Nonlinear finite elements/Weak form of heat equation

< Nonlinear finite elementsWeak Form of the Heat Equation

Let us now derive the weak form of the model of heat conduction in equations (16). It is more convenient to use the form of the governing equation given in equation (10). The equation is

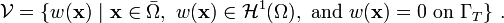

Let  be the space of weighting functions (or test functions). Then

any

be the space of weighting functions (or test functions). Then

any  (

( ) is continuously

differentiable. The weighting functions also satisfy

) is continuously

differentiable. The weighting functions also satisfy  on

on

. Recall that we called a similar set of functions

. Recall that we called a similar set of functions  in

our discussion of the Poisson problem. We can write

in

our discussion of the Poisson problem. We can write

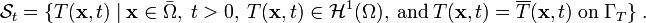

Let  be the set of trial solutions. Then any trial function

be the set of trial solutions. Then any trial function

has to satisfy the essential boundary conditions

on

has to satisfy the essential boundary conditions

on  . This is written as

. This is written as

To get the weak form, we multiply the governing equation by the weighting function and integrate over the volume to get

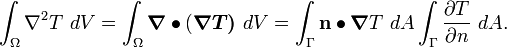

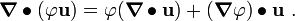

The second term in the equation has second-order derivatives. We will convert these into first order derivatives using the divergence theorem and the identity

From the identity we get

Substitute (29) into the second term in (28) to get

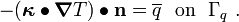

Apply the divergence theorem to the first term on the right hand side of (30). You will get

where  is the unit outward normal to the boundary

is the unit outward normal to the boundary  .

.

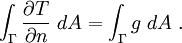

Since  on

on  , equation (31) becomes

, equation (31) becomes

Substitute (31) into (30) and (30) back into (28). You will get

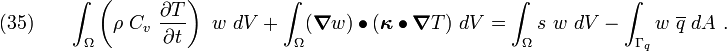

After rearrangement, we get the exact weak form of the heat equation

Recall that equation (15) gives us

Therefore equation (34) can be written as

In more compact notation

Following the same process for the initial condition, we get

In compact notation,

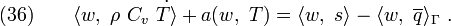

The variation initial boundary value problem for heat conduction can then be stated as follows.

Well-Posedness of the Boundary Value Problem

Unless  has a simple geometry - square, spherical or cylindrical,

it is very difficult to solve the BVP in closed form (using separation

of variables, for instance). For some BVPs, it may not be possible

at all to get a closed form solution. In fact, it may not even be

obvious that a solution exists or is unique or that the solution depends

continuously on the data.

has a simple geometry - square, spherical or cylindrical,

it is very difficult to solve the BVP in closed form (using separation

of variables, for instance). For some BVPs, it may not be possible

at all to get a closed form solution. In fact, it may not even be

obvious that a solution exists or is unique or that the solution depends

continuously on the data.

A well-posed problem is one that satisfied the three conditions:

- a solution exists.

- the solution is unique.

- the solution depends continuously on the data (that is, smallchanges in the data do not cause wild fluctuations in the solution).

BVPs can be used to get reliable results only when they are well-posed.

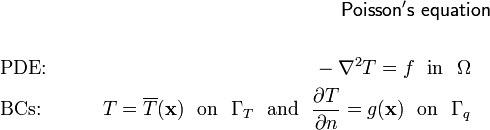

Let us look at an example. Recall the BVP for the Poisson equation.

Assume that  . That means that the heat flux is given on

the entire boundary.

. That means that the heat flux is given on

the entire boundary.

Suppose  is a solution. Then

is a solution. Then  is also a solution, where

is also a solution, where  is a constant. To see why, compute the Laplacian of

is a constant. To see why, compute the Laplacian of  .

.

So the solution  satisfies the PDE.

satisfies the PDE.

How about the boundary conditions?Plug in  into the boundary

condition to get

into the boundary

condition to get

So the boundary conditions are also satisfied. That means that if

, then the solution is not unique. We can

add any constant temperature to the body and the solution will be consistent

with the governing equations.

, then the solution is not unique. We can

add any constant temperature to the body and the solution will be consistent

with the governing equations.

We can also check the conditions under which a solution will exist for

this problem. Integrate the Poisson equation over  to get

to get

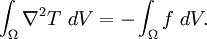

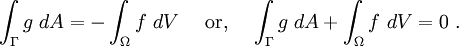

Apply the divergence theorem to the Laplacian. We get

From the boundary condition,

Therefore, we have

The boxed equation is called a compatibility condition and a solution does not exist unless this condition is satisfied.

In the context of the steady heat conduction problem, the compatibility condition says that the heat generated in the body must equal the heat flux. A similar (but more complicated) exercise can be used to show the existence and uniqueness of solutions for the full heat equation.

