Stars/Betelgeuse

< Stars

"Betelgeuse [is] a cool (3600 K), large (700 R⊙), rather massive (10–15 M⊙), luminous (> 105 L⊙), and nearby (150 pc) star."[1]

Notations

According to SIMBAD, there are a number of catalog entries and notations that refer to Betelgeuse. Some of these are

- alf Ori, alpha Orionis, α Ori, 58 Orionis, V* alf Ori

- HD 39801,

- HR 2061, and

- SAO 113271, where SAO stands for Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory.

Meteors

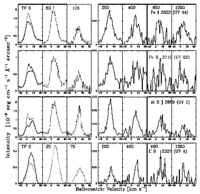

The "Si I λ2516 resonance emission line (Lobel & Dupree 2001) [...] has previously been observed by scanning over the inner chromosphere [of Betelgeuse] at 0, 25, 50, and 75 mas, using a slit size of 100 × 30 mas [the left panel in the graphs on the right]."[2]

"The double-peaked line profiles are observed across the inner chromosphere. The central (self-) absorption core results from scattering opacity in the chromosphere. The asymmetry of the emission component intensities probes the chromospheric flow dynamics in our line of sight. The spectra of GO 9369 are observed across the outer chromosphere using a slitsize of 200 × 63 mas [image on the right]. The profiles beyond 200 mas appear red-shifted with a rather weak short-wavelength emission component. It signals substantial wind outflow opacity in the upper chromoshere, which fastly accelerates beyond a radius of ∼8 R∗."[2]

The set of graphs on the right "compares the profiles of the Si I λ2516 and λ2507 resonance lines (vertical dotted lines are drawn at stellar rest velocity). Both lines share a common upper energy level and their intensities are influenced by pumping through a fluoresced Fe II line. The self-absorption cores of the Si I lines are therefore observed far out, into the upper chromosphere. The shape of these unsaturated emission lines is strongly opacity sensitive to the local chromospheric velocity field. As for the Mg II lines, the outward decreasing intensity of the short-wavelength emission component signals fast acceleration of chromospheric outflow in the upper chromosphere. We also observe this decrease for the resonance line of Mg I λ2852 (not shown). Our previous radiative transfer modeling work based on Si I revealed that α Ori’s inner chromosphere oscillates nonradially, with simultaneous up- and downflows in Sept. 1998."[2]

X-rays

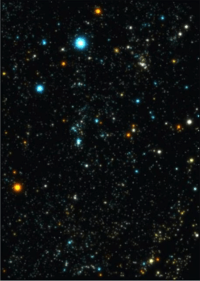

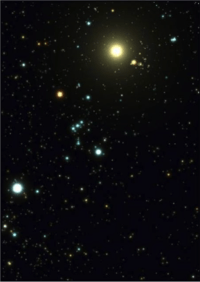

"This picture [on the right] shows the (X-ray) sky around midnight at the date [17 December 1994] of the Symposium above Munich, as seen with X-ray sensitive eyes."[3]

"From August 1990 to February 1991 the German X-ray satellite ROSAT performed the first all-sky survey in soft X-rays with an imaging telescope. We have synthesized the point sources found with a preliminary automatic source detection analysis of these data into a colour image which shows the X-ray sky around the Orion region (5228 objects in an area of approximately 50 deg x 75 deg) in a similar way as we perceive the optical sky."[3]

"For this image we have selected that part of the sky which culminated at midnight over Munich during the time of the TEXAS symposium. This is the region around Orion, probably the most beautiful and well-known area of the sky visible from mid-northern latitudes. According to the visual impression, we displayed it in a projection which compresses the areas close to the zenith."[3]

The image on the left is a match in the optical for the X-ray image on the right. Note that Betelgeuse in the optical image on the left is not visible in the ROSAT X-ray image on the right.

"Calculations based on a rather simple theory for quiet coronas (Grasberger and Henyey 1959), indicated that radiation from the chromosphere-corona of at least one of the nearby, bright supergiants (Deneb, Canopus, Betelgeuse, or Rigel) might be bright enough to be observed. [...] a variety of stellar sources can be observed."[4]

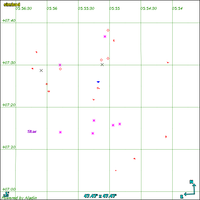

According to SIMBAD there is at least one X-ray source at or within 9 arcminutes of the coordinates of Betelgeuse. This source was found using "region(05 55 10.305 +07 24 25.43,9m) & otype='X'". It is 1RXS J055507.1+073007, which is a ROSAT designation. It is 5.74771' from Betelgeuse, which is probably just inside the bow shock.

In the interstellars section below the bow shocks and a linear dust bar are at or within 9 arcmin of Betelgeuse.

On the left is an Aladin sky map of the 27 known astronomical objects listed in SIMBAD as occurring within a 20' circle around Betelgeuse (red + with an arrow showing direction of movement).

