Pluto

Pluto is the second largest dwarf planet known (after Eris).

Astronomy

_without_labels.jpg)

In the image on the right are shown from left to right: Pluto, Charon, Nix and Hydra.

Planetary science

"Over the weekend, scientists discovered that it is a bit bigger than they expected. Previous estimates had put it somewhere between 715 and 746 miles, but new information suggests Pluto's radius is about 736 miles across, putting it solidly at the upper end of the estimate."[1]

Opticals

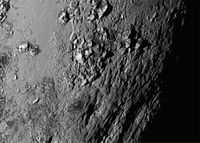

"At heights of about 11,000 feet, the Norgay Montes [on the right] most closely approximates the height of the Rockies."[2]

"NASA scientists identified this newfound range of water-ice mountains [on the left] based on high-res images obtained by the New Horizons spacecraft."[3]

"The mountain range is located in the dwarf planet's heart-shaped feature, called Tombaugh Regio after Pluto's discoverer, Clyde Tombaugh. The mountains rise to about the height of the Appalachian Mountains on Earth, which reach a maximum height of about 6,000 feet."[3]

Recent history

The recent history period dates from around 1,000 b2k to present.

Pluto was discovered on February 18, 1930, by Clyde Tombaugh.

Research

Hypothesis:

- Pluto and its satellites may have been in orbit around Jupiter.

Control groups

The findings demonstrate a statistically systematic change from the status quo or the control group.

“In the design of experiments, treatments [or special properties or characteristics] are applied to [or observed in] experimental units in the treatment group(s).[4] In comparative experiments, members of the complementary group, the control group, receive either no treatment or a standard treatment.[5]"[6]

Proof of concept

Def. a “short and/or incomplete realization of a certain method or idea to demonstrate its feasibility"[7] is called a proof of concept.

Def. evidence that demonstrates that a concept is possible is called proof of concept.

The proof-of-concept structure consists of

- background,

- procedures,

- findings, and

- interpretation.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ Deborah Netburn (14 July 2015). "Pluto is now the most distant object ever visited by humanity". Los Angeles, California USA: Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2015-07-14.

- ↑ Jeff Moore (21 July 2015). "High resolution photo shows another set of ice mountains on Pluto". Mashable.com. Retrieved 2015-07-23.

- 1 2 Miriam Kramer (21 July 2015). "High resolution photo shows another set of ice mountains on Pluto". Mashable.com. Retrieved 2015-07-23.

- ↑ Klaus Hinkelmann, Oscar Kempthorne (2008). Design and Analysis of Experiments, Volume I: Introduction to Experimental Design (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-72756-9. http://books.google.com/?id=T3wWj2kVYZgC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ R. A. Bailey (2008). Design of comparative experiments. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68357-9. http://www.cambridge.org/uk/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521683579.

- ↑ "Treatment and control groups, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. May 18, 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-31.

- ↑ "proof of concept, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. November 10, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ↑ Ginger Lehrman and Ian B Hogue, Sarah Palmer, Cheryl Jennings, Celsa A Spina, Ann Wiegand, Alan L Landay, Robert W Coombs, Douglas D Richman, John W Mellors, John M Coffin, Ronald J Bosch, David M Margolis (August 13, 2005). "Depletion of latent HIV-1 infection in vivo: a proof-of-concept study". Lancet 366 (9485): 549-55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67098-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1894952/. Retrieved 2012-05-09.

External links

| |

Development status: this resource is experimental in nature. |

| |

Subject classification: this is an astronomy resource. |

| |

Educational level: this is a research resource. |

| |

Resource type: this resource is an article. |