Minerals/Halogens

< Minerals

Halogens are elements in column 7A of the periodic table. They occur as a principal component in a variety of minerals.

On the right, is an example of almost completely clear fluorite (CaF2).

Impurities can give color. Some halogen minerals are called halides.

Fluorines

.png)

Although they do not occur naturally on the surface of the Earth, the phase diagram on the right shows temperatures and pressures for α-F (monoclinic) and β-F (cubic).

Fluorine-containing minerals are those that may provide a commercially viable source for the element either here on Earth or elsewhere.

Tysonite, or fluocerite, is a lanthanide fluoride, usually CeF3, for 75 atomic percent fluorine. It occurs in pegmatites on Earth.

In terms of atomic percent, fluorite (CaF2) is 66.7 % fluorine. It occurs on Earth usually as a hydrothermal deposit.

"Fluorite occurs in blue, purple, white, yellow, and colorless varieties. From field relationships the crystallization order was determined to have been blue and purple fluorite, which are commonly interlayered, followed by white, and finally yellow and colorless varieties."[1]

"Throughout most of the fluorite zone purple is the dominant, and commonly the only, color exhibited by fluorite, but in the central parts of the field green fluorite is quantitatively important, whereas at the edges of zone the fluorite is amber in color."[2]

Cryolite (Na3AlF6) is 60 % fluorine. It occurs on Earth primarily in pegmatites.

Chlorines

USGOV.jpg)

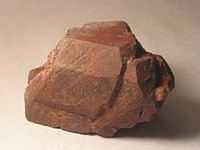

Halite is probably the most common mineral containing chlorine at 50 at %. It is a cubic mineral usually found in arid locations on Earth. Occurrences have clear, white, purple, blue, yellow, orange, and red varieties.

Bromines

Bromyrite, or bromargyrite, is a cubic silver bromide mineral (AgBr) that is 50 at % bromine.

Iodines

Iodyrite (AgI) may be the most common mineral with large amounts of iodine found on Earth. It is 50 at % iodine.

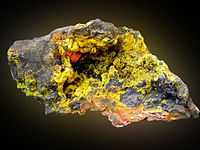

On the right are twinned iodyrite, or iodargyrite, crystals are within a rock sample from Schöne Aussicht Mine, Dernbach, Neuwied, Wied Iron Spar District, Westerwald, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Astatines

All of the known isotopes of astatine are very short-lived. It occurs naturally in minerals such as uraninite as a decay product of uranium.

Technology

"If you hold a prism up against sunlight, a rainbow spectrum will appear. This is due to the fact that different wavelengths of light refract – or bend – at different points within the prism. The same phenomenon occurs to a lesser degree in photographic lenses, where it is known as chromatic aberration. It's most noticeable in photographs as colour fringing at the edges of objects. Combining convex and concave lenses helps to correct the problem but does not entirely resolve it."[3]

"Fluorite, which boasts a very low dispersion of light, is capable of combatting the residual aberration that standard optical glass fails to eliminate. Canon succeeded in artificially creating crystal fluorite in the 1960s, producing the first interchangeable SLR lenses with fluorite elements. In the 1970s, Canon achieved the first UD (Ultra Low Dispersion) lens elements incorporating low-dispersion optical glass. This technology was further improved to create Super UD lenses in the 1990s. A combination of fluorite, UD and Super UD elements are used in many of today's super-telephoto L series lenses, telephoto zooms and wide-angle lenses."[3]

Research

Hypothesis:

- Although halogens form ionic bonds, natural compounds exist that allow halogen vapors.

Control groups

The findings demonstrate a statistically systematic change from the status quo or the control group.

“In the design of experiments, treatments [or special properties or characteristics] are applied to [or observed in] experimental units in the treatment group(s).[4] In comparative experiments, members of the complementary group, the control group, receive either no treatment or a standard treatment.[5]"[6]

Proof of concept

Def. a “short and/or incomplete realization of a certain method or idea to demonstrate its feasibility"[7] is called a proof of concept.

Def. evidence that demonstrates that a concept is possible is called proof of concept.

The proof-of-concept structure consists of

- background,

- procedures,

- findings, and

- interpretation.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ David A. S. Palmer and Anthony E. Williams-Jones (1 August 1996). "Genesis of the carbonatite-hosted fluorite deposit at Amba Dongar, India; evidence from fluid inclusions, stability isotopes, and whole rock-mineral geochemistry". Economic Geology 91 (5): 934-50. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.91.5.934. http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Anthony_Williams-Jones/publication/235451415_Genesis_of_the_carbonatite-hosted_fluorite_deposit_at_Amba_Dongar_India_evidence_from_fluid_inclusions_stability_isotopes_and_whole_rock-mineral_geochemistry/links/54ceb1170cf29ca810fcad30.pdf. Retrieved 2015-07-27.

- ↑ F. J. Sawkins (1 March 1966). "Ore genesis in the North Pennine orefield, in the light of fluid inclusion studies". Economic Geology 61 (2): 385-401. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.61.2.385. http://economicgeology.org/content/61/2/385.short. Retrieved 2015-07-27.

- 1 2 Canon (2015). "Canon Fluorite and UD Lenses". United Kingdom: Canon. Retrieved 2015-07-27.

- ↑ Klaus Hinkelmann, Oscar Kempthorne (2008). Design and Analysis of Experiments, Volume I: Introduction to Experimental Design (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-72756-9. http://books.google.com/?id=T3wWj2kVYZgC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ R. A. Bailey (2008). Design of comparative experiments. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68357-9. http://www.cambridge.org/uk/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521683579.

- ↑ "Treatment and control groups, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. May 18, 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-31.

- ↑ "proof of concept, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. November 10, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ↑ Ginger Lehrman and Ian B Hogue, Sarah Palmer, Cheryl Jennings, Celsa A Spina, Ann Wiegand, Alan L Landay, Robert W Coombs, Douglas D Richman, John W Mellors, John M Coffin, Ronald J Bosch, David M Margolis (August 13, 2005). "Depletion of latent HIV-1 infection in vivo: a proof-of-concept study". Lancet 366 (9485): 549-55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67098-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1894952/. Retrieved 2012-05-09.

External links

![]() This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

| |

Educational level: this is a research resource. |

| |

Resource type: this resource is an article. |

| |

Resource type: this resource contains a lecture or lecture notes. |

| |

Subject classification: this is a Geology resource. |