Introduction to finite elements/Choosing weight function

< Introduction to finite elementsChoice of Weighting Functions

As you have seen, we need to know the weighting functions (also called test functions) in order to define the weak (or variational) statement of the problem more precisely.

Consider the second model problem (3). If  is a weighting function, then the weak form of equation (3) is

is a weighting function, then the weak form of equation (3) is

Let the possible weighting functions  for this equation be such that they satisfy the boundary conditions, that is

for this equation be such that they satisfy the boundary conditions, that is  and

and  . This set of weighting functions will be denoted by the symbol

. This set of weighting functions will be denoted by the symbol  .

.

The exact weak form of the problem can then be stated as:

To get to an approximate weak form, we need to choose trial functions. Let these trial functions ( ) reside in the function space

) reside in the function space  . The approximate weak form of the problem is

. The approximate weak form of the problem is

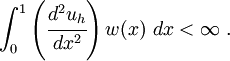

One requirement that these trial functions ( ) have to satisfy is that

) have to satisfy is that

The trial functions also have to satisfy the boundary conditions.

If you look at the weak form shown above, you will notice that the highest derivatives of  are of the second order while there are no derivatives of

are of the second order while there are no derivatives of  . This leads to a lack of symmetry in the formulation that is usually avoided for numerical reasons.

. This leads to a lack of symmetry in the formulation that is usually avoided for numerical reasons.

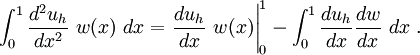

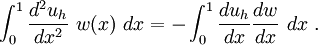

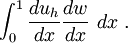

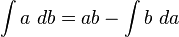

To get a symmetric weak form, we integrate the first term inside the integral by parts to get

(Recall that the formula for integration by parts is  .)

.)

Applying the boundary conditions on  , we get

, we get

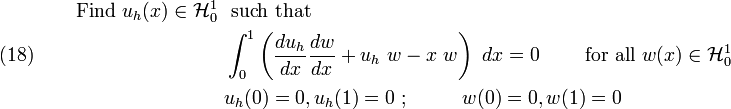

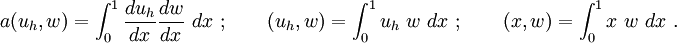

Therefore the problem can be restated in symmetric form as :

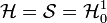

Since the same order of derivatives appear in both the trial and the weighting functions, we can choose our functions from the same set  , where

, where  . As you can see, the smoothness requirements on

. As you can see, the smoothness requirements on  are further weakened. This boundary value problem is also called the variational boundary value problem.

are further weakened. This boundary value problem is also called the variational boundary value problem.

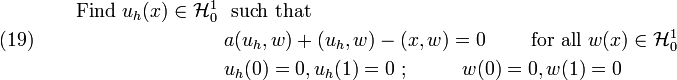

The variational boundary value problem (18) can be (and often is) written using bilinear function notation as

where

Characteristics of

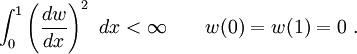

Let us now characterize  , the class of admissible functions for the problem. We know that if

, the class of admissible functions for the problem. We know that if  and

and  are irregular then their derivatives are even more irregular. Therefore, the most irregular term in the problem statement is

are irregular then their derivatives are even more irregular. Therefore, the most irregular term in the problem statement is

Now, both  and

and  are functions in the space

are functions in the space  . So we can choose

. So we can choose  to be equal to

to be equal to  . Hence the minimum requirement for

. Hence the minimum requirement for  is

is

Functions like the above are called square integrable.

Thus, our weighting functions have to be square integrable. This is a stricter condition than just requiring  to be piecewise continuous, and reduces the number of functions that you can choose from.

to be piecewise continuous, and reduces the number of functions that you can choose from.

There are two other interesting properties of the space  . These are :

. These are :

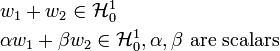

- It is a linear space which means that if

and

and  are two arbitrary functions in this space, then the following operations hold :

are two arbitrary functions in this space, then the following operations hold :

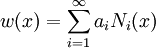

- It is an infinite dimensional space. This means that an infinity of parameters are needed to uniquely determine a weighting function

. Thus,

. Thus,

- where,

are linearly independent functions (also called basis functions) and

are linearly independent functions (also called basis functions) and  are constants. If we choose only

are constants. If we choose only  of these basis functions

of these basis functions  then this is a

then this is a  -dimensional (i.e., finite dimensional) subspace of

-dimensional (i.e., finite dimensional) subspace of  and we denote this as

and we denote this as  .

.

![\text{(17)} \qquad

{

\int^1_0 \left[-\frac{d^2}{dx^2}[u(x)] + u(x) - x\right]~w(x)~dx= 0

}](../I/m/0244358b711f3f725eedd1f20e169d81.png)

![\begin{align}

\text{Find}~ u(x)~& ~\text{such that} \\

& \int^1_0 \left[-\frac{d^2}{dx^2}[u(x)] + u(x) - x\right] w(x) ~dx

\qquad \text{for all} ~ w(x) \in \mathcal{H} \\

& u(0) = 0, u(1) = 0 ~;~~ \qquad w(0) = 0, w(1) = 0 ~.

\end{align}](../I/m/937f8bab85ca89f994a358cddcdc3f82.png)

![\begin{align}

\text{Find}~ u_h(x) \in \mathcal{S} ~& ~\text{such that} \\

& \int^1_0 \left[-\frac{d^2}{dx^2}[u_h(x)] + u_h(x) - x\right] w(x) ~dx

\qquad \text{for all} ~ w(x) \in \mathcal{H} \\

& u_h(0) = 0, u_h(1) = 0 ~;~~ \qquad w(0) = 0, w(1) = 0 ~.

\end{align}](../I/m/db8a244eeeae676594576da3d84a25cf.png)