Motivation and emotion/Book/2015/Running and depression

< Motivation and emotion < Book < 2015What role can running play in the treatment of depression?

|

|

Overview

|

We all know running is great for our physical health. It lowers our blood pressure, increases oxygen saturation in our lungs, helps regulate our heart beat, encourages the building of muscle tissue, increases bone density and helps to ward off many preventable lifestyle diseases like cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes (Lee et al., 2014). But what effect can it have on the mental well-being for those suffering depression?

With an estimated one in every six people suffering depression in their lifetime, it is now the most commonly diagnosed mental disorder worldwide (Beyond Blue, 2015). In Australia, this means that in 2015 alone, over one million people have or will suffer from depression (Beyond Blue, 2015). This illness is clearly on the rise, and many sufferers seek a variety of treatment options, including Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Antidepressant medication which have been the focus of most research. However, although a relationship between running and mood has long been established, the use of running as a form of treatment for depression has only recently generated research (Brosse, Sheets, Lett & Blumenthal, 2002). So could running have an impact on this chronic, anhedonic disease? Let's take a look... |

What is depression?

Depression is a mood, characterised by low affect, often accompanied by feelings of emptiness and isolation (see Figure 1), hopelessness, anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure), a loss of energy, difficulty sleeping, changes in weight and eating patterns, diminished concentration, reduced appetite and sometimes self-harm behaviours or suicide (Brosse et al., 2002).

We can all feel sad or upset at times, however depression is an enduring condition often lasting weeks, months or even years, which disturbs an individual's daily functioning and well-being (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Depression is not simply a fleeting feeling of sadness but rather a pervasive and relentless sense of despair, which often leads sufferers to feel this state is inescapable (Brosse et al., 2002).

This mood is characteristic of many diagnosable psychiatric disorders as defined in the DSM-V including: Major Depressive Disorder, Persistent Depressive Disorder, Seasonal Affective Disorder and Manic Depression (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

What causes depression?

Although many people suffer from depression the exact underlying cause still remains largely unknown (Martinsen, 1987). However a few factors appear to contribute:

- Life events - Depression often stems from rumination on sadness (Bonanno, Goorin & Coifman, 2008). Stressful or difficult times could trigger this mood or disorder as individuals focus on the distressing outcome and consequently slip into this state.

- Neurochemical factors - A number of brain changes are associated with individuals suffering depression. Reduced hippocampal size, an imbalance or low level of particular neurotransmitters and an excess of cortisol all contribute to depression (Martinsen, 1987).

- Negative attributional style and personality factors - Certain types of personalities and cognitive styles could also lead to the development of depression (Hewitt, Flett & Ediger, 1996). Individuals who are perfectionists or people who are very critical of themselves are at particularly high risk (Hewitt et al., 1996).

- Genetic factors - Depression has also been shown to run in families which suggests individuals could be genetically predisposed to the disorder (Bonanno et al., 2008).

Some of these factors are encompassed in psychological models of depression which we will discuss later in this chapter.

The clinical diagnosis of depression is predominantly analysed by a psychologist according to the DSM-V guidelines, however General Practitioners will often determine if there is a need to refer an individual based on the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale which requires individuals to rate their agreeance with 42 items (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

What is running?

Running is a weight-bearing aerobic exercise in which oxygen is metabolised to produce energy (Brosse et al., 2002). It is characterised by a flight phase in the gait cycle where both of the runner's feet are not in contact with the ground (as can be seen in Figure 2). This is different from walking where one foot is always in contact with the ground. It is typically conducted at a pace slightly faster than the individual's walking speed.

So really... People have been running since we've had two legs (Greist et al., 1979)! It's an activity that comes naturally to us which means no matter how fast or slow you go, almost everyone is a runner at heart.

What are the benefits of running?

Running has loads of physical benefits:

- Reduces the risk of many preventable lifestyle diseases (eg. Type II Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease and Obesity)

- Increases bone density (prevents osteoporosis)

- Increases oxygen saturation in our lungs (Martinsen, Medhus & Sandvik 1985)

- Reduces resting heart rate (Doyne et al., 1987)

- Increases cardiac output (amount of blood pumped out of the heart each minute) (Doyne et al., 1987)

- Weight loss (Griest et al., 1979)

But it also has several important psychological benefits:

- Relieves stress (Chaouloff, 1989)

- Improves self-esteem (Greist et al., 1979)

- Improves concentration

- Regulates sleep patterns

- Boosts mood (Brosse et al., 2002)

Since runners subjectively experience elevation of mood, does this mean it could help sufferers of depression who have low affect?

