Rocks/Rocky objects/Asteroids

< Rocks < Rocky objects

Asteroids are small rocky objects orbiting the Sun.

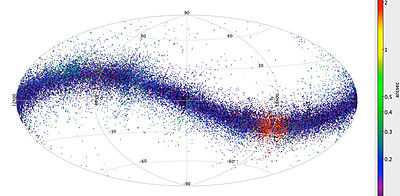

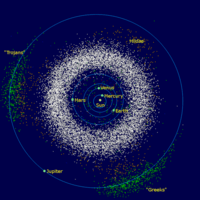

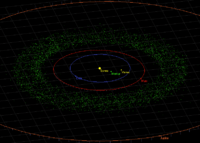

Large numbers of asteroids as indicated in the image from Gaia at the top ranging in size from Ceres to dust particles are found in the asteroid belt especially between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter.

Rocks

Petrology is a branch of geology that studies rocks, and the conditions in which rocks form. Lithology focuses on macroscopic hand-sample or outcrop-scale description of rocks, as in the image on the right, while petrography deals with microscopic details. Petrology benefits from mineralogy, optical mineralogy, geochemistry, and geophysics. Three branches of petrology focus on the three major rock types: igneous petrology, metamorphic petrology, and sedimentary petrology.

Rocky objects

A rocky object is any object, including astronomical objects, composed of one or more types of rocks.

A division of astronomical objects between rocky objects, liquid objects, gaseous objects (including gas giants and stars), and plasma objects may be natural and informative.

This division allows moons like Io to be viewed as rocky objects like Earth, rather than as a satellite around Jupiter.

The astronomy of such objects may be called rocky-object astronomy.

The object imaged on the right is a rock, a diabase with an aphanitic groundmass and plagioclase phenocrysts. It is also a rocky object in part because it is no longer connected to the rest of its original rock. From its rounded appearance it was probably found in a stream bed.

Theoretical asteroids

Def. a "naturally occurring solid object, which is smaller than a planet and is not a comet, that orbits a star"[1] is called an asteroid.

Usage notes

"The term "asteroid" has never been precisely defined. It was coined for objects which looked like stars in a telescope but moved like planets. These were known from the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, and were later found co-orbiting with Jupiter (Trojan asteroids) and within the orbit of Mars. They were naturally distinguished from comets, which did not look at all starlike. Starting in the 1970s, small non-cometary bodies were found outside the orbit of Jupiter, and usage became divided as to whether to call these "asteroids" as well. Some astronomers restrict the term "asteroid" to rocky or rocky-icy bodies with orbits up to Jupiter. They may retain the term planetoid for all small bodies, and thus tend to use it for icy or rocky-icy bodies beyond Jupiter, or may use dedicated words such as centaurs, Kuiper belt objects, transneptunian objects, etc. for the latter. Other astronomers use "asteroid" for all non-cometary bodies smaller than a planet, even large ones such as Sedna and (occasionally) Pluto. However, the distinction between asteroid and comet is an artificial one; many outer "asteroids" would become comets if they ventured nearer the Sun. The official terminology since 2006 has been small Solar System body for any body that orbits the Sun directly and whose shape is not dominated by gravity."[1]

Entities

"Asteroids in particularly large classes tend to be broken into subgroups with the first letter denoting the dominant group and the succeeding letters denoting less prominent spectral affinities or subgroups."[2]

"From the dominant group, the asteroids evolve to intersect the Earth's orbit on a median time scale of about 60 Myr."[3]

A asteroids

Spectra "of several related asteroid classes (types A, R, and V) were also analyzed for comparison to various S-subtypes."[4]

"Observing 246 Asporina and 289 Nenetta, [6] were the first to identify A-type asteroids as nearly pure olivine assemblages based on their spectral character- istics. These asteroids display a single broad absorp- tion feature centered at 1.06 μm (Band I) without any significant pyroxene feature at ~2.0 μm (Band II)."[5]

Only "a handful of A-type objects were discovered during the taxonomic surveys, assuming that all A-type asteroids are olivine-rich. The study of A-type asteroids may help solve the “missing mantle problem” in the asteroid belt."[5]

Blue asteroids

"Spectrally blue (B-type) asteroids are rare, with the second discovered asteroid, Pallas, being the largest and most famous example."[6]

"[T]he negative optical spectral slope of some B-type asteroids is due to the presence of a broad absorption band centered near 1.0 μm. The 1 μm band can be matched in position and shape using magnetite (Fe3O4), which is an important indicator of past aqueous alteration in the parent body. ... Observations of B-type asteroid (335) Roberta in the 3 μm region reveal an absorption feature centered at 2.9 μm, which is consistent with the absorption due to phyllosilicates (another hydration product) observed in CI chondrites. ... at least some B-type asteroids are likely to have incorporated significant amounts of water ice and to have experienced intensive aqueous alteration."[6]

"The [Sloan Digital Sky Survey] SDSS “blue” asteroids are related to the C-type (carbonaceous) asteroids, but not all of them are C-type. They are a mixture of C-, E-, M-, and P-types."[7]

Carbonaceous asteroids

"C-type asteroids are carbonaceous asteroids. They are the most common variety, forming around 75% of known asteroids,[8] and an even higher percentage in the outer part of the asteroid belt beyond 2.7 AU, which is dominated by this asteroid type. The proportion of C-types may actually be greater than this, because C-types are much darker than most other asteroid types except D-types and others common only at the extreme outer edge of the asteroid belt. ... Their spectra contain moderately strong ultraviolet absorption at wavelengths below about 0.4 μm to 0.5 μm, while at longer wavelengths they are largely featureless but slightly reddish. The so-called "water" absorption feature around 3 μm, which can be an indication of water content in minerals is also present."[9]

