Minerals/Metals

< Minerals

Metals constitute a large portion of the Periodic Table of elements. Their combinations with each other and the other elements result in the minerals that compose rocky-objects.

Generally, the transition metals constitute the periodic table of elements from groups 3-12, beginning with scandium (Sc) and ending with element number 112 Copernicium.

Usually, these and the other metals are divided into several subgroups for specific purposes:

- Metalloids - gallium (Ga) through selenium (Se) and cadmium (Cd) through tellurium (Te).

- Alkaline earth metals - group 2: beryllium (Be) through radium (Ra).

- Alkali metals - group 1: lithium (Li) through francium (Fr).

- Body-centered cubic metals - titanium (Ti) through chromium (Cr), zirconium (Zr) through molybdenum (Mo), and hafnium (Hf) through tungsten (W).

- Heavy metals - mercury (Hg) through polonium (Po).

- Lanthanides - lanthanum (La) through lutetium (Lu), also called the rare-earths.

- Precious metals - ruthenium (Ru) through silver (Ag) and rhenium (Re) through gold (Au).

- Siliconides.

- Transition metals are often restricted to manganese (Mn), iron (Fe), cobalt (Co), nickel (Ni), copper (Cu), and zinc (Zn).

- Transuranics - neptunium (Np) through Roentgenium (Rg) and Copernicium (Cn).

The category of metals also includes aluminum, scandium (Sc), yttrium (Y), technetium (Tc), and the actinides.

Crystals

In general the close-packing structures: face-centered cubic (fcc) and hexagonal close-packed (hcp) are the most efficient way to pack a bunch of hard, equal-sized marbles into the smallest space. Metals often occur in these structures and as body-centered cubics which are not close-packed structures.

Actinide minerals

"Uranophane Ca(UO2)2(SiO3OH)2·5H2O is a rare calcium uranium [nesosilicate] hydrate mineral that forms from the oxidation of uranium bearing minerals. Uranophane is also known as uranotile. It has a yellow color and is radioactive."[1]

Def. any "of the 14 radioactive elements of the periodic table that are positioned under the lanthanides to which they have similar chemistry"[2] is called an actinide in inorganic chemistry.

Alkali metal minerals

The alkali metals are from group 1 of the Periodic Table and include hydrogens.

Alkaline earth metal minerals

.png)

Barium is bcc (α-Ba) at room temperature as the phase diagram on the left indicates. It does change to an hcp structure at high pressures and temperatures.

Native barium is not known to occur on the surface of the Earth.

Def. any "oxide of the elements of group II of the periodic table; they are not as basic as the alkalis, and not so soluble in water"[3] is called an alkaline earth.

Def. any "of the elements of group II of the periodic table; they are low-density metals that react readily with water to form strongly basic hydroxides, and with many acids to form salts"[4] is called an alkaline earth metal.

Aluminide minerals

The aluminides are those naturally occurring minerals with a high atomic % aluminum.

In the image on the right of a flake of native aluminum, the scale bar = 1 mm.

"Aluminium is the third most abundant element (after oxygen and silicon) in the Earth's crust, and the most abundant metal there. It makes up about 8% by mass of the crust, though it is less common in the mantle below."[5]

Def. any "intermetallic compound of aluminium and a more electropositive element"[6] is an aluminide in chemistry.

Body-centered cubic metal minerals

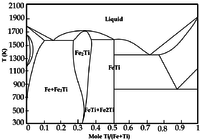

"Microbeam analysis of eclogites from the ultrahigh-pressure metamorphic belt in Dabieshan, China has revealed native titanium inclusions in garnets of coesite eclogite. The inclusions are about 10 μm in size, have a submetallic luster from the thin oxidation film on the surface, and are brown under reflected light."[7]

Titanium "undergoes a phase transformation (hcp to bcc) at 882 °C [5]."[8]

As the phase diagram on the left indicates, there is a miscibility gap between bcc iron (α-Fe) and hcp (α-Ti) up to about 800°C.

Carbonide minerals

"The mineral Lonsdaleite is a translucent, brownish yellow and is made from the atoms of carbon but the arrangement of these atoms is different from the arrangement of carbon atoms in a diamond. [...] The mineral is very rare and is formed naturally whenever [...] graphite containing meteorites fall on the earth and hit the surface."[9]

"Found in the Canyon Diablo and Goalpara meteorites."[10]

Def. any

- "binary compound of carbon and a more electropositive element",[11]

- the "polyatomic ion C22−, or any of its salts",[12]

- the "monatomic ion C4−, or any of its salts",[12]

- a "carbon-containing alloy or doping of a metal or semiconductor, such as steel",[12]

- an archaic form of carbide,[13] or

- naturally occurring minerals composed of 50 atomic percent, or more, carbon,

are called carbonides.

Def. minerals with greater than 25 at % carbon but less than 50 at % carbon are called carbonide-like minerals.

Chalcogen minerals

In the magnified image of the sample on the right are native selenium needles.

Def. any "element of group 16 of the periodic table"[14] is called a chalcogen in inorganic chemistry.

Metalloids

Native arsenic such as in the image on the right occurs in silver ore veins.

Def. an "element [...] intermediate in properties between that of a metal and a nonmetal; especially one that exhibits the external characteristics of a metal, but behaves chemically more as a nonmetal"[15] is called a metalloid.

