Understanding: Example

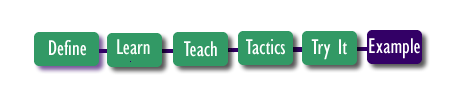

Back to Topic:Instructional Design > Cognitive behaviors > Understanding Concepts > Define > Learn > Teach > Tactics > Try It > Example

Source: Understanding Understanding by Charles M. Reigeluth. Used by Permission.

Learning Activity

Decide What to Teach

Imagine your friend, Jennifer, has just found out that her student, Sam, needs to learn what a revolution is (as in a revolutionary war). She knows that it is important for him and that he does not already know what it is. She realizes that the methods she used to to teach him the names of the Presidents of the United States in Module 2: Invariant Tasks, won't work very well here, but she doesn't know what to do. So she has come to you for more advice.Decide How to Teach

You, of course, know that a revolution is an armed uprising against a ruling authority; that to be a revolution rather than a rebellion, it must be widespread; and that to be a revolution rather than an invasion, it must be waged by people within the territory of the ruling authority (government). You can see right away that this is the conceptual understanding type of learning.

Based on what you now know about how this kind of learning occurs, what do you think you should advise Jennifer to do first?

Assure Prior Knowledge has been Acquired

Given the importance of relating the new knowledge to relevant prior knowledge, Jennifer must figure out what the important prior knowledge is and whether or not Sam has already acquired it. If he hasn't, then she must remediate -- teach that missing knowledge -- before she teaches what a revolution is. Certainly, Sam must know what fighting is and, more specifically, an armed fight. He also must know what a ruling authority is and what the territory of a ruling authority is. Of course, these labels do not need to be learned -- it is the ideas behind them which must be understood. These ideas are prerequisites in the sense that they must be understood before it is possible for one to understand what a revolution is.

Give the Presentation

First, Jennifer assessed Sam's needs and found out that he should be taught what a revolution is. Next, we have seen that she must assure mastery of relevant prior understandings. But then what should she do? Remember that Bloom identified learner participation as perhaps the most important determinant of the quality of instruction. Also remember that presentation, practice, and feedback have proven to be routine components for both memorization and skill application, although the nature of each routine component is quite different for each kind of learning. Given all of this, what are the most important recommendations you could give to Jennifer for teaching what a revolution is?

Certainly the knowledge needs to be presented in some form to Sam. Learner participation of some kind also makes sense. But how should the knowledge be presented? And what form should the participation take?

Let's start by thinking about what needs to be presented. Remember the principles of learning. According to Ausubel, Sam must have a good "subsumer", a broader and more inclusive idea which is closely related. In other words, Jennifer should provide a meaningful context for understanding "revolution". What would such a subsumer be in this case? Well, a revolution is a kind of war, and a kind of fighting. But war is a closer concept to revolution, because there are many other kinds of fighting besides wars. Therefore, "war" will make it easier to understand what a revolution is. This makes it a more appropriate subsumer.

But for sure Sam knows what a war is, so what does all this have to do with the presentation? Well, Jennifer should start by activating the meaningful context: "Sam, you know what a war is." Then she should relate the new knowledge to it (superordinate knowledge): "A revolution is a kind of war." Next, she can describe what a revolution is, using terms that are familiar to Sam. This entails analyzing it as to its critical attributes (subordinate parts). She can describe an example or two (experiential knowledge). She can compare and contrast it to other kinds of wars (coordinate knowledge). And if Sam was already familiar with any kinds of revolutions (subordinate knowledge), she could relate it to them. (For example, in teaching what a vertebrate is, she could relate vertebrates to dogs, people, horses, fish, and so on.) She could even come up with an analogy, like convicts revolting in a prison. And she could infer the causes of revolutions, or trace the implications if a certain revolution had never occurred.

Provide Practice

But what about learner participation? Well, as far as practice is concerned, Jennifer can ask Sam to explain in his own words what a revolution is. Or she can ask him to explain in his own words the differences between a revolution and an invasion (which was already explained to him). But such "regurgitation" questions don't require much depth of processing. How do you think Jennifer could help cause greater depth and breadth of processing?

Provide Enhancement as Needed

Practice isn't the only kind of learner participation. As was discussed in Module 7, discovery learning is a form of learner participation. What are the differences between inductive and deductive participation?

Deduction could take a number of forms. Breadth of processing can be increased by creating links with other meaningful knowledge the learner already possesses. Asking the learner to paraphrase what has already been presented (which we identified as shallow questioning above) does not usually create any additional links; it usually just strengthens those which already exist. Hence, it is a relatively superficial form of deduction -- that is, it does not cause broader processing. On the other hand, elaboration does create additional links. Elaboration is the process of relating additional knowledge to what one has already learned. This is done deductively when the relationships are told to the learner.

Induction is a bit different for understanding than it is for application of principles. It is basically discovery learning, as it is for application. But its role for understanding is to get the learner to process the knowledge fairly deeply. If Jennifer compares and contrasts revolution with coordinate concepts for Sam, he is not likely to process it as deeply as if she asks him to do it: "What do you think is the difference between a revolution and an invasion?" and "What do you think is the difference between an uprising and a revolution?" and "In what ways is a prison revolt similar to a revolution, and in what ways is it different?"Feedback

Naturally, feedback is very important here. This form of guided discovery should not take much longer than telling the relationships to the learner. On the other hand, pure discovery would certainly take much longer and might not result in the learner learning anything new at all. Hence, it does not seem likely that pure discovery would present any advantages over this form of guided discovery, or "figure-out" approach to instruction.