E asteroids

The "enstatite achondrite-like E-asteroids almost certainly derive from the melting and differentiation of highly reduced parent materials analogous to enstatite chondrites (e.g., Keil 1989)."[4]

F asteroids

"F-type asteroids have spectra generally similar to those of the B-type asteroids, but lack the "water" absorption feature around 3 μm indicative of hydrated minerals, and differ in the low wavelength part of the ultraviolet spectrum below 0.4 μm."[10]

G asteroids

"G-type asteroids are a relatively uncommon type of carbonaceous asteroid. The most notable asteroid in this class is 1 Ceres. ... Generally similar to the C-type objects, but containing a strong ultraviolet absorption feature below 0.5 μm."[11]

K asteroids

"Bell (1988) distinguished a new class (K-type) from previous members of the S-class and interpreted these objects as composed of material analogous to the undifferentiated CO3 ro CV3 carbonaceous chondrites."[4]

M asteroids

"Exposure of compositionally distinct internal layers from within parent planetesimals may be an important source of the diversity within the S-population and is presumably the source of the M- and A-type."[4]

R asteroids

"A-type asteroids are a relatively rare taxonomic class with no more than 17 known objects [1,2,3]. They were first identified as a separate group of R-type asteroids based on broadband spectrophotometry by [4], and were later classified based on ECAS data by Tholen (1984) [1]."[5]

Siliceous asteroids

"The presence of trapped solar gas in stony meteorites places their origin in the regoliths of asteroidal-type bodies. The most plausible sources are the C (carbonaceous) and S (siliceous) asteroids, in spite of the differences between the spectra of S asteroids and ordinary chondrites."[12]

"The S-asteroid class includes a number of distinct compositional subtypes [designated S(I)-S(VII)] which exhibit surface silicate assemblages ranging from pure olivine (dunites) through olivine-pyroxene mixtures to pure pyroxene or pyroxene-feldspar mixtures (basalts)."[4] These are shown in the graph on the right.

U asteroids

"The SU type represents an ambiguous classification with parameters of both the S- and the U-types but with the former more likely--Tholen 1984, 1989, Tholen and Barucci 1989."[4]

Earth crossers

EC denotes Earth-crossing.[3]

"50 % of the MB Mars-crossers [MCs] become ECs within 59.9 Myr and [this] contribution ... dominates the production of ECs".[3]

Apollo asteroids

|

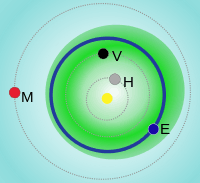

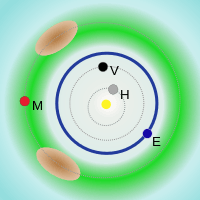

Mars (M) Venus (V) Mercury (H) |

Sun Apollo asteroids Earth (E) |

Note that sizes and distances of bodies and orbits are not to scale in the image on the right.

As of 2015, the Apollo asteroid group includes a total of 6,923 known objects of which 991 are numbered (JPL SBDB).

1999 JU3

"Asteroid 1999 JU3 is a so-called carbonaceous, or C-type, space rock — a different type of asteroid than the rocky (S-type) asteroid Itokawa visited by the first Hayabusa. Scientists suspect asteroid 1999 JU3 holds water and organic materials — some of the building blocks of the solar system."[13]

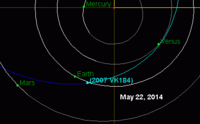

2007 VK184

"Recent observations have removed from NASA's asteroid impact hazard list the near-Earth object (NEO) known to pose the most significant risk of Earth impact over the next 100 years."[14]

"2007 VK184, an asteroid estimated to be roughly 130 meters in size, has been on NASA's Impact Risk Page maintained by the NEO Program Office at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) for several years, with an estimated 1-in-1800 chance of impacting Earth in June 2048. This predicted risk translates to a rating of 1 on the 10-point Torino Impact Hazard Scale. In recent months, 2007 VK184 has been the only known NEO with a non-zero Torino Scale rating."[14]

"2007 VK184 was discovered in November 2007 by the NASA-funded Catalina Sky Survey (CSS) at the University of Arizona and tracked by the CSS and other stations for two months before moving beyond view of ground based telescopes in January 2008."[14]

"But in the early morning hours of March 26 and 27, 2014, Dr. David Tholen of the University of Hawaii sighted 2007 VK184 once again. Using the 3.6-meter-diameter Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope at the Mauna Kea Observatories in Hawaii, he was able to detect and track the asteroid. Because it had not been observed for almost six years, its predicted position was only approximate. Nonetheless, Dr. Tholen was able to find it within the predicted search region, which is called a "recovery." He measured the asteroid's position and movement relative to the background of stars, and forwarded his tracking data to the Minor Planet Center (MPC) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the central node for the global NEO observer community."[14]

"Although the asteroid will be closer to Earth and brighter in May, I made the recovery attempt in March because I didn't want the position uncertainty to grow so much that it would force a time-consuming search of much more of the sky. The trade-off was increased exposure time to detect such a faint, distant object. Greater atmospheric turbulence on March 26 blurred the images of the asteroid enough to make the detection questionable, but the March 27 images were much better and confirmed the recovery."[15]

"The "Sentry" asteroid monitoring system at JPL automatically retrieved the new observations of 2007 VK184 from the MPC database, updated the orbit for the object, and computed a new impact hazard assessment. This new work shows that 2007 VK184 will pass no closer than 1.9 million kilometers (1.2 million miles) from the Earth in June 2048, with no closer encounters predicted for the foreseeable future. The NEO Program Office removed 2007 VK184 from the Impact Risk Page about three hours after receiving Dr. Tholen's observations from the MPC."[14]

