Parseval's theorem

In mathematics, Parseval's theorem usually refers to the result that the Fourier transform is unitary; loosely, that the sum (or integral) of the square of a function is equal to the sum (or integral) of the square of its transform. It originates from a 1799 theorem about series by Marc-Antoine Parseval, which was later applied to the Fourier series.

Although the term "Parseval's theorem" is often used to describe the unitarity of any Fourier transform, especially in physics and engineering, the most general form of this property is more properly called the Plancherel theorem.

Statement of Parseval's theorem

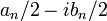

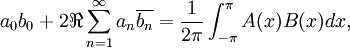

Suppose that A(x) and B(x) are two Riemann integrable, complex-valued functions on R of period 2π with (formal) Fourier series

and

and

respectively. Then

where i is the imaginary unit and horizontal bars indicate complex conjugation.

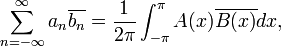

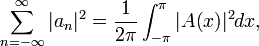

Parseval, who apparently had confined himself to real-valued functions, actually presented the theorem without proof, considering it to be self-evident. There are various important special cases of the theorem. First, if A = B one immediately obtains:

from which the unitarity of the Fourier series follows.

Second, one often considers only the Fourier series for real-valued functions A and B, which corresponds to the special case:  real,

real,  ,

,  real, and

real, and  . In this case:

. In this case:

where  denotes the real part. (In the notation of the Fourier series article, replace

denotes the real part. (In the notation of the Fourier series article, replace  and

and  by

by  .)

.)

Applications

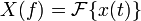

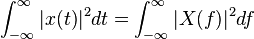

In physics and engineering, Parseval's theorem is often written as:

- where

represents the continuous Fourier transform (in normalized, unitary form) of x(t) and f represents the frequency component (not angular frequency) of x.

represents the continuous Fourier transform (in normalized, unitary form) of x(t) and f represents the frequency component (not angular frequency) of x.

The interpretation of this form of the theorem is that the total energy contained in a waveform x(t) summed across all of time t is equal to the total energy of the waveform's Fourier Transform X(f) summed across all of its frequency components f.

For discrete time signals, the theorem becomes:

- where X is the discrete-time Fourier transform (DTFT) of x and φ represents the angular frequency (in radians per sample) of x.

Alternatively, for the discrete Fourier transform (DFT), the relation becomes:

- where X[k] is the DFT of x[n], both of length N.

See also

- Bessel's inequality

- Parseval's identity

- School:Mathematics

References

- Parseval, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- George B. Arfken and Hans J. Weber, Mathematical Methods for Physicists (Harcourt: San Diego, 2001).

- Hubert Kennedy, Eight Mathematical Biographies (Peremptory Publications: San Francisco, 2002).

- Alan V. Oppenheim and Ronald W. Schafer, Discrete-Time Signal Processing 2nd Edition (Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 1999) p 60.

- William McC. Siebert, Circuits, Signals, and Systems (MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 1986), pp. 410-411.

External links

- Parseval's Theorem on Mathworld

- In the movie Good Will Hunting, the theorem that Professor Lambeau finishes writing on the classroom chalkboard just after we first see him is Parseval's theorem.

![\sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} | x[n] |^2 = \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\pi}^{\pi} | X(e^{j\phi}) |^2 d\phi](../I/m/703bb1e521501f32c1b0d68c081d6ef2.png)

![\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} | x[n] |^2 = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{k=0}^{N-1} | X[k] |^2](../I/m/dd3e997e03ee61f3c43c2e96731deb83.png)