Two X-ray (X) sources are present. Eight UV sources (pink *), eleven stars (small red circles), four infrared objects (red diamonds), and two submillimeter sources.

Comparing the locations of the two X-ray sources with their locations in relation to Betelgeuse and its bow shock, the closest is just inside the bow shock and the other is on the other side of the linear bar.

Ultraviolets

.jpg)

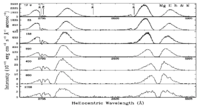

"The photo-montage made in ultraviolet light [on the right] shows the pulsating atmosphere of Betelgeuse. The star is scanned with the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph. Seven spectra are recorded through a small field of view shown by the rectangle at different positions on the disk, marked by the crosses. The thick yellow curves show the shape of a double-peaked emission line which emerges from Betelgeuse's chromosphere. The depression between the peaks is formed far out in this warmer envelope. The spectra in the top images of January and March '98 reveal that this outer region collapses since the left-hand peak of the emission line is everywhere stronger than the right. But the STIS scan in the lower left image of September '98 unveils how atmospheric gas begins to move up in the fifth scan position, where the right-hand peak exceeds the left. Here gas streams in opposite directions at the same time through the star's outer atmosphere. The spectral scan in the lower right image of March '99 shows that the expandingtrend proceeds and extends further across the chromosphere. The arrows in the images point North in the plane of the sky and should be aligned when comparing the location of surface details. Note that the mean intensity levels of the four images have been equalized to bring out these details. The top images are actually observed brighter than the lower ones. Note also that some spectral scans are taken a week apart from the images."[5]

"From early 1998 to spring 1999, the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) was used to scan Betelgeuse's disk four times and to record spectra from small slices cut across its surface."[6]

"We found the upper atmosphere or chromosphere warmer than the region below it and we observed that it also contracted and expanded during this period. But, most surprisingly, a scan in fall 1998 suggests streams of gas that are heading in opposite directions --with velocities of about 10,000 miles per hour."[6]

"Throughout the same period, the Faint Object Camera (FOC) was used to make new images of Betelgeuse's chromosphere in ultraviolet (UV) light. While the intensity of UV emitted by the chromosphere varied with the star's pulsation, brighter and rather subtle intensity patterns appeared at different locations on the stellar disk. Although an FOC observation [...] in 1995 revealed a bright spot-like area on Betelgeuse's surface, the new images -- with their improved resolution -- now also revealed that a bright 'arc-like' structure spanned a large portion of the disk in September 1998."[6]

"As astonishing as these images may be, they also show us that the precise locations of the brighter regions remain unresolved. Sharper and more frequent images obtained during one pulsation cycle are needed to pinpoint their physical origin."[6]

The "new images show that the upper atmosphere changes in a rather unordered manner just like the simultaneous up- and down-flows seen in the STIS spectra."[7]

"One out of a million stars in our galaxy is a supergiant and fewer yet are cool supergiants. Not only is Betelgeuse a cool supergiant, but it is also the seventh brightest star visible in the northern hemisphere, appearing in the shoulder of the constellation Orion at a distance of 425 light-years from Earth. Because its surface temperature can drop to below 3,000 K degrees, it shines reddish. Its atmosphere is like a big puffy cloud, ten million times less dense than our Sun; and, under such conditions, slight perturbations have dramatic effects on movements of its atmospheric gases."[6]

The "star is wrapped in an even bigger and less dense envelope of warmer gas. Its chromosphere extends up to 5,000 times the radius of our Sun, or out to Neptune's orbit, where the temperature can increase to about 5,000 K degrees. "[6]

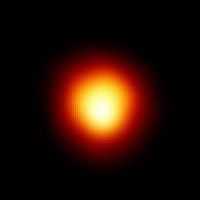

Opticals

"The yellow/red "image" or "photo" of Betelgeuse usually seen is actually not a picture of the red giant but rather a mathematically generated image based on the photograph. The photograph was actually of much lower resolution: The entire Betelgeuse image fit entirely within a 10x10 pixel area on the Hubble Space Telescopes Faint Object Camera. The actual images were oversampled by a factor of 5 with bicubic spline interpolation, then deconvolved."[8]

Polarized light

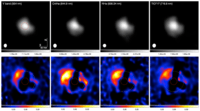

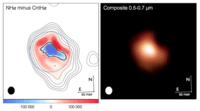

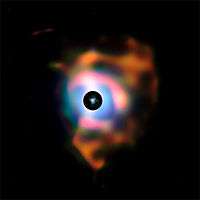

In the image on the right, "Asymmetric Betelgeuse and its environment [are] imaged in visible light (top) and polarized visible light (bottom). Each column is a different filter. The red dashed circle indicates Betelgeuse’s infrared photospheric radius. The light dashed circle is three times this."[9]

"As you can see in the images [on the right], Betelgeuse is not symmetric, and neither is its circumstellar material. The top row shows brightness in different visible-light filters while the bottom row shows degree of polarization (light colors are more polarized than dark)."[9]