"While these new observations of 2007 VK184 were challenging for Dave Tholen to obtain, they were reported quickly, and the global, distributed NEO impact hazard monitoring system worked smoothly to provide the all-clear for this object."[14]

"JPL's Sentry is an automated monitoring system that continually scans the most current catalog of known asteroids and predicts potential hazards of impacts with Earth over the next 100 years. As additional observations become available, objects will be removed from Sentry's Impact Risk Page when sufficient data become available to eliminate any potential for impact in the projected future. According to the Torino Impact Hazard Scale, developed and used by NEO observers to assess potential impact risks, a rating of 1 indicates a predicted event that "merits careful monitoring," and a rating of zero indicates the predicted event has "no likely consequences.""[14]

"Objects typically appear on the Sentry Impact Risk Page because a limited number of available observations may indicate a potential hazard of impact with Earth but do not provide astronomers enough information to precisely define their orbital movements. Whenever a newly discovered NEO is posted on the Sentry Impact Risk Page, the most likely outcome is that the object will eventually be removed as new observations become available, the object's orbit is more precisely known, and its future motion is more tightly constrained. NASA's NEO Program Office at JPL, which operates Sentry, receives asteroid observations and orbit predictions daily from the MPC. Once an asteroid is classified as a near-Earth object, the Sentry system automatically calculates orbit updates for it as new data become available."[14]

"NASA's Near-Earth Object Observation (NEOO) Program, located in the Planetary Science Division of the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., is responsible for finding, tracking, and characterizing near-Earth objects (NEOs) - asteroids and comets whose orbits periodically bring them close to Earth. The NEOO Program sponsors internal NASA and external research projects. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, manages a NEO Program Office for the Headquarters' NEOO Program and conducts a number of NASA-sponsored NEO projects."[14]

"Asteroid 2007 VK184 is another case study on how our system works."[16]

"We find them, track them, learn as much as we can about those found to be of special interest - an impact hazard or a space mission destination - and we predict and monitor their movement in the inner solar system until we know they are of no more concern."[16]

Mars crossers

"50 % of the MB Mars-crossers [MCs] become ECs within 59.9 Myr".[3]

Amor asteroids

Note that sizes and distances of bodies and orbits are not to scale. Credit: AndrewBuck.

2012 LZ1

The image at right is of asteroid 2012 LZ1 using the Arecibo Planetary Radar.

"On Sunday, June 10, a potentially hazardous asteroid thought to have been 500 meters (0.31 miles) wide was discovered by Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales, Australia. Fortunately for us, asteroid 2012 LZ1 drifted safely by, coming within 14 lunar distances from Earth on Thursday, June 14."[17]

"Asteroid 2012 LZ1 is actually bigger than thought… in fact, it is quite a lot bigger. 2012 LZ1 is one kilometer wide (0.62 miles), double the initial estimate."[17]

Asteroid "2012 LZ1′s surface is really dark, reflecting only 2-4 percent of the light that hits it — this contributed to the underestimated initial optical observations. Looking for an asteroid the shade of charcoal isn’t easy."[17]

“This object turned out to be quite a bit bigger than we expected, which shows how important radar observations can be, because we’re still learning a lot about the population of asteroids”.[13]

“The sensitivity of our radar has permitted us to measure this asteroid’s properties and determine that it will not impact the Earth at least in the next 750 years”.[18]

Mars Trojans

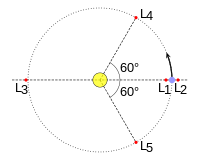

From the diagram in the section Amor asteroids, the Mars Trojans occupy comparable positions relative to Mars that the Trojan asteroids do to Jupiter.

Asteroid belts

Def. a "region of the orbital plane of the solar system located between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter which is occupied by numerous minor planets and the dwarf planet Ceres"[19] is called an asteroid belt.

"The MB group is the most numerous group of MCs. ... 50 % of the MB Mars-crossers [MCs] become ECs within 59.9 Myr and [this] contribution ... dominates the production of ECs"[3]. MB denotes the main belt of asteroids.[3]

"The interplanetary medium includes interplanetary dust, cosmic rays and hot plasma from the solar wind. The temperature of the interplanetary medium varies. For dust particles within the asteroid belt, typical temperatures range from 200 K (−73 °C) at 2.2 AU down to 165 K (−108 °C) at 3.2 AU[20] The density of the interplanetary medium is very low, about 5 particles per cubic centimeter in the vicinity of the Earth; it decreases with increasing distance from the sun, in inverse proportion to the square of the distance. It is variable, and may be affected by magnetic fields and events such as coronal mass ejections. It may rise to as high as 100 particles/cm³."[21]

"The hydromagnetic approach led to the discovery of two important observational regularities in the solar system: (1) the band structure [such as in the rings of Saturn and in the asteroid belt], and (2) the cosmogonic shadow effect (the two-thirds fall down effect)."[22]

"The majority of known asteroids orbit within the asteroid belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter ... This belt is now estimated to contain between 1.1 and 1.9 million asteroids larger than 1 km in diameter,[23] and millions of smaller ones.[24]"[25]

Nysian asteroids

The Nysian asteroids occur primarily between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter but some are between Earth and Mars.

