Motivation and emotion/Book/2011/Shame

< Motivation and emotion < Book < 2011

Avoiding the shame game: Understanding and managing feelings of shame

|

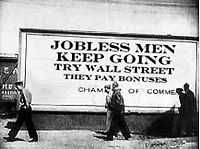

Introduction Pointing the finger of shame When the concept of shame crops up in ordinary conversation, it tends to be as an important quality we see lacking in others rather than ourselves. The thief who robs the pensioner "has no shame"; someone who steps over perceived boundaries of public propriety may be labelled "shameless"; protesters may be seen pointing an accusing finger of shame at the Government which they believe has failed them; or there may be talk of "naming and shaming" those who have covered up some offence against a moral code. These examples suggest that shame plays a regulatory role in social or moral terms. However, they do not provide a full account of what it means to actually experience shame. Experiences of such a powerful negative emotion as shame can be very challenging to recall and even more difficult to disclose. When shame plays a major role in daily lived experience, the situation can be even more painful. This chapter is intended to help you understand how shame works and explore ways to manage this intense emotion effectively. ScenariosThese three scenarios are intended to help you to think about what it means to experience shame.

Now that you have read their stories...

What is shame? Anonymous grafitti accusations Shame is considered to be part of a set of self-conscious emotions which also includes guilt, embarrassment, social anxiety and pride (Leary, 2007). This suite of emotions are grouped together because they all involve making some sort of evaluation of ourselves based on how we expect real or imagined others are judging us (Leary). It is not classed as a core emotion: we are not born with the ability to make these types of judgements (Tangney, Stuewig,& Mashek, 2007). These emotions therefore rely on our development of objective self-awareness, an ability to make inferences about the views of others, as well as internalised standards against which we evaluate ourselves (Leary; Lewis, 1995, p. 91; Tangney et al., 2007). With shame, an intensely painful emotion, the result of this evaluation is the feeling that our entire self is defective (Tangney et al., 2007). This may be referred to as "internal shame" (Brown, Linehan, Comtois, Murray, & Chapman, 2009). Shame also exposes us as flawed and vulnerable to others who we believe react to this imperfect self with contempt and disgust (Lewis, 1995). This "external shame" drives the desire to conceal the flawed aspects of ourselves from others to avoid potential rejection (Brown, et al., 2009). It is also possible to experience shame vicariously through the actions of others closely associated with us, such as if a family member or friend were found to be a paedophile (Leary, 2007).  Going back to our scenarios

The shamed body and brain: Physiological changes associated with shame

Red-faced The experience of shame is associated with changes to emotional expression, physical reactions, body chemistry, and brain activity (Beer, Heerey, Keltner, Scabini & Knight, 2003; Leary, 2007; Lewis, 1971; Tangney et al., 2007; Tracy, Robins & Schriber, 2009). The most obvious changes relate to emotional expression and some physical reactions:

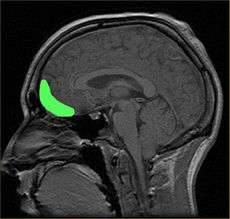

The changes that occur within the body are more subtle. Tangney and colleague's (2007) comprehensive review points to emerging evidence that shame is associated with increased cortisol levels, heightened immune response, and higher levels of cardiovascular reactivity (increased heart rate and blood pressure). Cortisol helps the body access extra energy stores by raising blood sugar levels (Dickerson et al., 2004). The heightened immune response involves proinflammatory cytokines which are associated with "sickness behaviours" (Dickerson et al.; Slavich, O'Donovan, Epel & Kemeny, 2010). In other words, like someone with a bad cold, the shamed person may feel lethargic, with a decreased desire for physical exertion or social interaction (Dickerson et al.; Slavich et al., 2010). These changes may help the body prepare to respond to the shaming situation, providing additional motivation needed to withdraw from a potentially damaging social threat (Dickerson et.al; Slavich et al.). Shame is a particularly strong trigger of this stress response (Dickerson et al.). The chapter on Handling Stress covers the neurological aspects of stress in more detail.  Approximate location of orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) Within the brain, there is some support for the role of the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) in producing self-conscious emotions, such as shame (Beer, et al., 2003; Leary, 2007; Sturm, Ascher, Miller, & Levenson, 2008). People with damage to the OFC have shown impairments in both the ability to appropriately express self-conscious emotions, such as shame, and in their social behaviour (Beer et al.). In Beer and colleagues' (2003) study, participants with OFC damage were more likely to overshare intimate information on a disclosure task, for example, telling about cheating on their partner, whereas other participants gave more guarded answers, such as being embarrassed when they did not understand a punchline. Those with OFC damage were also less likely to recognise self-conscious emotions on a recognition test than participants without any damage, although there was no difference between the groups in recognising other emotions (Beer et al.). This inability to correctly detect others' emotional responses suggests people with OFC damage may be missing important signals that their behaviour is inappropriate, such as others' embarrassment (Beer et al.). However, since others do not have to be real or physically present for a person to experience shame or the other self-conscious emotions, this suggests damage impairs the ability to correctly infer others' reactions to behaviour (Beer et al.). Shame, guilt and embarrassment - Spot the differencesAlthough shame, guilt and embarrassment are all negative self-conscious emotions, there are important differences between them (Keltner & Busnell, 1996). Shame can be distinguished from guilt on a number of dimensions, as the table below shows (Kim, Thibodeau & Jorgenson, 2011). A key difference is that shame arises from a person's evaluation of their whole self, rather than a specific action (Tangey et al. 2007; Leary, 2007). If I feel like a bad person, that is shame; if I feel bad about something I did, that is guilt (Leary, 2007).

Sometimes the differences between embarrassment and shame are not described very clearly or even recognised (Keltner & Busnell, 1996). While both shame and embarrassment seem concerned with the judgement of others, there is a distinct body language of embarrassment(Tracy et al., 2009). Although the head is turned down in embarrassment, as it would be for shame, it is tilted sideways and the person has a small sheepish smile which is sometimes combined with a hand touching the face (Tracey et al.). Embarrassment is also recognised as a less intense emotion than shame and one of shorter duration (Tangney & Dearing, 2004; Leary, 2007). The types of situations in which embarrassment occurs tend to be merely socially awkward, for example, tripping in public, minor loss of bodily control or otherwise becoming conspicuous (Leary; Tangney et al., 2007).  Going back to our scenarios

Why we experience shame: Theoretical perspectivesEvolutionary theory The opposite of shame - pride - is the reward that comes with socially valued behaviour. The basic evolutionary perspective is that emotions have an adaptive purpose - they evolved to help us survive (Dickerson et al., 2004). Self-conscious emotions are concerned with our social survival (Beer, et al., 2003; Dickerson et al., 2004). Negative self-conscious emotions including shame, punish socially unacceptable behaviour while a positive self-conscious emotion, such as pride, act as a reward for socially valued behaviour (Beer, et al.; Dickerson et al.). However, the adaptive qualities of shame go beyond trying to get us to avoid socially unacceptable behaviour by making us feel bad. Evolutionary theorists argue that experiencing shame actually helps us to avoid the consequences of acting inappropriately (Beer et al., 2003; Dickerson et al., 2004). Just as fear can help us prepare to face a physical danger by inducing a flight or fight reaction, shame literally shapes an adaptive response to social threats (Beer et al; Dickerson et al.). The physical manifestation of shame is the humble posture required to appease those who have been offended by the bad behaviour (Beer et al.; Dickerson et al.). This posture has been compared to appeasement behaviours in other species, such as primates, which signal the desire to avoid conflict with other group members (Beers et al.; Dickerson, et al.; Leary, 2007). Shamed people often express the desire to disappear, hide or escape from the shaming situation (Dickerson et al.; Tangney & Dearing, 2004; Tangney et al., 2007). The submissive posture coupled with the desire to withdraw is meant to reduce social tension and decrease the likelihood that the offended person will attack (Dickerson et al.). Cognitive Attributional TheoryCognitive Attributional Theory (CAT) regards shame as the outcome of three sets of cognitive activities: standards, rules and goals; the evaluation of success or failure against these goals; and attribution to self (Lewis, 1995, pp. 64-83). The standards vary between cultures, different social and age groups and within individuals (Lewis, p. 65). Children's socialisation experiences play a large part in which standards they internalise and the type of attributions they make about themselves (Lewis, p. 109).  Developing an understanding of self takes time. By around age three, children have normally internalised their own set of standards and may feel uncomfortable or upset if they fail to live up to them (Lewis, p. 67). They have also developed self-awareness by this age, an important step in making attributions to self (Lewis, p. 48). These attributions are about whether the success or failure is global, involving the whole self, or merely specific, involving a single action (Lewis, p. 72-73). Whether the child blames themselves (internal blame) or others (external blame) is also part of CAT, with younger children more likely to opt for internal blame (Lewis, pp. 100-102). The table below maps out the different emotional outcomes depending on attributional style, success or failure. Shame occupies the quadrant which involves failure attributed globally to the self.