"Most of the imaged polarized light is far from the star’s photosphere, and is probably polarized due to dust scattering. However, bits of this dust are close to the star, too! It’s well known that red supergiants like Betelgeuse lose significant amounts of mass. Mass loss seems to be connected to the huge convective cells inside supergiants, because they too are not spherically symmetric, but we don’t know precisely how. We do know the lost mass forms a circumstellar envelope around the star and and provides the material from which dust can form. It follows that if the dust was all far away or all close-in, that would tell us something about how it got there. Instead, at any single distance away from the star, we find different amounts of dust and gas in a range of different temperatures and densities."[9]

Visuals

"The red giant Betelgeuse, once so large it would reach out to Jupiter's orbit if placed in our own solar system, has shrunk by 15 percent over the past decade in a half, although it's just as bright as it's ever been."[10]

"We do not know why the star is shrinking. Considering all that we know about galaxies and the distant Universe, there are still lots of things we don't know about stars, including what happens as red giants near the ends of their lives."[11]

"Betelgeuse is beyond the death beam distance -- somewhere within 30 light years range -- where it could do ultimate damage to Earth. The explosion won't do the Earth any harm, as a star has to be relatively close -- on the order of 25 light years -- to do that. Betelgeuse is about 600 light years distant."[10]

The image on the right is a visual image using the Hubble Space Telescope with enhancements.

Oranges

This visual image of Betelgeuse probably with a Schmidt as part of the DSS shows its orange color.

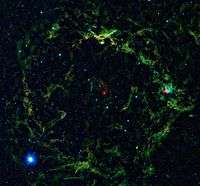

Reds

"Cradled in cosmic dust and glowing hydrogen, stellar nurseries in Orion the Hunter lie at the edge of a giant molecular cloud some 1,500 light-years away. Spanning nearly 25 degrees, this breath-taking vista stretches across the well-known constellation from head to toe (left to right). The Great Orion Nebula, the closest large star forming region, is right of center. To its left are the Horsehead Nebula, M78, and Orion's belt stars. Sliding your cursor over the picture will also find red giant Betelgeuse at the hunter's shoulder, bright blue Rigel at his foot, and the glowing Lambda Orionis (Meissa) nebula at the far left, near Orion's head. Of course, the Orion Nebula and bright stars are easy to see with the unaided eye, but dust clouds and emission from the extensive interstellar gas in this nebula-rich complex, are too faint and much harder to record. In this mosaic of broadband telescopic images, additional image data acquired with a narrow hydrogen alpha filter was used to bring out the pervasive tendrils of energized atomic hydrogen gas and the arc of the giant Barnard's Loop."[12]

Infrareds

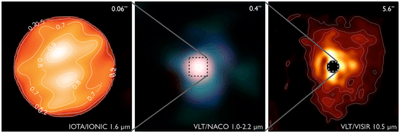

The image at right is "of the supergiant star Betelgeuse obtained with the NACO adaptive optics instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope. The use of NACO combined with a so-called “lucky imaging” technique, allows the astronomers to obtain the sharpest ever image of Betelgeuse, even with Earth’s turbulent, image-distorting atmosphere in the way. The resolution is as fine as 37 milliarcseconds, which is roughly the size of a tennis ball on the International Space Station (ISS), as seen from the ground. The image is based on data obtained in the near-infrared, through different filters. The field of view is about half an arcsecond wide, North is up, East is left."[14]

The image on the left shows the head and shoulders of Orion in the infrared. "In Greek mythology, Orion was a hunter whose vanity was so great that he angered the goddess Artemis. As his punishment, Artemis banished the hunter to the sky where he can be seen as the famous constellation Orion. In the constellation, Orion's head is represented by the star Lamdba Orionis (fuzzy red dot in middle). When viewed in infrared light, NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE, shows a giant nebula around Lambda Orionis, inflating Orion's head to huge proportions."[15]

"Lambda Orionis is a hot, massive star that is surrounded by several other hot, massive stars, all of which are creating radiation that excites a ring of dust, creating the "Lambda Orionis molecular ring." Also known as SH 2-264, the Lambda Orionis molecular ring is sometimes called the Meissa ring. In Arabic, the star Lambda Orionis is known as "Meissa" or "Al-Maisan," meaning "the shining one." The Meissa Ring is of interest to astronomers because it contains clusters of young stars and proto-stars, or forming stars, embedded within the clouds. With a diameter of approximately 130 light-years, the Lambda Orionis molecular ring is notable for being one of the largest star-forming regions WISE has seen. This is also the largest single image featured by WISE so far, with an area of the sky approximately 10 by 10 degrees in size, equivalent to a grid of 20 by 20 full moons. Nevertheless, at less than one percent of the whole sky's area, it is just a taste of WISE data."[15]

