Time management

This unit is used in: First Line Management and Survey research and design in psychology

Overview

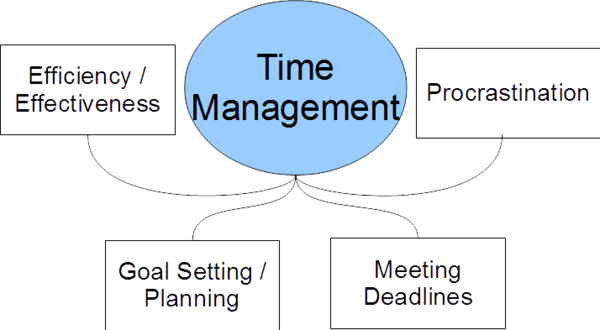

Time management is about managing one's time to execute behaviours required to effectively achieve goals. Thus, time management aims to maximise individual productivity. Time management skills include planning, allocating, setting goals, monitoring and organising the time an individual has to achieve tasks Behaviours include , such as work or academic duties, which are aimed at using time effectively .

There is popular belief that poor allocation of time increases stress and subsequently impairs performance. Time management research indicates that ineffective or ‘poor’ time management can affect productivity in the workplace and have detrimental consequences on an individual’s private life. A meta-analysis of time management research literature found that time management behaviours are associated with increases in job satisfaction, health, and stress reduction . However they noted that the findings in regard to work and academic performance were unclear. Where effects on performance were found, they tended to be positive; however they were often of small effect size or inconsistent significance. Time management is an also effective stress-coping strategy.

Parts of time management are art, and parts are science. Also be aware that time management is a multidimensional concept that can be dissected into many skills and behaviours.

Time management steps

Step 1 - How much time do you have?

First, we have to know how much effective time we have. For instance, if we want time to manage our day at work, we have to figure out how long is available for the work.

This is harder than it appears. You may work an 8 hour day, but it is doubtful that you have 8 hours of effective working time in that day. Meetings, trips to the water cooler, discussions about last nights TV shows all cut into your working time. Many people are interrupted by others when they are working - this can be in the form of phone calls, personal visits or urgent e-mails. If you don't know how much effective time you have, you can do an informal time study. Underestimating the amount of time a task will take (e.g., by failing to account for setting the up, travel time to the location, etc.), or overestimating the amount of time one has to complete the task is a cognitive mistake consistently at the heart of poor time management.

Step 2 - What are the tasks?

This is the simple step - you simply record what you have to do. This can be done on a piece of paper, in an electronic organizer, or in some other form. Make sure it's not just in your head, though - while you might have a fantastic memory, we need the information in some form so we can manipulate it. Pick the form that you are happiest with, as it'll be you that has to work with it.

Step 3 - Prioritization - What is important?

The next step is to ranking the tasks by their importance.

One method is to make three lists, A, B and C:

- A is the list of items to do today;

- B are things that need to be done in the next week or so, and

- C are in the next month or so.

Next, put a number (starting at 1) beside each A list item.

We won't order the B or C list right now.

Step 4 - How much time will each task take?

Go through the list of A tasks and estimate how much time they will each take. Don't worry too much about being perfect, just be as reasonable as you can.

Step 5 - Planning a schedule

Based on the working time available and the estimate of how long each one will take, schedule an order for the tasks.

For example, after meetings and daily tasks, let's say we have 5 hours we can do work. We have 20 tasks, 8 of which are on our A list. Give the 8 tasks an order, and estimate that it will take 1 hour to do each task.

Now, from our plan, we know that we won't finish our A list today. So, we review to see if any of the bottom 3 items is due today (if they were, they should have been a higher priority, but we double check) and then we finalize the ordering, drawing a line after the 5th item (5 items giving us 5 hours of effective work).

Step 6 - Do the work

Do the work.

Step 7 - Review the progress

As soon as we can, after our effective time is up, we review our progress.

We only got through 3 items - item A2 was 2 hours instead of 1 hour, and just as we got started on item A4 we got pulled away for the rest of our effective time for an emergency.

We learned a few things in this example. First, we underestimated item A2 - so similar items should get more accurate in the future. We also learned that 5 hours is the maximum time that we have available, but we might have less. We can cross 3 things off of today's list.

It is important at this stage to avoid thinking of these misestimations, or of the undone tasks, as failures; they aren't. They are, in fact, successes in that they constitute new and important information that you have gained regarding how long those tasks take. This information will be useful to you in the future.

Dimensionality

It has been suggested that time management is a multidimensional construct (e.g., Macan, Shahani, Dipboye, & Phillips, 1990) and psychological research literature has identified some possible factor structures for time management.

In a study of time management skills and learning amongst Spanish students, Garcia-Ros, Pérez-González, and Hinojosa (2004) identified three factors:

- Short-range planning

- Long-range planning

- Time attitudes

One of the more widely accepted models identifies four underlying factors (Macan et al., 1990):

- Setting goals and priorities

- Mechanics of scheduling and planning

- Preference for disorganisation

- Perceived control of time

There is a measurement instrument based on this structure, known as the Time Management Behaviour Scale for which there is some validity evidence (TMBS, Macan et al., 1990). In a meta-analysis by Claessens et al. (2007), it was pointed out that - compared to all models of time management - it was Macan’s (et al. 1990, 1994) models of time management that received the most support in the literature. However, it was also noted that there are some consistency issues and disagreement as to whether perceived control of time should be included (Claessebs et al 2007). Macan went on to argue that the perceived control of time factor is actually an outcome of time management and not a component (Macan, 1994).

A possible factor structure for the 28 time management items in the TUSSTMQ9 is shown in Figure 1.

See also

| |

Search for Time management on Wikipedia. |

- Time management questionnaires

- Procrastination (Motivation and emotion book chapters)

- Time management (Motivation and emotion book chapters)

- Time management project

- Time management references

- University student time management

External links

- Go hard early (icelab)