Nonlinear finite elements/Overview of balance laws

< Nonlinear finite elementsGoverning equations in the deformed configuration

The governing equations for a continuum (apart from the kinematic relations and the constitutive laws) are

- Balance of mass

- Balance of linear momentum

- Balance of angular momentum

- Balance of energy

- Entropy inequality

Two important results from calculus

There are two important results from calculus that are useful when we use or derive these governing equations. These are

- The Gauss divergence theorem.

- The Reynolds transport theorem

These are useful enough to bear repeating at this point in the context of second order tensors.

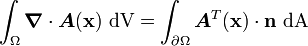

The Gauss divergence theorem

The divergence theorem relates volume integrals to surface integrals.

Let  be a body and let

be a body and let  be its boundary with outward unit normal

be its boundary with outward unit normal

. Let

. Let  be a second order tensor valued function of

be a second order tensor valued function of  . Then,

if

. Then,

if  is differentiable at least once (i.e.,

is differentiable at least once (i.e.,  ) then

) then

It is often of interest to consider the situation where  is not

continuously differentiable, i.e., when there are jumps in

is not

continuously differentiable, i.e., when there are jumps in  within the

body. Let

within the

body. Let  represent the set of surfaces internal to the

body where there are jumps in

represent the set of surfaces internal to the

body where there are jumps in  . In that case, the divergence theorem is

written as

. In that case, the divergence theorem is

written as

where the subscripts  and

and  represents the values on the two sides of

the jump discontinuity with normal

represents the values on the two sides of

the jump discontinuity with normal  .

.

Reynold's transport theorem

The transport theorem shows you how to calculate the material time derivative of an integral. It is a generalization of the Leibniz formula.

Let  be a body in its current configuration and let

be a body in its current configuration and let  be

its surface. Also, let

be

its surface. Also, let  .

.

If  is a scalar valued function of

is a scalar valued function of  and

and  then

then

If  is a vector valued function of

is a vector valued function of  and

and  .

Then

.

Then

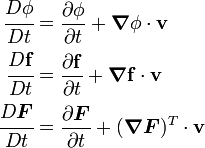

To refresh your memory, recall that the material time derivative is given by

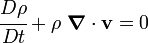

Conservation of mass

For the situation where a body does not gain or lose mass, the balance of mass is written as

Sometimes, this equation is also written in conservative form as

If the material is incompressible then the density does not change with time and we get

For Lagrangian descriptions we can show that

where  is the initial density.

is the initial density.

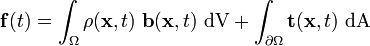

Conservation of linear momentum

The balance of linear momentum is essentially Newton's second applied to continua. Newton's second law can be written as

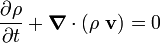

where the linear momentum  is given by

is given by

and the total force  is given by

is given by

where  is the density,

is the density,  is the spatial velocity,

is the spatial velocity,  is

the body force and

is

the body force and  is the surface traction. Therefore, the balance

of linear momentum can be written as

is the surface traction. Therefore, the balance

of linear momentum can be written as

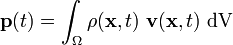

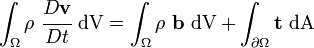

Now using the transport theorem, we have

From the conservation of mass, the second term on the right hand side is zero and we are left with

Therefore, the balance of linear momentum can be written as

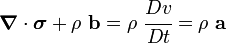

Using Cauchy's theorem ( ) and the divergence theorem we

can show that the balance of linear momentum can be written as

) and the divergence theorem we

can show that the balance of linear momentum can be written as

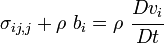

In index notation,

Conservation of angular momentum

We also have to make sure that the moments are balanced. This requirement takes the form of the conservation of angular momentum and can be written as

We can show that this equation reduces down to the requirement that the Cauchy stress is symmetric, i.e.,

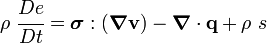

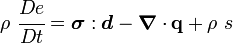

Conservation of energy

The balance of energy can be expressed as

where  is the internal energy per unit mass,

is the internal energy per unit mass,  is the heat flux vector

and

is the heat flux vector

and  is the heat source per unit volume.

is the heat source per unit volume.

We may also write this equation as

where  , the rate of deformation tensor, is the symmetric part of the

velocity gradient. We can do this because the contraction of the skew

symmetric part of the velocity gradient with the symmetric Cauchy stress gives

us zero.

, the rate of deformation tensor, is the symmetric part of the

velocity gradient. We can do this because the contraction of the skew

symmetric part of the velocity gradient with the symmetric Cauchy stress gives

us zero.

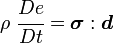

For purely mechanical problems,  and

and  . So we can write

. So we can write

This shows that  and

and  are conjugate in power.

are conjugate in power.

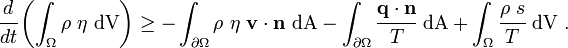

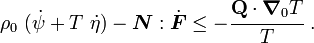

Entropy inequality

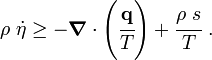

The entropy inequality is useful in determining which forms of the constitutive equations are admissible. This inequality is also called the dissipation inequality. In its Clausius-Duhem form, the inequality may written as

where  is the specific entropy (entropy per unit mass) and

is the specific entropy (entropy per unit mass) and  is the

temperature.

is the

temperature.

In differential form the Clausius-Duhem inequality can be written as

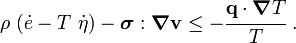

In terms of the specific internal energy, the entropy inequality can be expressed as

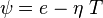

If we define the Helmholtz free energy (the energy that is available to do mechanical work) as

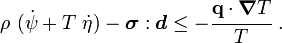

we can also write,

Governing equations in the reference configuration

The Lagrangian form of the governing equations can be obtained using the relations between the various measures in the deformed and reference configurations.