"The bright blue star in the lower left corner of the image is the star Betelgeuse, which represents one shoulder of the hunter Orion. The name Betelgeuse is actually a corruption of the original Arabic phrase "Yad al-Jauza'," meaning "hand of the giant one." Betelgeuse is well known for being a red supergiant star, yet in WISE's infrared view it appears blue, as do most stars in WISE images. This is because most stars, including Betelgeuse, put out more light in the shortest infrared wavelengths of light captured by WISE, and those shorter wavelengths are presented in WISE images as blue and cyan."[15]

"In visible light, Orion's other shoulder is clearly marked by the variable star Bellatrix. In infrared light, however, Bellatrix is a somewhat unremarkable cyan-colored star in the right side of the image. In Latin, Bellatrix means "female warrior," which is perhaps why the name was chosen for a female witch character in the popular Harry Potter books."[15]

"Also seen in this image are two dark nebulae, Barnard 30 and Barnard 35, which are parts of the Meissa ring that are so dense they block out visible light. Barnard 30 is the bright knob of gas and dust in the top center part of the image. Barnard 35 appears as a hook extending towards the center of the ring just above and to the right of the star Betelgeuse. The bright reddish object seen to in the middle right part of the image is the star HR 1763, which is surrounded by another star-forming region, LBN 867."[15]

"Color in this image represents specific wavelengths of infrared light. Blue and cyan represent 3.4- and 4.6-microns, primarily light emitted by hot stars. Green and red represent 12- and 22-micron light, which is mainly radiation from warm dust."[15]

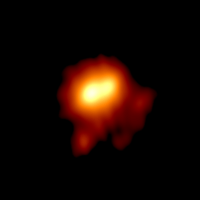

The second image down on the right is an interferometric image of the photosphere of Betelgeuse at 1.64 microns.

The second image down on the left is the unsmoothed infrared interferometry of the surface (photosphere) of Betelgeuse at 1.64 µm.

"The image reveals the presence of two giant bright spots, whose size is equivalent to the distance Earth-Sun : they cover a large fraction of the surface. It is a first strong and direct indication of the presence of phenomena of convection, transport of heat by the moving matter, in a star other than the Sun."[16]

"The analysis of the brightness of the spots shows a variation of 500 degrees compared to the average temperature of the star (3 600 Kelvins). The largest of the two structures has a dimension equivalent to the quarter of the star diametre (or one and a half the distance Earth-Sun). This marks a clear difference with the Sun where the cells of convection are much finer and reach hardly 1/20th of the solar radius (a few Earth radius). These characteristics are compatible with the idea of luminous spots produced by the convection."[16]

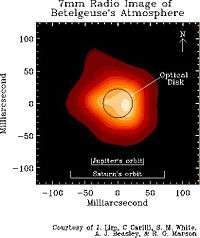

Radios

The image on the right is of Betelgeuse at 7 mm (45 Gz) radio waves.

"Close to the star, we find that the atmosphere has an irregular structure, and a temperature (3,450 +/- 850K) consistent with the photospheric temperature but much lower than that of gas in the same region probed by optical and ultraviolet observations. This cooler gas decreases steadily in temperature with radius, reaching 1,370 +/- 330K by seven stellar radii. The cool gas coexists with the hot chromospheric gas, but must be much more abundant as it dominates the radio emission."[17]

The asymmetric structure of Betelgeuse in radio waves shown in the image on the left is likely due to activity in the outer atmosphere of the star.

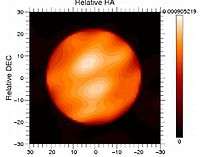

Hydrogens

"Two of the filters used to image Betelgeuse are sensitive to the familiar red hydrogen alpha spectral feature. Because one filter is broader than the other, subtracting the light in the narrow filter from the light seen with the broad filter yields a map of where hydrogen gas is emitting or absorbing light. It also turns out to be highly asymmetric. Most of the hydrogen emission is confined within a distance of three times Betelgeuse’s near-infrared radius. It’s a similar distance from the star as most of the polarized dust, but the spatial distributions are different."[9]

In the image on the right, "Left: A map of hydrogen emission (red) and absorption (blue) in the vicinity of Betelgeuse, with the same dashed lines [The red dashed circle indicates Betelgeuse’s infrared photospheric radius. The light dashed circle is three times this.] for reference. Right: Color composite of three of the filters from the first figure (the narrow hydrogen alpha filter is excluded)."[9]

"Betelgeuse’s asymmetries persist in both in dust and gas, with a major interface between the two located around three times the near-infrared stellar radius. These asymmetries agree with different types of past observations and also strongly point toward a connection between supergiant mass loss and vigorous convection."[9]

Ions

"[I]on lines of Fe II, Al II, and C II [have been observed] out to 1′′ in the upper chromosphere. [The set of graphs on the right] shows (scaled) emission lines of Fe II λ2716 (UV 62), Al II λ2669 (UV 1), and C II λ2327 (UV 1)."[6]

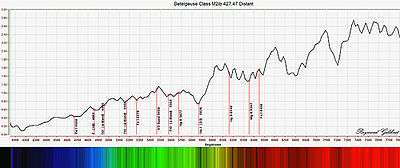

Spectroscopy

Above is a spectrum of Betelgeuse "taken with a SkyWatcher 200p / EQ5 / SynScan Tracking Star Analyser 100."[18]

The above spectrum of Betelgeuse has magnesium (Mg I) lines and strong titanium oxide (TiO2) bands. Its temperature is between 2,000 to 3,600 K.[18]

The spectrum of Betelgeuse on the right ranges from about 520.0 nm (blue-green) to about 640.0 nm (yellow) on the right end.