Precious metal minerals

Precious metals are usually rare, chemically relatively inert, and often colorful.

They are transition metals ruthenium (Ru) through silver (Ag) and rhenium (Re) through gold (Au).

Transition metal minerals

The most advantageous form for copper is native copper.

On the right is a large, sculptural specimen of penny-bright copper from Arizona.

Transuranic minerals

"Based on the observation of the long-lived isotopes of roentgenium, 261Rg and 265Rg (Z = 111, t1/2 ≥ 108 y) in natural Au, an experiment was performed to enrich Rg in 99.999% Au. 16 mg of Au were heated in vacuum for two weeks at a temperature of 1127°C (63°C above the melting point of Au). The content of 197Au and 261Rg in the residue was studied with high resolution inductively coupled plasma-sector field mass spectrometry (ICP-SFMS). The residue of Au was 3 × 10−6 of its original quantity. The recovery of Rg was a few percent. The abundance of Rg compared to Au in the enriched solution was about 2 × 10−6, which is a three to four orders of magnitude enrichment."[16]

Research

Hypothesis:

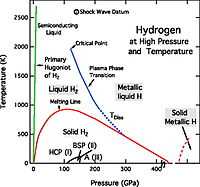

- Other elements can occur in the metal-like structures as molecules.

Control groups

The findings demonstrate a statistically systematic change from the status quo or the control group.

“In the design of experiments, treatments [or special properties or characteristics] are applied to [or observed in] experimental units in the treatment group(s).[17] In comparative experiments, members of the complementary group, the control group, receive either no treatment or a standard treatment.[18]"[19]

Proof of concept

Def. a “short and/or incomplete realization of a certain method or idea to demonstrate its feasibility"[20] is called a proof of concept.

Def. evidence that demonstrates that a concept is possible is called proof of concept.

The proof-of-concept structure consists of

- background,

- procedures,

- findings, and

- interpretation.[21]

See also

References

- ↑ "Uranophane, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. February 28, 2013. Retrieved 2013-05-08.

- ↑ SemperBlotto (31 May 2005). "actinide, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ↑ SemperBlotto (18 February 2007). "alkaline earth, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ↑ SemperBlotto (18 February 2007). "alkaline earth metal, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ↑ "Aluminium, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 28 October 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- ↑ SemperBlotto (21 February 2007). "aluminide, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ↑ Jing Chen, Jiliang Li, and Jun Wu (30 April 2000). "Native titanium inclusions in the coesite eclogites from Dabieshan, China". Earth and Planetary Science Letters 177 (3-4): 237-40. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(00)00057-1. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0012821X00000571. Retrieved 2015-08-19.

- ↑ B.B. Panigrahi, M.M. Godkhindi , K. Das, P.G. Mukunda, and P. Ramakrishnan (15 April 2005). "Sintering kinetics of micrometric titanium powder". Materials Science and Engineering: A 396 (1-2): 255-62. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2005.01.016. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921509305000778. Retrieved 2015-08-19.

- ↑ payam (30 July 2013). "Top 10 Hardest Material in the world". Help Tips. Retrieved 2015-07-30.

- ↑ Willard Lincoln Roberts, George Robert Rapp, Jr., and Julius Weber (1974). Encyclopedia of Minerals. 450 West 33rd Street, New York, New York 10001 USA: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company. pp. 121-2. ISBN 0-442-26820-3.

- ↑ "carbide, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 23 January 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- 1 2 3 Paul G (3 January 2006). "carbide, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ↑ Equinox (24 November 2011). "carbonide, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ↑ SemperBlotto (28 September 2005). "chalcogen, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ↑ SemperBlotto (13 April 2006). "metalloid, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ↑ A. Marinov, A. Pape, D. Kolb, L. Halicz, I. Segal, N. Tepliakov and R. Brandt (2011). "Enrichment of the Superheavy Element Roentgenium (Rg) in Natural Au". International Journal of Modern Physics E 20 (11): 2391-2401. doi:10.1142/S0218301311020393. http://www.phys.huji.ac.il/~marinov/publications/Rg_261_arXiv_77.pdf. Retrieved 2014-04-08.

- ↑ Klaus Hinkelmann, Oscar Kempthorne (2008). Design and Analysis of Experiments, Volume I: Introduction to Experimental Design (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-72756-9. http://books.google.com/?id=T3wWj2kVYZgC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ R. A. Bailey (2008). Design of comparative experiments. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68357-9. http://www.cambridge.org/uk/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521683579.

- ↑ "Treatment and control groups, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. May 18, 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-31.

- ↑ "proof of concept, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. November 10, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ↑ Ginger Lehrman and Ian B Hogue, Sarah Palmer, Cheryl Jennings, Celsa A Spina, Ann Wiegand, Alan L Landay, Robert W Coombs, Douglas D Richman, John W Mellors, John M Coffin, Ronald J Bosch, David M Margolis (August 13, 2005). "Depletion of latent HIV-1 infection in vivo: a proof-of-concept study". Lancet 366 (9485): 549-55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67098-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1894952/. Retrieved 2012-05-09.

External links

![]() This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

| |

Educational level: this is a research resource. |

| |

Resource type: this resource is an article. |

| |

Resource type: this resource contains a lecture or lecture notes. |

| |

Subject classification: this is a Geology resource. |