But before we answer this, it's time to see what you've learnt so far!

Check your knowledge |

Running as a therapy

Efficacy of running in reducing depression

Regular running has been associated with lower scores on depression questionnaires (Brosse et al., 2002), but what empirical evidence is there to support the idea of running as a therapy? Research so far shows......

|

FOR:

|

AGAINST:

|

Looking at the above table, although there are some non-supporting studies, the majority find supporting evidence for the use of running as a therapy for people suffering depression.

Weighing it all up

Benefits of running as a therapy

- Low cost compared to psychotherapies (Brosse et al., 2002; Kruisdijk, Hendricksen, Tak, Beekman & Hopman-Rock, 2012).

- Less social stigma for sufferers than other types of psychotherapies or pharmacotherapy (Refer Figure 3, Brosse et al., 2002).

- Minimal dangerous side effects unlike many pharmacotherapy options (Kruisdijk et al., 2012; Martinsen,1987).

- Can be used in combination with other methods (Kruisdijk et al., 2012; Martinsen, 1987).

Challenges of running as a therapy

- It can be hard to motivate depressed individuals to run, especially when they already struggle to find motivation to complete everyday tasks (Martinsen, 2008; Kruisdijk et al., 2012).

- Running is a lifestyle intervention (Kruisdijk et al., 2012). According to the transtheoretical model of behaviour change, it can be difficult to make this lifestyle transformation to your everyday life (Brosse et al., 2002). The individual must contemplate the activity and prepare themselves for action before running can start to be maintained as a therapy (Kruisdijk et al., 2012).

- Injury can cause loss of motivation in individuals and deter them from continuing the therapy (Kruisdijk et al., 2012)

Why does running work as a therapy for depression?

So now we can see that running has an impact on depression but why? Let's see what psychological theories say....

Note: This section does not cover all theoretical models of depression, only those which are applicable to running. Consequently, many important cognitive models and models which attribute depression to a multitude of factors (for example the biopsychosocial model) have been excluded for this reason.

Running could serve as an alternative outlet for this anger and aggression, directing it away from the self (Weinstein & Meyers, 1983). In this way it could reduce the discrepancy between the id (unconscious mind) and ego, by channelling the anger in a socially acceptable way, thus alleviating the negative feelings of self-dislike in the individual.

Additionally, this leads to improved self-esteem as running in this model makes the individual aware of their limitations and helps to develop self-discipline that replaces the unconscious repressed anger (Weinstein & Meyers, 1983).

Psychodynamic model

Although largely outdated nowadays, the psychodynamic model was one of the first well recognised theories of depression (Weinstein & Meyers, 1983). In this model, depression is proposed to stem from a perceived loss of either an object, person or goal. A discrepancy arises when the conscious mind (ego) recognises that the loss is no longer able to be attained (Newman & Hirt, 1983). This reduces the self-esteem in an individual as the loss cannot be regained. In an attempt to repress this uncomfortable feeling of inadequacy, the anger over the missed opportunity is directed towards the self (Weinstein & Meyers,1983). According to psychodynamic theory, this inwards direction of anger is the cause of depression (Newman & Hirt, 1983).

The improvements in mood following running could be attributed to the achievement of having accomplished a run becoming a positive reinforcer in itself (Weinstein & Meyers, 1983).

Furthermore, this in turn increases self-esteem as the individual gains sustained reinforcement for running and feels proud of themselves. According to this model, the increase in reinforcers and reassurance of coping skills, reduces depression in individuals (Weinstein & Meyers, 1983). Additional secondary reinforcers like losing weight and promoting social interactions may further encourage continuation of running and a more positive self-image so assisting to combat depression.

Behavioural model

In a move away from processes in the unconscious mind, a focus on observable behaviour arose, with behaviourists suggesting that dysfunctional maladaptive behaviours leading to depression were in fact learned processes (Weinstein & Meyers, 1983). The most predominant behavioural model is Lewinshon’s theory, in which a discontinuation in receiving positive reinforcement from the environment and a lack of social support, drive depression (Lewinshon, 1974). Those who develop depression often have ineffective coping strategies for dealing with this lack of positive reinforcement and when coupled with a greater sense of self awareness of this coping deficit, can lead to social withdrawal (Lewinshon, 1974).