446 Aeternitas

446 Aeternitas is an A asteroid.[4]

82 Alkmene

82 Alkmene is a siliceous asteroid type S(VI).[4]

113 Amalthea

113 Amalthea is a siliceous asteroid of subtype I [S(I)].[4]

29 Amphitrite

29 Amphitrite is a siliceous asteroid type S(V).[4]

99942 Apophis

There is some concern that the asteroid 99942 Apophis could impact Earth on April 13, 2036. It is about 210 - 330 meters in size. The probability of a collision is currently esitmated to be 1 in 45,000. These calculations are uncertain due to another close encounter in 2029 which will modify the orbit of the asteroid, making a collision either more or less likely. New measurements possible in 2011-2013 will likely confirm that the asteroid will miss the Earth.

197 Arete

"More than 150 years after the discovery of 4 Vesta in 1807, Hertz (1966) made the first asteroid mass determination by analyzing its perturbation on 197 Arete."[26]

43 Ariadne

43 Ariadne is a siliceous asteroid of subtype III [S(III)].[4]

67 Asia

67 Asia is a siliceous asteroid type S(IV).[4]

246 Asporina

246 Asporina is an A-type asteroid.[5]

63 Ausonia

63 Ausonia is a siliceous asteroid of subtype III [S(III)].[4]

"Ausonia is classed ambiguously as type S(II-III)."[4]

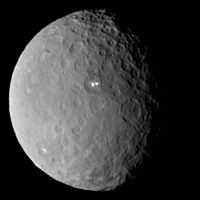

1 Ceres

"High-resolution ultraviolet Hubble Space Telescope images taken in 1995 showed a dark spot on its surface which was nicknamed "Piazzi" in honour of the discoverer of Ceres.[27] This was thought to be a crater. Later near-infrared images with a higher resolution taken over a whole rotation with the Keck telescope using adaptive optics showed several bright and dark features moving with the dwarf planet's rotation.[28][29]"[30]

354 Eleonora

354 Eleonora is a siliceous asteroid of subtype I [S(I)].[4]

433 Eros

"In 2000, 433 Eros became the first asteroid to be orbited by a spacecraft, NEAR Shoemaker (Yeomans et al., 2000)."[26]

15 Eunomia

15 Eunomia is a siliceous asteroid of subtype III [S(III)].[4]

27 Euterpe

27 Euterpe is a siliceous asteroid type S(IV).[4]

37 Fides

37 Fides is a siliceous asteroid type S(V).[4]

8 Flora

8 Flora may be ambiguously a type S(II-III) siliceous asteroid.[4]

1036 Ganymed

1036 Ganymed is a siliceous asteroid type S(VI-VII).[4]

951 Gaspra

The "Galileo flyby images of 951 Gaspra suggest the presence of some regolith on that 16- by 12-km object (e.g., Belton et al. 1992)."[4]

40 Harmonia

40 Harmonia is a siliceous asteroid type S(VII).[4]

6 Hebe

6 Hebe is a siliceous asteroid of subtype IV [S(IV)].[4]

The image on the right is a photograph of 6 Hebe (the brightest spot) in 2004.

"Compositional analysis of 2007 LE reveal Fs17 and Fa19 values, which are consistent with the Fa and Fs values for the H-type ordinary chondrites (Fs14.5–18 and Fa16–20) and of Asteroid (6) Hebe (Fs17 and Fa15)."[31]

"It is probable that the H-chondrites and IIE irons came from (6) Hebe (Gaffey and Gilbert, 1998), though caveats exist (e.g., Rubin and Bottke, 2009)."[31]

101 Helena

101 Helena is a siliceous asteroid type S(V).[4]

532 Herculina

532 Herculina is a siliceous asteroid of subtype III [S(III)].[4]

243 Ida

"This is the first full picture [on the right] showing both asteroid 243 Ida and its newly discovered moon to be transmitted to Earth from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA's) Galileo spacecraft--the first conclusive evidence that natural satellites of asteroids exist. Ida, the large object, is about 56 kilometers (35 miles) long. Ida's natural satellite is the small object to the right. This portrait was taken by Galileo's charge-coupled device (CCD) camera on August 28, 1993, about 14 minutes before the Jupiter-bound spacecraft's closest approach to the asteroid, from a range of 10,870 kilometers (6,755 miles). Ida is a heavily cratered, irregularly shaped asteroid in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter--the 243rd asteroid to be discovered since the first was found at the beginning of the 19th century. Ida is a member of a group of asteroids called the Koronis family. The small satellite, which is about 1.5 kilometers (1 mile) across in this view, has yet to be given a name by astronomers. It has been provisionally designated '1993 (243) 1' by the International Astronomical Union. ('1993' denotes the year the picture was taken, '243' the asteroid number and '1' the fact that it is the first moon of Ida to be found.) Although appearing to be 'next' to Ida, the satellite is actually in the foreground, slightly closer to the spacecraft than Ida is. Combining this image with data from Galileo's near-infrared mapping spectrometer, the science team estimates that the satellite is about 100 kilometers (60 miles) away from the center of Ida. This image, which was taken through a green filter, is one of a six-frame series using different color filters. The spatial resolution in this image is about 100 meters (330 feet) per pixel."[32]

On the second lower right is an approximately natural color image of the asteroid 243 Ida. "There are brighter areas, appearing bluish in the picture, around craters on the upper left end of Ida, around the small bright crater near the center of the asteroid, and near the upper right-hand edge (the limb). This is a combination of more reflected blue light and greater absorption of near infrared light, suggesting a difference in the abundance or composition of iron-bearing minerals in these areas."[33]

389 Industria

389 Industria is a siliceous asteroid type S(V).[4]

364 Isara

364 Isara is a siliceous asteroid of subtype II [S(II)].[4]

42 Isis

42 Isis is a siliceous asteroid of subtype I [S(I)].[4]

89 Julia

89 Julia is a siliceous asteroid.[4]

3 Juno

3 Juno is a siliceous asteroid type S(IV).[4]

39 Laetitia

39 Laetitia is a siliceous asteroid of subtype II [S(II)].[4]

68 Leto

68 Leto is a siliceous asteroid of subtype II [S(II)].[4]

264 Libussa

264 Libussa is a siliceous asteroid type S(V).[4]

20 Massalia

20 Massalia is a siliceous asteroid type S(VI).[4]

253 Mathilde

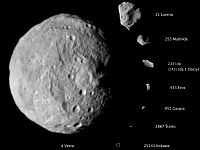

_mathilde.jpg)

Mathide is a carbonaceous (C) asteroid.

