12.

- ↑ Willard Lincoln Roberts, George Robert Rapp, Jr., and Julius Weber (1974). Encyclopedia of Minerals. 450 West 33rd Street, New York, New York 10001 USA: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company. pp. 693. ISBN 0-442-26820-3.

- ↑ "Seifertite, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. December 5, 2011. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ↑ "Tridymite, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. August 25, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ↑ "coesite, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. August 3, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- 1 2 "Stishovite, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. October 24, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ↑ R Wirth, C. Vollmer, F. Brenker, S. Matsyuk, F. Kaminsky (2007). "Inclusions of nanocrystalline hydrous aluminium silicate "Phase Egg" in superdeep diamonds from Juina (Mato Grosso State, Brazil)". Earth and Planetary Science Letters 259 (3–4): 384. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2007.04.041.

- ↑ "Cristobalite, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. June 26, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ↑ Klaus Hinkelmann, Oscar Kempthorne (2008). Design and Analysis of Experiments, Volume I: Introduction to Experimental Design (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-72756-9. http://books.google.com/?id=T3wWj2kVYZgC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ R. A. Bailey (2008). Design of comparative experiments. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68357-9. http://www.cambridge.org/uk/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521683579.

- ↑ "Treatment and control groups, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. May 18, 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-31.

- ↑ "proof of concept, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. November 10, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ↑ Ginger Lehrman and Ian B Hogue, Sarah Palmer, Cheryl Jennings, Celsa A Spina, Ann Wiegand, Alan L Landay, Robert W Coombs, Douglas D Richman, John W Mellors, John M Coffin, Ronald J Bosch, David M Margolis (August 13, 2005). "Depletion of latent HIV-1 infection in vivo: a proof-of-concept study". Lancet 366 (9485): 549-55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67098-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1894952/. Retrieved 2012-05-09.

External links

![]() This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

| |

Development status: this resource is experimental in nature. |

| |

Educational level: this is a research resource. |

| |

Resource type: this resource is an article. |

| |

Resource type: this resource contains a lecture or lecture notes. |

| |

Subject classification: this is a Geology resource. |