![\rho~C_v~\frac{\partial T}{\partial t} - \boldsymbol{\nabla} \bullet [\boldsymbol{\kappa}\bullet\boldsymbol{\nabla T]} = s~.](../I/m/2e6708f52b7f744ab16fb30da71d2b72.png)

![\text{(28)} \qquad

\int_{\Omega} \left(\rho~C_v~\frac{\partial T}{\partial t}\right)~w~dV -

\int_{\Omega} \left[\boldsymbol{\nabla} \bullet (\boldsymbol{\kappa}\bullet\boldsymbol{\nabla T)}\right]~w~dV =

\int_{\Omega} s~w~dV~.](../I/m/653d744af883caa8599e0da6439eaf9d.png)

![\text{(29)} \qquad

w\left[\boldsymbol{\nabla} \bullet (\boldsymbol{\kappa}\bullet\boldsymbol{\nabla} T)\right] =

\boldsymbol{\nabla} \bullet \left[w~(\boldsymbol{\kappa}\bullet\boldsymbol{\nabla} T)\right] -

(\boldsymbol{\nabla} w)\bullet(\boldsymbol{\kappa}\bullet\boldsymbol{\nabla} T) ~.](../I/m/d05d0735bfff3555fbde62af16ae8dde.png)

![\text{(30)} \qquad

\int_{\Omega} \left[\boldsymbol{\nabla} \bullet (\boldsymbol{\kappa}\bullet\boldsymbol{\nabla} T)\right]~w~dV =

\int_{\Omega} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \bullet \left[w~(\boldsymbol{\kappa}\bullet\boldsymbol{\nabla} T)\right]~dV

- \int_{\Omega} (\boldsymbol{\nabla} w)\bullet(\boldsymbol{\kappa}\bullet\boldsymbol{\nabla} T)~dV ~.](../I/m/86eef4ee3d8ec0efb234a5e684c06090.png)

![\text{(31)} \qquad

\int_{\Omega} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \bullet \left[w~(\boldsymbol{\kappa}\bullet\boldsymbol{\nabla} T)\right]~dV=

\int_{\Gamma} \left[w~(\boldsymbol{\kappa}\bullet\boldsymbol{\nabla} T)\right]\bullet\mathbf{n}~dA](../I/m/42d52e1e6afbc15fd35dd3ce9beffda4.png)

![\text{(32)} \qquad

\int_{\Omega} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \bullet \left[w~(\boldsymbol{\kappa}\bullet\boldsymbol{\nabla} T)\right]~dV=

\int_{\Gamma_q} \left[w~(\boldsymbol{\kappa}\bullet\boldsymbol{\nabla} T)\right]\bullet\mathbf{n}~dA~.](../I/m/d75a1702e0d545238032c4a597e11c48.png)

![\text{(33)} \qquad

\int_{\Omega} \left(\rho~C_v~\frac{\partial T}{\partial t}\right)~w~dV -

\int_{\Gamma_q} \left[w~(\boldsymbol{\kappa}\bullet\boldsymbol{\nabla} T)\right]\bullet\mathbf{n}~dA

+ \int_{\Omega} (\boldsymbol{\nabla} w)\bullet(\boldsymbol{\kappa}\bullet\boldsymbol{\nabla} T)~dV=

\int_{\Omega} s~w~dV~.](../I/m/6c6da7a9e544ac94cc5b4764a4989ac5.png)

![\text{(34)} \qquad

{

\int_{\Omega} \left(\rho~C_v~\frac{\partial T}{\partial t}\right)~w~dV +

\int_{\Omega} (\boldsymbol{\nabla} w)\bullet(\boldsymbol{\kappa}\bullet\boldsymbol{\nabla} T)~dV=

\int_{\Omega} s~w~dV +

\int_{\Gamma_q} \left[w~(\boldsymbol{\kappa}\bullet\boldsymbol{\nabla} T)\right]\bullet\mathbf{n}~dA~.

}](../I/m/59b5204bdb6da6ed196396b8f0269d96.png)

![\text{(37)} \qquad

{

\int_{\Omega} w~\left[\rho~C_v~T(0)\right]~dV =

\int_{\Omega} w~\left[\rho~C_v~T_0\right]~dV ~.

}](../I/m/7d73953dd942112f441cd85dad79fd9b.png)

![{

\begin{align}

& \mathsf{ Variational~ BVP ~for~ the ~Heat~ Equation}\\

& \\

\text{Find a function} & ~T(t) \in \mathcal{S}_t, t \in [0,\tau]

~\text{such that for all}~ w \in \mathcal{V}\\

& \\

& \int_{\Omega} \left(\rho~C_v~\frac{\partial T}{\partial t}\right)~w~dV +

\int_{\Omega} (\boldsymbol{\nabla} w)\bullet(\boldsymbol{\kappa}\bullet\boldsymbol{\nabla} T)~dV=

\int_{\Omega} s~w~dV -

\int_{\Gamma_q} w~\overline{q}~dA \\

& \int_{\Omega} w~\rho~C_v~T(0)~dV =

\int_{\Omega} w~\rho~C_v~T_0~dV ~.

\end{align}

}](../I/m/b0fe48d914e497488d66c68702675187.png)

![\nabla^2 (T+c) = \boldsymbol{\nabla} \bullet [\boldsymbol{\nabla (T+c)]} = \boldsymbol{\nabla} \bullet (\boldsymbol{\nabla T)} = \nabla^2 T~.](../I/m/8e969086eb7bafc961dfb1897b528849.png)

![\frac{\partial (T+c)}{\partial n} = [\boldsymbol{\nabla} (T+c)]\bullet\mathbf{n} = (\boldsymbol{\nabla} T)\bullet\mathbf{n}

= \frac{\partial T}{\partial n}](../I/m/c62ff83558dd60ce1d3aa05b0cd16efa.png)