"The masses of 253 Mathide (Yeomans et al., 1998) and Eros (Yeomans et al., 2000) are the first two asteroid masses determined by observing the perturbation of a spacecraft in the vicinity of the asteroid."[26]

18 Melpomene

18 Melpomene is a siliceous asteroid type S(V).[4]

9 Metis

9 Metis is a siliceous asteroid.[4]

57 Mnemosyne

57 Mnemosyne is a siliceous asteroid type S(VII).[4]

289 Nenetta

289 Nenetta is an A asteroid.[4]

2 Pallas

"Pallas, minor-planet designation 2 Pallas, is the second asteroid to have been discovered (after Ceres), and one of the largest in the Solar System. It is estimated to comprise 7% of the mass of the asteroid belt,[34] and its diameter of 544 kilometres (338 mi) is slightly larger than that of 4 Vesta. It is however 10–30% less massive than Vesta,[35] placing it third among the asteroids."[36]

11 Parthenope

11 Parthenope is a siliceous asteroid type S(IV).[4]

25 Phocaea

25 Phocaea is a siliceous asteroid type S(IV).[4]

33 Polyhymnia

33 Polyhymnia is a siliceous asteroid type S(IV).[4]

26 Proserpina

26 Proserpina is a siliceous asteroid of subtype II [S(II)].[4]

674 Rachele

674 Rachele is a siliceous asteroid of subtype VII [S(VII)].[4]

335 Roberta

335 Roberta is a blue asteroid.[6]

80 Sappho

80 Sappho is a siliceous asteroid type S(IV).[4]

584 Semiramis

584 Semiramis is a siliceous asteroid type S(IV).[4]

115 Thyra

115 Thyra is a siliceous asteroid of subtype III [S(III)].[4]

4179 Toutatis

At right is a Goldstone radar image of the asteroid 4179 Toutatis on November 26, 1996.

The "images were recorded at NASA's Deep Space Network 70-meter and 34-meter radio/radar antennas in Goldstone, CA, and the 305-meter Arecibo Radio Telescope in Puerto Rico."[37]

"It's amazing that the shape of Toutatis can be determined so accurately from ground-based observations".[38]

"This technology will provide us with startling, close-up views of thousands of asteroids that orbit near the Earth."[38]

"We used the computer to mathematically create a three- dimensional model of the surface and rotation of Toutatis".[39]

"It's as though we put a clay model in space and molded it until it matched the appearance of the actual asteroid."[39]

"The video is of particular interest as Toutatis nears Earth and makes its closest approach on Friday, Nov. 29, when it will pass by at a distance of 3.3 million miles (5.3 million kilometers), or about 14 times the distance from the Earth to the Moon. In 2004, Toutatis will pass only four lunar distances from Earth, closer than any known Earth- approaching object expected to pass by in the next 60 years."[37]

"Toutatis poses no significant threat to Earth, at least for a few hundred years".[40]

"The discovery that we live in an asteroid swarm is important for the future of humanity".[40]

"These leftover debris from planetary formation can teach us a good deal about the formation of our Solar System. Asteroids also contain valuable minerals and many are the cheapest possible destinations for space missions."[40]

On September 29, 2004 the asteroid 4179 Toutatis made a particularly close approach (within 4 LD, or lunar distances) from Earth. The next close approach is November 9, 2008, but it will be five times more distant. It is about 4.6 km by 2.4 km in size.

258 Tyche

258 Tyche is a siliceous asteroid type S(V).[4]

4 Vesta

"The [NASA's Dawn spacecraft] Framing Camera (FC) discovered enigmatic orange material on Vesta. FC images revealed diffuse orange ejecta around two impact craters, 34-km diameter Oppis, and 30-km diameter Octavia, as well as numerous sharp-edge orange units in the equatorial region."[41] The spacecraft "entered orbit around asteroid (4) Vesta in July 2011 for a year-long mapping orbit."[41]

"Using Dawn’s Gamma Ray and Neutron Detector, ... Global Fe/O and Fe/Si ratios are consistent with [howardite, eucrite, and diogenite] HED [meteorite] compositions."[42]

"To prepare for the Dawn spacecraft's visit to Vesta, astronomers used Hubble's Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 to snap new images of the asteroid. The image at right was taken on May 14 and 16, 2007. Using Hubble, astronomers mapped Vesta's southern hemisphere, a region dominated by a giant impact crater formed by a collision billions of years ago. The crater is 285 miles (456 kilometers) across, which is nearly equal to Vesta's 330-mile (530-kilometer) diameter. If Earth had a crater of proportional size, it would fill the Pacific Ocean basin. The impact broke off chunks of rock, producing more than 50 smaller asteroids that astronomers have nicknamed "vestoids." The collision also may have blasted through Vesta's crust. Vesta is about the size of Arizona."[43]