CAT has been so highly influential in the study of shame and self-conscious emotions, that it is difficult to define these emotions without reference to it. CAT also forms the basis for key instruments, such as the Test of Self-Conscious Affect (TOSCA) which distinguishes between shame and guilt (Luyten, Fontaine, & Corveleyn, 2002; Tangney & Dearing, 2004). The TOSCA itself has been criticised for downplaying the maladaptive aspects of guilt and the adaptive aspects of shame (Luyten et al., 2002). However, it is difficult to fault the TOSCA or its theoretical underpinnings, given the growing evidence base supporting the distinctions it makes (Dearing, Stuewig, & Tangney, 2005; Kim et al., 2011; Leary, 2007; Highfield, Markham, Skinner & Neal, 2010).  Going back to our scenarios

How to deal with shameDoes experiencing shame have any benefits?

Shame can play an important role in helping us manage interpersonal relationships, ensuring that we moderate our behaviour in ways that acknowledge that we act within a broader social context (Beer, et al., 2003; Dickerson et al., 2004). Certainly, those whose ability to feel shame or other self-conscious emotions is impaired or disrupted often have difficulties with basic social functioning many of us take for granted (Beer et al.). The physiological reactions associated with shame may sometimes help us avoid conflict or minimise the impact of hostile social situations (Beer et al.). Shame may have helped humans survive in evolutionary terms. However, shame is effectively a short term strategy in terms of interpersonal relationships. The body of research evidence suggests that guilt rather than shame tends to be the more morally effective emotion (Tangney et al., 2007). Unlike shame, guilt is more likely to encourage patterns of behaviour which involve empathy for others, accepting responsibility for mistakes, saying sorry and making amends (Tangney et al.). Indeed, some researchers, assert that shame has few if any benefits, getting in the way of our feelings of worth and our ability to connect with others and belong (Brown, 2006). Although shame itself is not a diagnosis, it can be a problematic emotion for many individuals today, with substantial empirical evidence linking shame to a range of psychological and physical health issues (Brown, et al., 2009; Highfield, Markham, Skinner & Neal, 2009; Kim, et al., 2011; Tangney,2007; Tangney, et al., 2004; Tracy & Robins, 2004). These include:

Chances are either you or someone you know has struggled with feelings of shame at some point in their life. Sometimes the shame is obscured by a more obvious emotion, like anger. Shame and anger are closely connected, with recent research confirming this applies across all age groups (Lewis, 1971; Tangney, et al., 2007; Tangney & Dearing,2004). In feeling shamed, the whole self is globally judged as "bad" by real or perceived others (Tangey & Dearing). As a result, the shamed person may feel unfairly judged, in that he or she has no control over their entire being and therefore no way of remedying the situation (Tangney, et al.). In these circumstances, anger may be directed outwards towards those others seen to be doing the judging (Tangney & Dearing). This can have devastating effects within relationships, with some couples becoming locked into a mutually destructive pattern of behaviour called a shame-rage spiral (Lewis, 1971; Tangney et al.). Sometimes a major psychological issue, such as depression can obscure the issue of shame. There is also substantial evidence based on over 20 years of studies and over 20,000 research participants which connects shame with depression (Kim et al., 2011). Shame alone was significantly correlated with depression (r = .36) whereas guilt alone was not (Kim et al.). These results overturn accepted thinking about the respective roles of shame and guilt in depression (Kim et al.). Various explanations for the link between shame and depression have been offered including decreased social support, social conflict, self-focussed rumination and unhelpful attribution patterns (Kim et al.). However, there is not enough evidence as yet to clearly support any single theory (Kim et al.). How do we cope with shame when it is hurting us or the people we care about?