Cognitive-behavioural models

These models attempted to integrate important cognitive processes (thinking and feeling) into the framework of learning theory (the basis of the behavioural model). The cognitive-behavioural model proposes that depression is the result of learned maladaptive cognitions which manifest in distorted thoughts and inaccurate judgements (Martinsen, 2008). This pessimistic thinking style leads depressed people to perceive situations negatively (Pearsons & Miranda, 1992).

Running is proposed to result in disruption to these ruminations of negative events as well as improving the individuals’ maladaptive belief system (Danielsson et al., 2013).

This is achieved by restructuring the individual’s self perceptions, by empowering them to make positive internal attributions of their running achievements and improvement - seeing themselves in a more positive light, can lead them to see the world and their future in a more positive way too (Weinstein & Meyers, 1983).

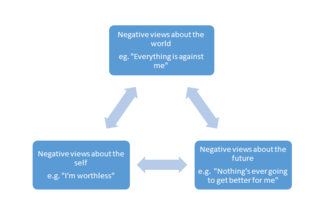

Beck's negative cognitive triad

Beck’s theory highlights the tendency of depressed individuals to have negative thoughts originating from dysfunctional beliefs about how they view themselves, the world and the future (1970, as cited in Pearsons & Miranda, 1992). The stronger these pessimistic thoughts, the more severe the individual's depression (see Figure 4).

These negative schemas distort depressed people's perception of events and predispose them to cognitive biases so reinforcing their pessimistic views (Pearsons & Miranda, 1992).

Running is hypothesised to foster a sense of self efficacy in the individual (Doyne et al., 1987). This may teach them that they are not “helpless” to all life events and can exert control over certain aspects of their lives, like their fitness. Over time, this deeply rooted belief is broken and their depressive symptoms alleviated (Doyne et al., 1987).

Seligman's learned helplessness

Seligman noted that depressed individuals have a pessimistic attributional style which emphasises the fact that they have little control over their environments and view any efforts to try and increase control as pointless (1974, as cited in Pearsons & Miranda, 1992). This sense of hopelessness makes individuals believe they are responsible for the negative life events and overgeneralise their weaknesses to everything they do (Pearsons & Miranda, 1992).

Biochemical models

Depression over recent years has increasingly been recognised to have biochemical roots with sufferers shown to have particular neurological differences to non-depressed individuals (Martinsen, 1987). This has lead to the increased importance of recognising the brain chemistry of individuals with depression, and consequently the development of several important theories behind the causal nature of depression.

Perhaps this is where running could fit in, with some studies showing that it produces significant increases in monoamine levels (Chaouloff, 1989). Running has been specifically noted to increase dopamine synthesis and metabolism (Chaouloff, 1989).These findings though, are still only preliminary.

It is also suggested that running boosts serotonin levels which increase activity in the hippocampus, perhaps this could be another reason why running shows such positive effects on depression sufferers (Chaouloff, 1989).

Monoamine hypothesis

This theory acknowledges a deficit in certain monoamines in the brain such as norepinephrine (noradrenaline), dopamine and serotonin in individuals with depression (Roy & Campbell, 2013). However, this imbalance varies between sufferers with some showing deficits in several of these monoamines and others showing none (Pearson & Miranda, 1992).

Furthermore, as you'll recall from earlier in this chapter individuals with depression also have a smaller

hippocampus than non-depressed individuals. Monoamines have been linked to increasing activity in the hippocampus (Chaouloff, 1989). So in this theory, finding a way to increase monoamine levels should also

reduce depressive symptoms (Roy & Campbell, 2013).

Running stimulates the pituitary gland to release these hormones, so boosting mood in runners (Chaouloff, 1989). This has been termed colloquially as a "runner's high". This endorphin rush could improve depressed individual's affect in the short-term and continue if they are engaging in regular runs. It has been proposed that perhaps this elevated mood could have a long term effect on the brain, but this is yet to be supported by research (Chaouloff, 1989). Maybe this is why running has been demonstrated to benefit depression sufferers.

Endorphins

Although not formulated into a psychological theory of depression as yet, endorphins are the happy, feel-good chemicals in your brain which are released by the pituitary gland (Chaouloff, 1989).