"Previous Hubble images of Vesta's southern hemisphere were taken in 1994 and 1996 with the wide-field camera. In this new set of images, Hubble's sharp "eye" can see features as small as about 37 miles (60 kilometers) across. The image shows the difference in brightness and color on the asteroid's surface. These characteristics hint at the large-scale features that the Dawn spacecraft [sees] when it arrives at Vesta."[43]

"Hubble's view reveals extensive global features stretching longitudinally from the northern hemisphere to the southern hemisphere. The image also shows widespread differences in brightness in the east and west, which probably reflects compositional changes. Both of these characteristics could reveal volcanic activity throughout Vesta. The size of these different regions varies. Some are hundreds of miles across."[43]

"The brightness differences could be similar to the effect seen on the Moon, where smooth, dark regions are more iron-rich than the brighter highlands that contain minerals richer in calcium and aluminum. When Vesta was forming 4.5 billion years ago, it was heated to the melting temperatures of rock. This heating allowed heavier material to sink to Vesta's center and lighter minerals to rise to the surface."[43]

"Astronomers combined images of Vesta in two colors to study the variations in iron-bearing minerals. From these minerals, they hope to learn more about Vesta's surface structure and composition."[43]

"The simplest model for the genesis of the HED meteorites involves a series of partial melting and crystallization events [1] of a small parent body whose bulk composition is more or less consistent with cosmic abundances but is depleted in the moderately volatile elements Na and K [2]."[44]

"Why should both Vesta and the Moon be rich in oxidized Fe but depleted in Na and K?"[44]

"How did the HEDs get here from Vesta? The discovery of a string of Vesta-like asteroids in orbits linking Vesta to nearby orbital resonances [5] has shown that [...] arguments [...] for material originating at Vesta to reach Earth-crossing orbits are [...] valid."[44]

"An alternative theory is based on electromagnetic heating during an episode of strong solar wind from the early proto-Sun when our star experienced a T Tauri phase, as predicted by modern stellar astrophysics."[45]

12 Victoria

12 Victoria is a siliceous asteroid of subtype II [S(II)].[4]

Trojan asteroids

Def. "the L4 and L5 Lagrange points of the Sun-Jupiter orbital configuration"[46] are called the Trojan points.

Def. "an asteroid occupying the Trojan points of the Sun-Jupiter system"[47] is called a Trojan asteroid.

Centaurs

Def. an "icy planetoid that orbits the Sun between Jupiter and Neptune"[48] is called a Centaur.

"The recent investigation of the orbital distribution of Centaurs (Emel’yanenko et al., 2005) showed that there are two dynamically distinct classes of Centaurs, a dominant group with semimajor axes a > 60 AU and a minority group with a < 60 AU."[49] "[T]he intrinsic number of such objects is roughly an order of magnitude greater than that for a<60 AU".[49]

Explorers

"The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency's (JAXA) Hayabusa2 asteroid mission blasted off Tuesday (Dec. 2) at 11:22 p.m. EST (0422 GMT Dec. 3) from the country's Tanegashima Space Center, where the local time at liftoff was 1:22 p.m. on Wednesday, Dec. 3. If all goes well, the spacecraft should return samples of the asteroid 1999 JU3 to Earth in late 2020, JAXA officials said."[13]

"Hayabusa2 is JAXA's bigger, bolder follow-up to its historic Hayabusa mission, which brought the first pristine samples of an asteroid to Earth in 2010 after its own seven-year mission."[13]

"Minerals and seawater which form the Earth as well as materials for life are believed to be strongly connected in the primitive solar nebula in the early solar system. Thus we expect to clarify the origin of life by analyzing samples acquired from a primordial celestial body such as [this] asteroid to study organic matter and water in the solar system, and how they coexist while affecting each other."[50]

"While Hayabusa2 studies asteroid 1999 JU3 from orbit, it will deploy three rovers and a German/European lander called MASCOT, all of which will work independently on the surface to gather information on the asteroid's composition and history."[13]

"The spacecraft will make three landings by itself, each time putting the material collected in a separate chamber for return to Earth. Meanwhile, three rovers (collectively called Minerva II) and the small MASCOT lander will transmit information from the surface to Hayabusa2."[13]

"After completing operations at 1999 JU3, Hayabusa2 will then make the one-year journey back to Earth for an expected landing in the Australian outback late in 2020."[13]

Research

Hypothesis:

- Asteroids are any-size rocky astronomical objects.

Control groups

The findings demonstrate a statistically systematic change from the status quo or the control group.

“In the design of experiments, treatments [or special properties or characteristics] are applied to [or observed in] experimental units in the treatment group(s).[51] In comparative experiments, members of the complementary group, the control group, receive either no treatment or a standard treatment.[52]"[53]

Proof of concept

Def. a “short and/or incomplete realization of a certain method or idea to demonstrate its feasibility"[54] is called a proof of concept.

Def. evidence that demonstrates that a concept is possible is called proof of concept.

The proof-of-concept structure consists of

- background,

- procedures,

- findings, and

- interpretation.[55]

See also

References

- 1 2 "asteroid, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 13 August 2015. Retrieved 2015-08-31.

- ↑ Paul Robert Weissman, Torrence V. Johnson (2007). Lucy-Ann Adams McFadden, Paul Robert Weissman, Torrence V. Johnson. ed. Encyclopedia of the Solar System, Second Edition. San Diego, California, USA: Academic Press. pp. 966. ISBN 0120885891. http://books.google.com/books?id=G7UtYkLQoYoC&lr=&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Patrick Michel, Fabbio Migliorini, Alessandro Morbidelli, Vincenzo Zappalà (June 2000). "The Population of Mars-Crossers: Classification and Dynamical Evolution". Icarus 145 (2): 332-47. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6358. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0019103500963589. Retrieved 2011-10-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 Michael J. Gaffey, Jeffrey F. Bell, R. Hamilton Brown, Thomas H. Burbine, Jennifer L. Piatek, Kevin L. Reed, and Damon A. Chaky (December 1993). "Mineralogical variations within the S-type asteroid class". Icarus 106 (2): 573-602. http://www.mtholyoke.edu/~tburbine/gaffey.icarus.1993.pdf. Retrieved 2015-09-03.