There are lots of ways to get help if you or a loved one are dealing with difficult and shameful feelings. Here are just a few:

SummaryShame may have been an evolutionary necessity but if it continues to strike at the core of who you are, you can get help to learn to manage shame and:

Quiz

See also

ReferencesBeer, J. S., Heerey, E. A., Keltner, D., Scabini, D., & Knight, R. T. (2003). The regulatory function of self-conscious emotion: Insights from patients with orbitofrontal damage. Journal of personality and social psychology, 85, 594-604. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.594 Brown, B. (2006). Shame resilience theory: A grounded theory study on women and shame. Families in Society, 87, 43-43-52. Brown, M. Z., Linehan, M. M., Comtois, K. A., Murray, A., & Chapman, A. L. (2009). Shame as a prospective predictor of self-inflicted injury in borderline personality disorder: A multi-modal analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 815-822. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.06.008 Dearing, R. L., Stuewig, J., & Tangney, J. P. (2005). On the importance of distinguishing shame from guilt: Relations to problematic alcohol and drug use. Addictive Behaviors, 30, 1392-1404. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.02.002 Dickerson, S. S., Gruenewald, T. L., & Kemeny, M. E. (2004). When the social self is threatened: Shame, physiology, and health. Journal of Personality, 72, 1191-1216. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00295.x Gilbert, P. (2009). Introducing compassion-focussed therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 15, 199–208 doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.107.005264 Gilbert, P. & Procter, S. (2006). Compassionate Mind Training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 13, 353-379. doi: 10.1002/cpp.507 Highfield, J., Markham, D., Skinner, M., & Neal, A. (2010). An investigation into the experience of self-conscious emotions in individuals with bipolar disorder, unipolar depression and non-psychiatric controls. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 17, 395-405. Keltner, D., & Buswell, B. N. (1996). Evidence for the distinctness of embarrassment, shame, and guilt: A study of recalled antecedents and facial expressions of emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 10, 155-171. Kim, S., Thibodeau, R., & Jorgensen, R. S. (2011). Shame, guilt, and depressive symptoms: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 68-96. doi: 10.1037/a0021466 Leary, M. R. (2007). Motivational and emotional aspects of the self. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 317-344. doi: doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085658 Lewis, H. B. (1971). Shame and guilt in neurosis. Psychoanalytic Review, 58, 419-438 Lewis, M. (1995). Shame: the exposed self. New York: The Free Press. Luyten, P., Fontaine, J. R. J., & Corveleyn, J. (2002). Does the Test of Self-Conscious Affect (TOSCA) measure maladaptive aspects of guilt and adaptive aspects of shame? An empirical investigation. Personality and Individual Differences, 33, 1373-1387. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(02)00197-6 Sturm, V. E., Ascher, E. A., Miller, B. L., & Levenson, R. W. (2008). Diminished self-conscious emotional responding in frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients. Emotion, 8, 861-869. doi: 10.1037/a0013765 Tangney, J. P. & Dearing, R. L., (2004). Shame and Guilt. New York: The Guildford Press. Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007). Moral Emotions and Moral Behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 345-372. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070145 Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2004). Putting the self into self-conscious emotions: A theoretical model. Psychological Inquiry, 15, 103-125. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1502_01 Tracy, J. L., Robins, R. W., & Schriber, R. A. (2009). Development of a FACS-verified set of basic and self-conscious emotion expressions. Emotion, 9, 554-559. doi: 10.1037/a0015766 External links | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||