Stars

Def.

- any "small luminous dot appearing in the cloudless portion of the night sky, especially with a fixed location relative to other such dots"[19] or

- a "luminous celestial body, made up of plasma (particularly hydrogen and helium) and having a spherical shape"[19]

is called a star.

Chromospheres

The set of graphs on the right "shows the detailed profiles of the Mg II h & k lines observed up to 1000 mas. The emission line intensities decrease by a factor of ∼700 from chromospheric disk center (TP 0) to 1′′. These optically thick chromospheric lines show remarkable changes of their detailed shapes when scanning off-limb. The full width across both emission components at half intensity maximum decreases by ∼20%, while the broad and saturated central absorption core narrows by more than 50%. Beyond 600 mas the central core assumes a constant width which results from absorption contributions by the local interstellar medium (d∗≃132 pc). We observe a strong increase of the (relative) intensity of the long-wavelength emission component in both lines beyond 200 mas. It signals fast wind acceleration beyond this radius. Note that the short-wavelength emission components of the k and h lines are blended with chomospheric Mn I lines (decreasing the k- and increasing the h-component), but that become much weaker in the outer chromosphere."[2]

Interstellars

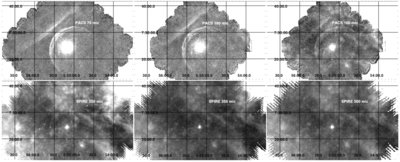

In the image above there are "Herschel [Photodetector Array Camera and Spectrometer] PACS and [Spectral and Photometric Imaging Receiver on board the Herschel satellite] SPIRE images of Betelgeuse. North is up, east to the left. The field-of-view (FOV) is ∼49′ ×29′."[20] The grid overlain is J2000.0 RA and Dec.

"For both instruments, the ‘scan map’ observing mode was used with medium (20′′/s) scan speed in the PACS 70, 100, and 160μm filter settings and 30′′/s for the SPIRE 250, 350, and 500 μm filters. To create a uniform cover- age, avoid striping artefacts, and increase redundancy, two ob- servations at orthogonal scan directions were concatenated. The PACS images were obtained on September 13, 2010 (OBSIDS 1342204435 and 1342204436) and on March 29, 2012 (OBSIDS 1342242656 and 1342242657), the SPIRE images on March 11, 2010 (OBSID 1342192099)."[20]

"The individual scan maps are plotted [in the image above] a multiple arc-like structure is detected at ∼6-7′ away from the central star, together with an enigmatic linear bar-like structure at ∼9′. [...] The inner radius of the closest arc is at 280′′ (as measured from the central target). The other most prominent arcs have an inner radius at 280′′, 310′′, 350′′ and 375′′. The brightest parts of the arcs are reasonably well fitted by concentric ellipses [...] The width of the arcs is typically ∼20′′. Clearly, substructures of the size of several arcseconds, probably related to density differences, are seen in the arcs. The arc-like structure is probably related to the [circumstellar matter-interstellar matter] CSM-ISM interaction phase, when the circumstellar material collides at a wind speed of ∼15 km/s with the ISM, creating a bow shock [...] The inner ridge of the linear bar is at 535′′ from the central star. The length is ∼1600′′. The width is ∼30′′ in the northern part; moving down towards the south-east, the bar widens and splits into two parts. The angle between the direction of space velocity [...] and the linear bar is ∼80°."[20]

"Multiple arcs are revealed around Betelgeuse, the nearest red supergiant star to Earth, in [the second image down on the right] from ESA’s Herschel space observatory. The star and its arc-shaped shields [or bow shock] could collide with an intriguing dusty ‘wall’ in 5000 years."[21]

The "far-infrared view from Herschel shows how the star’s winds are crashing against the surrounding interstellar medium, creating a bow shock as the star moves through space at speeds of around 30 km/s."[21]

"A series of broken, dusty arcs ahead of the star’s direction of motion testify to a turbulent history of mass loss."[21]

"Closer to the star itself, an inner envelope of material shows a pronounced asymmetric structure. Large convective cells in the star’s outer atmosphere have likely resulted in localised, clumpy ejections of dusty debris at different stages in the past."[21]