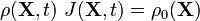

Balance of mass

The Lagrangian form of the balance of mass is

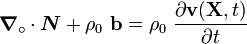

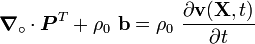

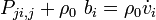

Balance of linear momentum

The Lagrangian form of the balance of linear momentum is

where  is the nominal stress and

is the nominal stress and  indicates that the

derivatives are with respect to

indicates that the

derivatives are with respect to  . In terms of the first Piola-Kirchhoff

stress

. In terms of the first Piola-Kirchhoff

stress  we can write

we can write

In index notation,

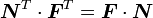

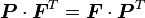

Balance of angular momentum

The balance of angular momentum in Lagrangian form is

In terms of the first Piola-Kirchhoff stress

In terms of the second Piola-Kirchhoff stress

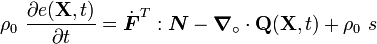

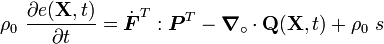

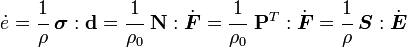

Balance of energy

In the material frame, the balance of energy takes the form

where  is the heat flux per unit reference area.

is the heat flux per unit reference area.

In terms of the first Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor we have

Entropy inequality

The entropy inequality in Lagrangian form is

In terms of the first P-K stress we have

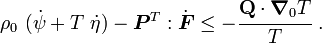

Conjugate work measures

Whatever measures we choose to use to represent stress and strain (or a rate of strain), their product should give us a measure of the work done (or the power spent). This measure should not depend on the chosen measures.

Therefore, the correct combination of stress and strain should be work conjugate or power conjugate. Three commonly used power conjugate stress and rate of strain measures are

- The Cauchy stress (

) and the rate of deformation (

) and the rate of deformation ( ).

). - The nominal stress (

) and the rate of the deformation gradient (

) and the rate of the deformation gradient ( ).

). - The second P-K stress (

) and the rate of the Green strain (

) and the rate of the Green strain ( ).

).

We can show that, in the absence of heat fluxes and sources,

Many more work/power conjugate measures can be found in the literature.

![\int_{\Omega} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \boldsymbol{A}~\text{dV} = \int_{\partial \Omega} \boldsymbol{A}^T\cdot\mathbf{n}~\text{dA} +

\int_{\partial \Omega_{\text{int}}} \left[\boldsymbol{A}^T_{+} - \boldsymbol{A}^T_{-}\right]\cdot\mathbf{n}_{+}~\text{dA}](../I/m/5b9dce0b01b0d36cdeab1cb564901d32.png)

![\cfrac{D}{Dt}\left[\int_{\Omega} \phi(\mathbf{x},t)~\text{dV}\right] =

\int_{\Omega} \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial t}~\text{dV} + \int_{\partial \Omega} (\mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{n})~\phi~\text{dA} =

\int_{\Omega} \left[\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial t} + \boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \left( \phi~\mathbf{v}\right) \right]~\text{dV}](../I/m/cf6f8b1622e95aeef193575ba6bcce76.png)

![\cfrac{D}{Dt}\left[\int_{\Omega} \mathbf{f}(\mathbf{x}, t)~\text{dV}\right] =

\int_{\Omega} \frac{\partial \mathbf{f}}{\partial t}~\text{dV} + \int_{\partial \Omega} (\mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{n})~\mathbf{f}~\text{dA} =

\int_{\Omega} \left[\frac{\partial \mathbf{f}}{\partial t} + \boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot (\mathbf{f}\otimes\mathbf{v})\right]~\text{dV}](../I/m/f7fdafcd1d701d00229e5d2bedcce1c3.png)

![\cfrac{D}{Dt}\left[\int_{\Omega} \rho(\mathbf{x},t)~\mathbf{v}(\mathbf{x},t)~\text{dV}\right] =

\int_{\Omega} \rho(\mathbf{x},t)~\mathbf{b}(\mathbf{x},t)~\text{dV} + \int_{\partial \Omega} \mathbf{t}(\mathbf{x},t)~\text{dA}](../I/m/fa07d2c66b5dddb49f6ffebcb1e49b0e.png)

![\cfrac{D}{Dt}\left[\int_{\Omega} \rho~\mathbf{v}~\text{dV}\right] =

\int_{\Omega} \left[\rho~\cfrac{D\mathbf{v}}{Dt} +

\left(\cfrac{D\rho}{Dt} + \rho~\boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \mathbf{v}\right)\right]~\text{dV}](../I/m/e8b54eaae3dbd3cab1ae8b5bd7cf930f.png)

![\cfrac{D}{Dt}\left[\int_{\Omega} \rho(\mathbf{x},t)~\mathbf{v}(\mathbf{x},t)~\text{dV}\right] =

\int_{\Omega} \rho~\cfrac{D\mathbf{v}}{Dt}~\text{dV}](../I/m/cd3bbba33ba0e1a68cfe92e0a1334d4d.png)

![\cfrac{D}{Dt}\left[\int_{\Omega} \mathbf{x} \times (\rho~\mathbf{v})~\text{dV}\right] =

\int_{\Omega} \mathbf{x} \times (\rho~\mathbf{b})~\text{dV} + \int_{\partial \Omega} \mathbf{x} \times \mathbf{t}~\text{dA}](../I/m/7b620d41088986a7029fca016d18e0e9.png)