Minerals/Metalloids

< Minerals

Metalloids are elements whose properties are intermediate between metals and solid nonmetals or semiconductors.

A variety of elements are often considered metalloids:

- boron, considered here in the boronides,

- aluminum, a face-centered cubic metal, considered in the aluminides,

- silicon, here in the siliconides,

- gallium (it can occur in the liquid state as a mineraloid),

- germanium,

- arsenic,

- selenium, also included in the chalcogens,

- indium,

- tin,

- antimony,

- tellurium, also included in the chalcogens,

- polonium, considered as among the heavy metals and

- astatine, here is with the halogens.

Minerals

Each of the metalloids, in the native or elemental form has at least one crystal structure, but these structures may not be the usual cubic structures: face-centered cubic or body-centered cubic that metals often occur in.

Galliums

While native gallium would be the best source of gallium, it apparently does not occur on Earth.

Gallite (CuGaS2) is 25 at % gallium.

Germaniums

The sample of germanite on the right has a composition of Cu26Fe4Ge4S32. Generally, germanite has a composition closer to Cu3(Ge, Ga, Fe, Zn) (S,As)4.[1] "This sample also contains tennantite."[2]

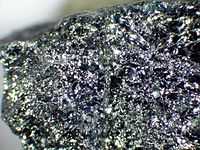

Arsenics

Native arsenic such as in the image on the right and at the top of this resource occurs in silver ore veins.

Allemontites

Allemontite is a native alloy of arsenic and antimony, with a composition of AsSb.[1]

The first example on the right is from the mineral collection of Brigham Young University Department of Geology, Provo, Utah.

The second is from Příbram, Central Bohemia Region, Bohemia (Böhmen; Boehmen), Czech Republic.

As a natural source of arsenic, it has 50 at % arsenic.

Seleniums

On the right is a photograph of native selenium from the mineral collection of Brigham Young University Department of Geology, Provo, Utah.

The second image down on the right shows dark gray selenium in sandstone from Westwater Canyon Section 23 Mine Grants, New Mexico.

Indiums

On the right are microprobe fragments of native indium from Eastern Transbaikal, Russia. The electron microprobe confirms that indium is the only component of the metallic phase.

Tins

Native tin such as in the images on the right occurs in two crystal forms: α-Sn (cubic) and β-Sn (tetragonal).[1]

Antimonies

Native antimony such as occurs in the rock on the upper right with its various oxidation products is crystalline in the hexagonal system.

The second image shows hexagonal crystals with metallic luster.

Telluriums

On the right is an example of native tellurium from the Emperor Mine, Vatukoula, Tavua Gold Field, Viti Levu, Fiji.

Research

Hypothesis:

- Traditional metalloid recovery processes applicable on Earth may not be so applicable on other astronomical objects such as Mars or the Moon.

Control groups

The findings demonstrate a statistically systematic change from the status quo or the control group.

“In the design of experiments, treatments [or special properties or characteristics] are applied to [or observed in] experimental units in the treatment group(s).[3] In comparative experiments, members of the complementary group, the control group, receive either no treatment or a standard treatment.[4]"[5]

Proof of concept

Def. a “short and/or incomplete realization of a certain method or idea to demonstrate its feasibility"[6] is called a proof of concept.

Def. evidence that demonstrates that a concept is possible is called proof of concept.

The proof-of-concept structure consists of

- background,

- procedures,

- findings, and

- interpretation.[7]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Willard Lincoln Roberts, George Robert Rapp, Jr., and Julius Weber (1974). Encyclopedia of Minerals. 450 West 33rd Street, New York, New York 10001 USA: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company. pp. 121-2. ISBN 0-442-26820-3.

- ↑ Klaus Hinkelmann, Oscar Kempthorne (2008). Design and Analysis of Experiments, Volume I: Introduction to Experimental Design (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-72756-9. http://books.google.com/?id=T3wWj2kVYZgC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ R. A. Bailey (2008). Design of comparative experiments. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68357-9. http://www.cambridge.org/uk/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521683579.

- ↑ "Treatment and control groups, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. May 18, 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-31.

- ↑ "proof of concept, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. November 10, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ↑ Ginger Lehrman and Ian B Hogue, Sarah Palmer, Cheryl Jennings, Celsa A Spina, Ann Wiegand, Alan L Landay, Robert W Coombs, Douglas D Richman, John W Mellors, John M Coffin, Ronald J Bosch, David M Margolis (August 13, 2005). "Depletion of latent HIV-1 infection in vivo: a proof-of-concept study". Lancet 366 (9485): 549-55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67098-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1894952/. Retrieved 2012-05-09.

External links

![]() This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

| |

Development status: this resource is experimental in nature. |

| |

Educational level: this is a research resource. |

| |

Resource type: this resource is an article. |

| |

Resource type: this resource contains a lecture or lecture notes. |

| |

Subject classification: this is a Geology resource. |