"An intriguing linear structure is also seen further away from the star, beyond the dusty arcs. While some earlier theories proposed that this bar was a result of material ejected during a previous stage of stellar evolution, analysis of the new image suggests that it is either a linear filament linked to the Galaxy’s magnetic field, or the edge of a nearby interstellar cloud that is being illuminated by Betelgeuse."[21]

"The infrared Herschel images of the environment around Betelgeuse [show] the occurrence of multiple arcs at 6-7 arcmin from the central target and the presence of a linear bar at 9 arcmin."[20]

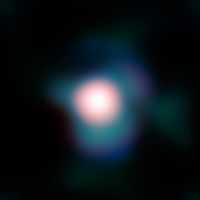

Nebulas

"This picture [on the right] of the dramatic nebula around the bright red supergiant star Betelgeuse was created from images taken with the VISIR infrared camera on ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT). This structure, resembling flames emanating from the star, forms because the behemoth is shedding its material into space. The earlier NACO observations of the plumes are reproduced in the central disc. The small red circle in the middle has a diameter about four and half times that of the Earth’s orbit and represents the location of Betelgeuse’s visible surface. The black disc corresponds to a very bright part of the image that was masked to allow the fainter nebula to be seen."[22]

"The VLT image shows the surrounding nebula, which is much bigger than the supergiant itself, stretching 37 billion miles (60 billion kilometers) away from the star’s surface – about 400 times the distance of Earth from the Sun."[23]

In theory, "Red supergiants like Betelgeuse represent one of the last stages in the life of a massive star. In this short-lived phase, the star increases in size and expels material into space at a tremendous rate — it sheds immense quantities of material (about the mass of the Sun) in just 10,000 years. [...] the plumes seen close to the star are probably connected to structures in the outer nebula now imaged in the infrared with VISIR. The nebula cannot be seen in visible light, as the very bright Betelgeuse completely outshines it. The irregular, asymmetric shape of the material indicates that the star did not eject its material in a symmetric way. The bubbles of stellar material and the giant plumes they originate may be responsible for the clumpy look of the nebula."[23]

"The small red circle in the middle has a diameter about 4.5 times that of Earth’s orbit and represents the location of Betelgeuse’s visible surface. The black disk corresponds to a bright part of the image that was masked to allow the fainter nebula to be seen. The VISIR images were taken through infrared filters sensitive to radiation of different wavelengths, with blue corresponding to shorter wavelengths and red to longer. The field of view is 5.63 by 5.63 arcseconds."[23]

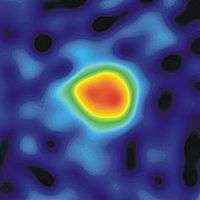

Bright nebulas

"The image [on the right] shows Betelgeuse’s atmosphere extending out to five times the size of the visual surface of the star. It also reveals two hot spots within the outer atmosphere and a faint arc of cool gas even farther out beyond the radio surface of the star. The arc of cool gas extends about as far away as Pluto is from our Sun."[24]

"The hot spots have a temperature of about 6,740 to 8,540 degrees Fahrenheit [4000 to 5000 K], which is much higher than the average temperature of the radio surface of the star and even higher than the visual surface."[24]

The photosphere of the Sun is at 5778 K.

"This is the first image showing hot spots this far away from the center of the star."[24]

"The new image, taken by the e-MERLIN radio telescope array operated from the Jodrell Bank Observatory in Cheshire, also shows regions of surprisingly hot gas in the star’s outer atmosphere and a cooler arc of gas weighing almost as much as the Earth."[24]

Red supergiants

"Red supergiants (RSGs) are supergiant stars (luminosity class I) of spectral type K or M. They are the largest stars in the universe in terms of volume, although they are not the most massive. Betelgeuse and Antares are the best known examples of a red supergiant. ... These stars have very cool surface temperatures (3500–4500 K), and enormous radii. The five largest known red supergiants in the Galaxy are VY Canis Majoris, VV Cephei A, V354 Cephei, RW Cephei and KW Sagittarii, which all have radii about 1500 times that of the [S]un (about 7 astronomical units, or 7 times as far as the Earth is from the [S]un). The radius of most red giants is between 200 and 800 times that of the [S]un. ... Absolute luminosities may reach -10 magnitude compared to +5 for our [S]un."[25]

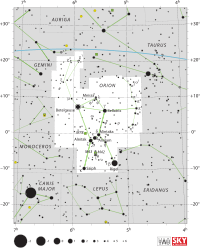

Orion

At right is the IAU sky chart for Orion with notable sources including Betelgeuse indicated.

On the left is a full color image of the constellation of Orion with an arrow pointing to Betelgeuse.

Classical history

The classical history period dates from around 2,000 to 1,000 b2k.

"Around 150 AD, the Hellenistic astronomer Claudius Ptolemy described Sirius as reddish, along with five other stars, Betelgeuse, Antares, Aldebaran, Arcturus and Pollux, all of which are clearly of orange or red hue.[26]"[27]

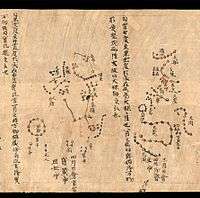

A segment of the Dunhuang star map from around 700 AD (1,300 b2k) on the right contains the constellation of Orion to the left. Betelgeuse is the star at the top of Orion.

Recent history

_(14778558682).jpg)

The recent history period dates from around 1,000 b2k to present.

On the upper right is a celestial map of the constellations near or around Taurus, including Orion with Betelgeuse the star in Orion's right shoulder. This image is from 1690 (310 b2k).

On the lower right is a celestial map of the stars and constellations near to Betelgeuse from 1898 (102 b2k).

"Among colored stars, single and double, a few maybe mentioned by name as examples. Sirius, as already observed, is a brilliant white sun; and brilliant white also are Vega, Altair, Regulus, Spica, and many others. Capella, Procyon, the Pole star, and our own sun, are examples of yellow stars. Aldebaran, Betelgeuse, and Pollux, are ruby-red. Antares is a red star."[28]

Research

Hypothesis:

- Betelgeuse has a low-temperature photosphere relative to the Sun because the interstellar electron influx is much less intense.

- Betelgeuse is a young star being compressed by interstellar electron influx.

Control groups

The findings demonstrate a statistically systematic change from the status quo or the control group.

“In the design of experiments, treatments [or special properties or characteristics] are applied to [or observed in] experimental units in the treatment group(s).[29] In comparative experiments, members of the complementary group, the control group, receive either no treatment or a standard treatment.[30]"[31]

Proof of concept

Def. a “short and/or incomplete realization of a certain method or idea to demonstrate its feasibility"[32] is called a proof of concept.

Def. evidence that demonstrates that a concept is possible is called proof of concept.

The proof-of-concept structure consists of

- background,

- procedures,

- findings, and

- interpretation.[33]

See also

References

- ↑ Yaël Nazé, and Xiao Che, Nick L.J. Cox, José H. Groh, Martin Guerrero, Pierre Kervella, Chien-De Lee, Mikako Matsuura, Sally Oey, Guy S. Stringfellow, Stephanie Wachter (October 2012). T. Montmerle. ed. SpS5 - III. Matter ejection and feedback, In: Highlights of Astronomy. 16. International Astronomical Union. pp. 429-38. doi:10.1017/S174392131401179X. http://arxiv.org/pdf/1210.3986.pdf. Retrieved 2015-12-26.

- 1 2 3 4 A. Lobel, J. Aufdenberg, A. K. Dupree, R. L. Kurucz, R. P. Stefanik, and G. Torres (January 2004). A.K. Dupree and A.O. Benz. ed. Spatially Resolved STIS Spectroscopy of Betelgeuse’s Outer Atmosphere, In: Stars as Suns: Activity, Evolution and Planets. 219. San Francisco, CA USA: Astronomical Society of the Pacific. pp. 641-5. Bibcode: 2004IAUS..219..641L. http://arxiv.org/pdf/astro-ph/0312076v1. Retrieved 2015-12-28.

- 1 2 3 Konrad Dennerl and Wolfgang Voges (17 December 1994). "The ROSAT X-Ray Sky Around Orion". Munich, Germany: Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

- ↑ Philip C. Fisher and Arthur J. Meyerott (January 1964). "Stellar X-ray Emission". The Astrophysical Journal 136 (01): 123-42. doi:10.1086/147742. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1964ApJ...139..123F. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ David Aguilar and Christine Pulliam (13 January 2000). "LIKE A HUMAN HEART: BETELGEUSE'S CHROMOSPHERE BEATS ASYMMETRICALLY". 60 GARDEN STREET, CAMBRIDGE, MA 02138 USA: Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Retrieved 2015-12-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Alex Lobel, Andrea Dupree, and Roland Gilliland (13 January 2000). "LIKE A HUMAN HEART: BETELGEUSE'S CHROMOSPHERE BEATS ASYMMETRICALLY". 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 USA: Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Retrieved 2015-12-28.

- ↑ Andrea Dupree (13 January 2000). "LIKE A HUMAN HEART: BETELGEUSE'S CHROMOSPHERE BEATS ASYMMETRICALLY". 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 USA: Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Retrieved 2015-12-28.

- 1 2 Ronald L. Gilliland, Andrea K. Dupree (May 1996). "First Image of the Surface of a Star with the Hubble Space Telescope" (PDF). Astrophysical Journal Letters 463 (1): L29-32. doi:10.1086/310043. http://iopscience.iop.org/1538-4357/463/1/L29/pdf/5023.pdf. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Meredith Rawls (24 November 2015). "Zooming in on Betelgeuse". Astrobites. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- 1 2 Richard Mushotzky (08 October 2015). "Image of the Day: Is the Milky Way's Red Giant Betelgeuse the Next Nearby Supernova?". Daily Galaxy. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

- ↑ Edward Wishnow (08 October 2015). "Image of the Day: Is the Milky Way's Red Giant Betelgeuse the Next Nearby Supernova?". Daily Galaxy. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

- ↑ Robert Nemiroff & Jerry Bonnell (23 October 2010). "Orion: Head to Toe". Washington, DC USA: NASA. Retrieved 2015-12-28.