- 1 2 3 4 V. Reddy, P. S. Hardersen, M. J. Gaffey, and P. A. Abell (2005). Mineralogic and Temperature-Induced Spectral Investigations of A-type Asteroids 246 Asporina and 446 Aeternitas, In: Lunar and Planetary Science. XXXVI. USRA. pp. 2. http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2005/pdf/1375.pdf. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- 1 2 3 Bin Yang and David Jewitt (September 2010). "Identification of Magnetite in B-type Asteroids". The Astronomical Journal 140 (3): 692. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/140/3/692. http://iopscience.iop.org/1538-3881/140/3/692. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- ↑ F Yoshida, T Nakamura (June 2007). "Subaru main belt asteroid survey (SMBAS)—size and color distributions of small main-belt asteroids". Planetary and Space Science 55 (9): 1113-25. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2006.11.016. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0032063306003357. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- ↑ Gradie et al. pp. 316-335 in Asteroids II. edited by Richard P. Binzel, Tom Gehrels, and Mildred Shapley Matthews, Eds. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, 1989, ISBN 0-8165-1123-3

- ↑ "C-type asteroid, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. June 21, 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-30.

- ↑ "F-type asteroid, in: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. February 26, 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-30.

- ↑ "G-type asteroid, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. June 21, 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-30.

- ↑ E. Anders (1978). Most stony meteorites come from the asteroid belt, In: NASA, Washington Asteroids. N78-29007. Washington, DC USA: NASA. pp. 57-75. Bibcode: 1978astd.nasa...57A. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1978astd.nasa...57A. Retrieved 2015-09-03.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ellen Howell (June 22, 2012). "Asteroid 2012 LZ1 Just Got Supersized". Discovery Communications, LLC. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Steven Chesley (2 April 2014). "Asteroid 2007 VK184 Eliminated as Impact Risk to Earth". Pasadena, California USA: NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2015-09-02.

- ↑ David Tholen (2 April 2014). "Asteroid 2007 VK184 Eliminated as Impact Risk to Earth". Pasadena, California USA: NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2015-09-02.

- 1 2 Lindley Johnson (2 April 2014). "Asteroid 2007 VK184 Eliminated as Impact Risk to Earth". Pasadena, California USA: NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2015-09-02.

- 1 2 3 Ian O'Neill (June 22, 2012). "Asteroid 2012 LZ1 Just Got Supersized". Discovery Communications, LLC. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

- ↑ Mike Nolan (June 22, 2012). "Asteroid 2012 LZ1 Just Got Supersized". Discovery Communications, LLC. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

- ↑ WikiPedant (10 December 2007). "asteroid belt, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-08-31.

- ↑ Low, F. J.; et al. (1984). "Infrared cirrus – New components of the extended infrared emission". Astrophysical Journal, Part 2 – Letters to the Editor 278: L19–L22. doi:10.1086/184213. http://adsabs.harvard.edu//abs/1984ApJ...278L..19L.

- ↑ "Interplanetary medium, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. March 14, 2013. Retrieved 2013-05-13.

- ↑ Hannes Alfvén (October 1981). "The Voyager 1/Saturn Encounter and the Cosmogonic Shadow Effect". Astrophysics and Space Science 79 (2): 491-505. doi:10.1007/BF00649444. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1981Ap&SS..79..491A. Retrieved 2013-12-19.

- ↑ Edward Tedesco, Leo Metcalfe (April 4, 2002). "New study reveals twice as many asteroids as previously believed". European Space Agency. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ↑ World Book at NASA

- ↑ "Asteroid, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. June 29, 2012. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- 1 2 3 James L. Hilton (January 1, 2002). William Frederick Bottke. ed. Asteroid Masses and Densities, In: Asteroids III. Tucson, Arizona USA: University of Arizona Press. pp. 103-20. ISBN 0816522812. http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=JwHTyO6IHh8C&oi=fnd&pg=PA235&ots=AI9aRiuWcM&sig=2dO3vVO2i-v_oO0zGwe_zzg_p0M. Retrieved 2014-01-10.

- ↑ Parker, J. W.; Stern, Alan S.; Thomas Peter C.; et al. (2002). "Analysis of the first disk-resolved images of Ceres from ultraviolet observations with the Hubble Space Telescope". The Astrophysical Journal 123 (1): 549–557. doi:10.1086/338093.

- ↑ Carry, Benoit; et al. (November 2007). "Near-Infrared Mapping and Physical Properties of the Dwarf-Planet Ceres" (PDF). Astronomy & Astrophysics 478 (1): 235–244. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078166. Archived from the original on 2008-05-30. http://web.archive.org/20080530130946/www2.keck.hawaii.edu/inst/people/conrad/nsfGrantRef/2007-arXiv-Benoit.Carry.pdf.

- ↑ Staff (2006-10-11). "Keck Adaptive Optics Images the Dwarf Planet Ceres". Adaptive Optics. Archived from the original on 2010-01-18. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ↑ "Ceres (dwarf planet), In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. June 29, 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-30.