Your Task

Your task is to add one idea for improving the learning activity that aligns with the instructional principles associated with enhancing understanding.

- In order to get Sam to "understand" about the Presidents, telling him the information which enables him to explain why the Presidents took certain actions would be great. The information is such as information about the Presidents' personalities and the context and the situation of the States and the rest of the world when the Presidents were in the position. Kei (discuss • contribs) 06:18, 19 February 2014 (UTC)

- Instead of saying, "Sam you know what a war is" accessing his prior knowledge by having him explain to you what a war is. This way you are accessing his prior knowledge and you can set the discussion in relevant examples that are personally meaningful to Sam. Maybe Sam's uncle was in a war and that can be the opportunity to build on his current schemata. gdysard 21:25, 15 (EST) February 2014

- I would enhance Sam's understanding of the concept by relating it to subordinate knowledge. I would have him read short summaries of the American Revolutionary War and Civil War and determine which war is a revolution and why. Once he accomplished this, I would have him repeat the activity by analyzing the recent revolutions in Egypt and Tunisia. Hatch.nicole 20:38, 29 January 2012 (UTC)

- To be sure that Sam really does understand the differences and similarities between revolutions and rebellions, I would ask him to select one example of a revolution of his choice and one example of a rebellion of his choice. Then I would ask him to create a Venn diagram showing what differences and similarities exist between these two terms. For reinforcement, after the Venn diagram is completed, I would ask him to recount for me how his selected rebellion is a rebellion (according to his Venn diagram) and how his selected revolution is a revolution (again, according to his Venn diagram). For the similarities, Sam would need to show me how those similarities exist in both of his selected examples.Smccorma 03:54, 1 February 2012 (UTC)smccorma

- I would create a card game using many different examples of each concept such as war, invasion, revolution, etc. Sam would then have to catergoize each event under the proper heading, ie. War, Invasion, Revolution.Aabrell 20:57, 2 February 2012 (UTC)

- Jennifer can have Sam relate the concept to coordinate knowledge by asking, first, to compare the concept of revolution to the American Revolution, referencing his own knowledge of American history and Wikipedia entries as necessary, and then contrasting with the ongoing war in Afghanistan, and asking him to explain how Afghanistan is or is not a revolution. She can reinforce the comparison/contrast by asking him to explain the role of the United States government in each of the two wars. Finally, she can ask him to draw a representative picture to illustrate the meaning of both the American Revolution and the war in Afghanistan. Kevmcgra 19:36, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- I would give instances of invasion, revolution, and rebellion, and ask Sam to distinguish those instances and give me a reason to let him compare and contrast each instance and see the difference among the three. Dablee 04:11, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- I would like to suggest giving students more thinking space and participation opportunities during the PRESENTATION process. After explaining the pre-requested concepts, territory, ruling authority, armed uprising, evasion etc., if I were the teacher, I would list these concepts on the blackboard, and play videos of a revolution, a invasion, a rebellion one after another. (tell students which one is which) I would ask students to watch the videos with the question "what's the differences between these wars in terms of territory, ruling authority, and armed uprising?" After they watch the videos, I will let them tell me their comparison and analysis before I make a conclusion and generalize the features of revolutions. Zhaomeng 04:28, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- Jennifer may also show some influences from revolutions, to help Sam understand. For example, the establishment of new political system (like the independence of USA after American Revolution), a cultural or economical shift (like part of the effects of civil war), etc. These should be explained in simple words. Shuya Xu 04:36, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- I would suggest Jennifer to give an example of revolution (like French revolution) first, walk him through the whole event, if necessary, Jennifer could also play him some videos to help him better understand. Then she could give him some other revolutionary examples; leading him to discover what is the common characters for revolution. After Sam understand the concept, Jennifer might also provide him of other Non-revolution examples so that he could know how to distinguish a revolution from rebellion, evasion and other similar concepts. Mayue 03:44, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- Once he understand the superordiante concept of revolution, I would give him different instances of coordinates with their background information such as contexts, the reasons triggering the instances etc which can distinguish one another. After providing Sam with different instances of coordinates with background information, I would give him a authentic scenario which can display one of the instances, and ask him to determine whether it is revolution, rebellion or invasion with his own rationale.Yeolhuh 20:25, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- Coordinate knowledge: giving Sam a list of historical events including revolutions and non-revolutions and allowing Sam to compare, contrast, and choose the ones that involve and align with what a revolution is as well as explain why (paraphrasing/elaborating).Y.Zhang 01:43, 6 February 2012 (UTC)

- I'd suggest Jennifer to show Sam a movie that covers a revolution, or cartoon like The French Revolution cartoon (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eDepJlzaREw). The video will let Sam to think about possible reasons for the revolution, the process, and the result. Songd (discuss • contribs) 03:19, 19 February 2014 (UTC)

- ADD YOUR ANSWER ABOVE THIS BULLET POINT. SIGN IT WITH YOUR NAME USING THE SIGNATURE WIKICODE Phonebein 18:06, 18 December 2011 (UTC)

| Instructional Design | Cognitive Behaviors | < Back |