- ↑ Robert Nemiroff (MTU) & Jerry Bonnell (USRA) (5 August 2009). "Betelgeuse Resolved". Today's Astronomy Picture of the Day. http://antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov/apod/ap090805.html. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ↑ P. Kervella (July 29, 2009). "A close look at Betelgeuse". Santiago, Chile: European Southern Observatory. Retrieved 2012-07-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tony Greicius (18 April 2011). "Orion's Big Head Revealed in Infrared". Washington, DC USA: NASA. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

- 1 2 Xavier Haubois and Guy Perrin (1 January 2010). "Unprecedented details on the surface of the Betelgeuse star". Paris, France: Observatoire de Paris, LESIA, et CNRS. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

- ↑ Jeremy Lim, Chris L. Carilli, Stephen M. White, Anthony J. Beasley, and Ralph G. Marson (April 1998). "Large convection cells as the source of Betelgeuse's extended atmosphere". Nature 392 (676): 575-7. doi:10.1038/33352. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/nph-bib_query?bibcode=1998Natur.392..575L. Retrieved 2015-12-28.

- 1 2 Raymond Gilchrist (23 January 2013). "Betelgeuse Graph and Spectrum". Flickr.com. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- 1 2 "star, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. July 6, 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- 1 2 3 4 L. Decin, N.L.J. Cox, P. Royer, A.J. Van Marle, B. Vandenbussche, D. Ladjal, F. Kerschbaum, R. Ottensamer, M.J. Barlow, J.A.D.L. Blommaert, H.L. Gomez, M.A.T. Groenewegen, T. Lim, B.M. Swinyard, C. Waelkens, and A.G.G.M. Tielens (December 2012). "The enigmatic nature of the circumstellar envelope and bow shock surrounding Betelgeuse as revealed by Herschel. I. Evidence of clumps, multiple arcs, and a linear bar-like structure". Astronomy and Astrophysics 548 (A113): 24. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219792. http://arxiv.org/pdf/1212.4870v1.pdf. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Leen Decin (22 January 2013). "Betelgeuse Braces for a Collision". European Space Agency. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

- ↑ P. Kervella (23 June 2011). "The flames of Betelgeuse". Garching, Germany: European Southern Observatory. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- 1 2 3 P. Kervella (23 June 2011). "The flames of Betelgeuse". Garching, Germany: European Southern Observatory. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- 1 2 3 4 Anita Richards (24 April 2013). "New Image Of Betelgeuse Reveals Hot Spots". Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ "Red supergiant, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. June 6, 2012. Retrieved 2012-06-09.

- ↑ J.B. Holberg (2007). Sirius: Brightest Diamond in the Night Sky. Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing. ISBN 0-387-48941-X.

- ↑ "Sirius, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. July 31, 2012. Retrieved 2012-08-14.

- ↑ Agnes Giberne (1898). The story of the sun, moon, and stars. Cincinnati, Ohio USA: Cincinnati National book company. pp. 430. https://archive.org/details/storyofsunmoonst00gibe. Retrieved 2015-12-28.

- ↑ Klaus Hinkelmann, Oscar Kempthorne (2008). Design and Analysis of Experiments, Volume I: Introduction to Experimental Design (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-72756-9. http://books.google.com/?id=T3wWj2kVYZgC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ R. A. Bailey (2008). Design of comparative experiments. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68357-9. http://www.cambridge.org/uk/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521683579.

- ↑ "Treatment and control groups, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. May 18, 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-31.

- ↑ "proof of concept, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. November 10, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ↑ Ginger Lehrman and Ian B Hogue, Sarah Palmer, Cheryl Jennings, Celsa A Spina, Ann Wiegand, Alan L Landay, Robert W Coombs, Douglas D Richman, John W Mellors, John M Coffin, Ronald J Bosch, David M Margolis (August 13, 2005). "Depletion of latent HIV-1 infection in vivo: a proof-of-concept study". Lancet 366 (9485): 549-55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67098-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1894952/. Retrieved 2012-05-09.

External links

- International Astronomical Union

- The SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System

- Scirus for scientific information only advanced search

- SDSS Quick Look tool: SkyServer

- SIMBAD Astronomical Database

- SIMBAD Web interface, Harvard alternate

- Universal coordinate converter

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![]() This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

| |

Development status: this resource is experimental in nature. |

| |

Educational level: this is a research resource. |

| |

Resource type: this resource is an article. |

| |

Resource type: this resource contains a lecture or lecture notes. |

| |

Subject classification: this is an astronomy resource. |