- 1 2 Sherry K. Fieber-Beyer, Michael J. Gaffey, William F. Bottke, Paul S. Hardersen (2015). "Potentially hazardous Asteroid 2007 LE: Compositional link to the black chondrite Rose City and Asteroid (6) Hebe". Icarus 250: 430-7. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2014.12.021. http://www.boulder.swri.edu/~bottke/Reprints/Fieber_Beyer_2015_Icarus_250_430_Link_2007LE_Black_Chondrite.pdf. Retrieved 2015-09-24.

- ↑ Sue Lavoie (February 1, 1996). "PIA00136: Asteroid Ida and Its Moon". Pasadena, California USA: NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- ↑ Sue Lavoie (January 29, 1996). "PIA00069: Ida and Dactyl in Enhanced Color". Pasadena, California USA: NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- ↑ Elena V. Pitjeva (2005). "High-Precision Ephemerides of Planets—EPM and Determination of Some Astronomical Constants". Solar System Research 39 (3): 176. doi:10.1007/s11208-005-0033-2. http://iau-comm4.jpl.nasa.gov/EPM2004.pdf.

- ↑ James Baer and Steven R. Chesley (2008). "Astrometric masses of 21 asteroids, and an integrated asteroid ephemeris". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy 100 (2008): 27–42. doi:10.1007/s10569-007-9103-8. http://www.springerlink.com/content/h747307j43863228/fulltext.pdf. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- ↑ "2 Pallas, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. February 28, 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- 1 2 Don Savage and Jane Platt (November 27, 1996). "Images of Asteroid 4179 Toutatis". Washington, DC USA: NASA. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

- 1 2 Eric De Jong (November 27, 1996). "Images of Asteroid 4179 Toutatis". Washington, DC USA: NASA. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

- 1 2 Scott Hudson (November 27, 1996). "Images of Asteroid 4179 Toutatis". Washington, DC USA: NASA. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

- 1 2 3 Steven Ostro (November 27, 1996). "Images of Asteroid 4179 Toutatis". Washington, DC USA: NASA. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

- 1 2 L Le Corre, V Reddy, KJ Becker (October 2012). "Nature of Orange Ejecta Around Oppia and Octavia Craters on Vesta from Dawn Framing Camera". American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting (44).

- ↑ Thomas H. Prettyman, David W. Mittlefehidt, Naoyuki Yamashita, David J. Lawrence, Andrew W. Beck, William C. Feldman, Timothy J. McCoy, Harry Y. McSween, Michael J. Toplis, Timothy N. Titus, Pasquale Tricarico, Robert C. Reedy, John S. Hendricks, Olivier Forni, Lucille Le Corre, Jian-Yang Li, Hugau Mizzon, Vishnu Reddy, Carol A. Raymond, Christopher T. Russell (October 2012). "Elemental Mapping by Dawn Reveals Exogenic H in Vesta's Regolith". Science 338 (6104): 242-6. doi:10.1126/science.1225354.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ray Villard and Lucy McFadden (June 20, 2007). "Hubble Images of Asteroids Help Astronomers Prepare for Spacecraft Visit". Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, Md USA: HubbleSite. Retrieved 2013-12-22.

- 1 2 3 G. J. Consolmagno (January 1996). "Cosmogonic Implications of the HED-Vesta Connection". Workshop on Evolution of Igneous Asteroids: Focus on Vesta and the HED Meteorites: 6. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1996eiaf.conf....6C. Retrieved 2013-12-22.

- ↑ L. Bussolino, R. Sommat, C. Casaccit, V. Zappala, A. Cellino, and M. Di Martino (January 1996). "A Space Mission to Vesta: General Considerations". Workshop on Evolution of Igneous Asteroids: Focus on Vesta and the HED Meterorites (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1996eiaf.conf....5B): 5.

- ↑ 65.94.44.124 (11 December 2010). "Trojan point, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-08-31.

- ↑ 65.94.44.124 (11 December 2010). "Trojan asteroid, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-08-31.

- ↑ SnoopY (21 December 2005). "Centaur, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-08-31.

- 1 2 V. V. Emel’yanenko (December 2005). "Structure and dynamics of the Centaur population: constraints on the origin of short-period comets". Earth, Moon, and Planets 97 (3-4): 341-51. doi:10.1007/s11038-006-9095-5. http://www.springerlink.com/content/k6n4251846112n17/. Retrieved 2011-10-06.

- ↑ JAXA (02 December 2014). "Japan Launches Asteroid-chasing Probe to Bring Space Rock Samples to Earth". SPACE.com. Retrieved 2014-12-08.

- ↑ Klaus Hinkelmann, Oscar Kempthorne (2008). Design and Analysis of Experiments, Volume I: Introduction to Experimental Design (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-72756-9. http://books.google.com/?id=T3wWj2kVYZgC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ R. A. Bailey (2008). Design of comparative experiments. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68357-9. http://www.cambridge.org/uk/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521683579.

- ↑ "Treatment and control groups, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. May 18, 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-31.

- ↑ "proof of concept, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. November 10, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ↑ Ginger Lehrman and Ian B Hogue, Sarah Palmer, Cheryl Jennings, Celsa A Spina, Ann Wiegand, Alan L Landay, Robert W Coombs, Douglas D Richman, John W Mellors, John M Coffin, Ronald J Bosch, David M Margolis (August 13, 2005). "Depletion of latent HIV-1 infection in vivo: a proof-of-concept study". Lancet 366 (9485): 549-55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67098-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1894952/. Retrieved 2012-05-09.

External links

![]() This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

| |

Educational level: this is a research resource. |

| |

Resource type: this resource is an article. |

| |

Resource type: this resource contains a lecture or lecture notes. |

| |

Subject classification: this is an astronomy resource. |