Endorphins aid to boost mood and also have many motivating aspects (Chaouloff, 1989). They are also suggested to reduce perception of pain (Chaouloff, 1989). How this links to depression is unclear, but if endorphins are able to be increased in depressed individuals then would their low affect be improved?

Conclusion

Overall, running has been shown to have some really positive effects on both physical and mental health of sufferers of depression (see Figure 5). However, despite the research suggesting running could be used as a therapy, studies still leave many questions unanswered.

How long? How fast? How often? And how far? These are just some areas future randomised controlled studies should look at investigating to test the true effect of running on depression.

More research also needs to be directed towards investigating the causal mechanism behind why running works as a treatment for depression. Although we have investigated several models in this chapter, the real reason for this antidepressant effect of running remains largely unknown.

The positives of running for depressed individuals seem to outweigh the negatives. So it is suggested running should be used in conjunction with other therapies until more research clarifies its application as a therapy.

|

So if you know of someone suffering from depression, why not encourage them to read this chapter? Running could be an intervention suited to them, to help alleviate their depression! But now it's time for YOU to fire up that energy-producing, oxygen-delivering, bone-strengthening process we call running! As it could not only get you in better shape but also improve your mental well-being.

|

See also

- Exercise and mood (Book chapter, 2014)

- Exercise and motivation (Book chapter, 2015)

- Depression and motivation (Book chapter, 2014)

- Major depressive episodes and motivation (Book chapter, 2015)

- Depression in athletes (Book chapter, 2014)

References

Babyak, M., Blumenthal, J. A., Herman, S., Khatri, P., Doraiswamy, M., et al. (2000). Exercise treatment for major depression: maintenance of therapeutic benefit at 10 months. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62(5), 633-638. Retrieved from: https://www.madinamerica.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Exercise%20treatment%20for%20major%20depression.pdf

Beyond Blue. (2015). The facts about Depression. Retrieved from: https://www.beyondblue.org.au/the-facts

Blumenthal, J. A., Babyak, M. A., Doraiswamy, P. M., Watkins, L., Hoffman, B. M., et al. (2007). Exercise and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69(7), 587-596. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318148c19a

Blumenthal, J. A., Babyak, M. A., Moore, K. A., Craighead, W. E., Herman, S., et al. (1999). Effects of exercise training on older patients with major depression. Archives of Internal Medicine, 159(19), 2349-2356. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.19.2349

Bonanno, G. A., Goorin, L., & Coifman, K. G. (2008). Sadness and grief. Handbook of Emotions, 3, 797-806. Retrieved from: http://raulkoffman.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Handbook-of-Emotions.pdf#page=813

Brosse, A.L., Sheets, E.S., Lett, H.S., & Blumenthal, J.A. (2002). Exercise and the Treatment of Clinical Depression in Adults: Recent Findings and Future Directions. Sports Medicine, 32(12), 741-760. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200232120-00001

Chaouloff, F. (1989). Physical exercise and brain monoamines: a review. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 137(1), 1-13. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1989.tb08715.x

Danielsson, L., Noras, A. M., Waern, M., & Carlsson, J. (2013). Exercise in the treatment of major depression: A systematic review grading the quality of evidence. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 29(8), 573-585. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2013.774452

Doyne, E. J., Ossip-Klein, D. J., Bowman, E. D., Osborn, K. M., McDougall-Wilson, I. B., & Neimeyer, R. A. (1987). Running versus weight lifting in the treatment of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55(5), 748. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.55.5.748

Dunn, A. L., Trivedi, M. H., Kampert, J. B., Clark, C. G., & Chambliss, H. O. (2005). Exercise treatment for depression: Efficacy and dose response. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(1), 1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.003

Foley, L. S., Prapavessis, H., Osuch, E. A., De Pace, J. A., Murphy, B. A., & Podolinsky, N. J. (2008). An examination of potential mechanisms for exercise as a treatment for depression: a pilot study. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 1(2), 69-73. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2008.07.001

Fremont, J., & Craighead, L. W. (1987). Aerobic exercise and cognitive therapy in the treatment of dysphoric moods. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 11(2), 241-251. doi: 10.1007/BF01183268

Greist, J. H., Klein, M. H., Eischens, R. R., Faris, J., Gurman, A. S., & Morgan, W. P. (1979). Running as treatment for depression. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 20(1), 41-54. doi:10.1016/0010-440X(79)90058-0

Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., & Ediger, E. (1996). Perfectionism and depression: Longitudinal assessment of a specific vulnerability hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105(2), 276-280. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.105.2.276

Hoffman, B. M., Babyak, M. A., Craighead, W. E., Sherwood, A., Doraiswamy, P. M., Coons, M. J., & Blumenthal, J. A. (2011). Exercise and pharmacotherapy in patients with major depression: one-year follow-up of the SMILE study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 73(2), 127-133. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820433a5

Klein, M. H., Greist, J. H., Gurman, A. S., Neimeyer, R. A., Lesser, D. P., Bushnell, N. J., & Smith, R. E. (1984). A comparative outcome study of group psychotherapy vs. exercise treatments for depression. International Journal of Mental Health, 148-176. Retrieved from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41344367

Kruisdijk, F. R., Hendriksen, I. J., Tak, E. C., Beekman, A. T., & Hopman-Rock, M. (2012). Effect of running therapy on depression (EFFORT-D). Design of a randomised controlled trial in adult patients [ISRCTN 1894]. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 50-59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-50

Lee, D., Pate, R. R., Lavie, C. J., Sui, X., Church, T. S., & Blair, S. N. (2014). Leisure-Time Running Reduces All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality Risk. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 64(5), 472-481. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.058

Lewinsohn, P. M. (1974). A behavioral approach to depression: Contemporary theory and research. Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons. Retrieved from: http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/1975-07556-006

Martinsen, E. W. (1987). The role of aerobic exercise in the treatment of depression. Stress Medicine, 3(2), 93-100. doi: 10.1002/smi.2460030205

Martinsen, E. W. (2008). Physical activity in the prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 62(sup47), 25-29. doi: 10.1080/08039480802315640

Martinsen, E. W., Medhus, A., & Sandvik, L. (1985). Effects of aerobic exercise on depression: a controlled study. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 291(6488), 109. Retrieved from: http://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/291/6488/109.full.pdf

McCann, I. L., & Holmes, D. S. (1984). Influence of aerobic exercise on depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(5), 1142-1147. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.46.5.1142

Newman, R. S., & Hirt, M. (1983). The psychoanalytic theory of depression: Symptoms as a function of aggressive wishes and level of field articulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 92(1), 42-48. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.92.1.42

Persons, J. B., & Miranda, J. (1992). Cognitive theories of vulnerability to depression: Reconciling negative evidence. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 16(4), 485-502. doi: 10.1007/BF01183170

Pilu, A., Sorba, M., Hardoy, M. C., Floris, A. L., Mannu, F., et al. (2007). Efficacy of physical activity in the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorders: preliminary results. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health: CP & EMH, 3(1), 8. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-3-8

Roy, A., & Campbell, M. K. (2013). A unifying framework for depression: bridging the major biological and psychosocial theories through stress. Clinical & Investigative Medicine, 36(4), 170-190. Retrieved from: http://cimonline.ca/index.php/cim/article/view/19951/16474

Tomporowski, P. D., & Ellis, N. R. (1984). Effects of exercise on the physical fitness, intelligence, and adaptive behavior of institutionalized mentally retarded adults. Applied Research in Mental Retardation, 5(3), 329-337. doi: 10.1016/S0270-3092(84)80054-5

Trivedi, M. H., Greer, T. L., Church, T. S., Carmody, T. J., Grannemann, B. D., et al. (2011). Exercise as an augmentation treatment for nonremitted major depressive disorder: a randomized, parallel dose comparison. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72(5), 677-684. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06743

Veale, D., Le Fevre, K., Pantelis, C., de Souza, V., Mann, A., & Sargeant, A. (1992). Aerobic exercise in the adjunctive treatment of depression: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 85(9), 541-544. doi:10.1177/014107689208500910

Weinstein, W. S., & Meyers, A. W. (1983). Running as treatment for depression: is it worth it. Journal of Sport Psychology, 5(3), 288-301. Retrieved from: http://www.humankinetics.com/acucustom/sitename/Documents/DocumentItem/8847.pdf

External links

Click this link for an individual's personal perspective on how running helped their recovery from depression.

Looking for tips on correct running technique? Look at this page

Looking for more information about upcoming running events in Australia? Check out this site!

If you or someone you know feels any distress or just needs to talk, please utilise the following links: