Geophysics

Physics is involved in the geological processes that occur. When a laboratory experiment is performed to emulate a natural geological process that is geophysics. When a natural process is explained using physics as described in a laboratory that too is geophysics.

The image on the right presents the results of the GRACE mission as a gravity model of the Earth.

"The Grace mission uses twin satellites to make precise gravity-field measurements to study changes on Earth. Signal achievements include the first uniform measurement of Greenland and Antarctic ice mass changes and monthly estimates of water accumulation in the world's river basins."[1]

Theoretical geophysics

Def. "the physical processes and phenomena occurring in the earth and in its vicinity"[2] is called geophysics.

Once a phenomenon has been perceived or observed the next step is to suggest possible physical processes that may be occurring to produce the phenomenon.

Abrasion

Def. an "effect of mechanical erosion of rock, especially a river bed, by rock fragments scratching and scraping it"[3] is called abrasion.

The striations in the image on the right on Cerro Chirripo suggest a past glacier.

Def. "gouges [striations] cut into the bedrock by gravel and rocks carried by glacial ice and meltwater"[4] are called glacial striations.

"Parallel striations and bedrock fracture trends (across the left side of the image [on the left]) are clearly visible in this photo [at the right]."[4]

Def. "polished striated rock surfaces caused by one rock mass moving across another on a fault"[5] are called slickensides.

Avalanches

Def. a "large mass or body of snow and ice sliding swiftly down a mountain side, or falling down a precipice"[6] is called an avalanche.

Chatter marks

Def. "striations or marks left on the surface of exposed bedrock caused by the advance and retreat of glacier ice"[4] are called chattermarks.

In the image at the right is a close "up of chatter marks, Mt. Sirius, Antarctica. Lens cap in the photo is five centimeters across."[4]

Comminution

Def. a "breaking or grinding up of a material to form smaller particles"[7] is called comminution.

Entrainment

Def. any "of several processes in which a solid or liquid is put into motion by a fluid"[8] is called entrainment.

Flutes

Def. "a lengthwise groove"[9] is called a flute.

Grooves

Def. a "long, narrow channel or depression"[10] is called a groove.

Def. "grooves [...] cut into the bedrock by gravel and rocks carried by glacial ice and meltwater"[4] are called glacial grooves.

Plucking

Def. the "mechanical removal of pieces of rock from a bedrock face that is in contact with glacier ice"[11] is called plucking.

"Blocks are quarried and prepared for removal by the freezing and thawing of water in cracks, joints, and fractures. The resulting pieces are frozen into the glacier ice and transported."[11]

Rock slides

Def. a "falling of large amounts of rubble, earth and stones down the slope of a hill or mountain"[12] is called a rock slide.

Tribology

Def. a "force that resists the relative motion or tendency to such motion of two bodies in contact"[13] is called friction.

Def. "damage to the appearance and/or strength of an item caused by use over time"[14] is called wear.

Def. "application of a substance [...], between moving surfaces in contact in order to reduce friction and minimize heating"[15] is called lubrication.

Def. the "science and engineering of interacting surfaces in relative motion; the study and application of technology using the principles of friction, lubrication and wear"[16] is called tribology.

Polish

"Grooves are gouged into the tough rock [in the image on the right] by the continental glacier that once covered the area."[17]

"Ice won't scratch rock, of course; the sediment picked up by the glacier does the work. Stones and boulders in the ice leave scratches while sand and grit polish things smooth. The top of this outcrop looks wet, but instead it's glacial polish."[17]

Cryoseisms

Def. a "seismic event caused by sudden glacial movements or by a sudden cracking action in frozen soil or rock saturated with water or ice"[18] is called a cryoseism.

"A cryoseism, or frost quake, is a natural phenomenon that produces ground shaking and noises similar to an earthquake, but is caused by sudden deep freezing of the ground. They typically occur in the first cold snap of the year when temperatures drop from above freezing to below zero, particularly if there is no snow cover to insulate the ground. The primary way that they are recognized is that, in contrast to an earthquake, the effects of a cryoseism are very localized. In some cases, people in houses a few hundred yards away do not notice anything. The reason that the vibrations do not travel very far is that cryoseisms don't release much energy compared with a true earthquake caused by dislocation of rock within the earth. On the other hand, since cryoseisms occur at the ground surface they can cause significant effects right at the site, enough to jar people awake. Cryoseisms typically occur between midnight and dawn, during the coldest part of the night. If conditions are right, they may occur in a series of booms and shakes over a few hours or even on successive nights."[19]

"Cryoseisms have been reported from upstate New York, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Maine."[19]

Low-frequency "vibrations [from] over a hundred quakes have happened in the last decade that aren’t along any fault line. What are they near instead? Ice. A glacier can be thought of as a very slow-moving stream. It’s made of solid ice, but over long periods of time it can flow gradually over the land, sometimes carving deep trenches and bulldozing up rock and soil. Just because it takes centuries to rearrange things, though, doesn’t mean a glacier isn’t enormously powerful at any given moment."[20]

Numerous "low-frequency quakes in Greenland [have] been identified. [They] mostly occurred during July, August, and September. Those warmer months melt lots of glacial ice."[20]

In the warmer months, liquid "water is pooling underneath the glacial ice to the point where the thin veneer of water at the base of the glacier allows the whole mass to slip a little [...] The quakes [may be] the vibrations set up by all that ice–in one case, six cubic miles of it–skidding as much as forty-two feet in under a minute. When that much ice scrapes, the earth itself shakes."[20]

"The magnitude of these glacial quakes can be substantial. An ice slab roughly the size of Manhattan Island, and as tall as the Empire State building, slipping 10- meters (33 feet) causes a magnitude 5 quake."[21]

"Furthermore, the ice quake duration can last thousands of seconds whereas a normal earthquake might last hundreds of seconds."[21]

A "sharp increase [has occurred] in the number of quakes recorded in recent years. All 136 of the best-documented slips were traced to glaciated valleys draining the main Greenland ice sheet. A few others occurred in Alaskan glaciers or on Antarctica."[21]

These "glacial quakes ranged from six to 15 per year from 1993 to 2002, then jumped to 20 in 2003, 23 in 2004, and 32 in 2005. This rate increase matches an increase in Greenland's temperatures."[21]

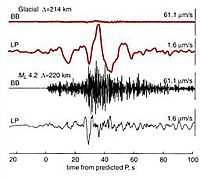

The image on the right shows seismographs "from the Dall Glacier area of Alaska. The upper two traces (in red) are the broad band (BB) and long-period (LP) records of the M 5.0 event of September 1999. The lower two traces (in black) are the BB and LP records of an M 4.2 earthquake in the same area."[21]

Surges

"The largest modern surges known to have occurred on the northern hemisphere are those of Brúarjökull. During the most recent surges in 1890 and 1964 an area of 1400 km2 of the glacier was affected and the glacier advanced 8-10 km onto the forefield (Thorarinsson 1969)."[22]

"When Brúarjökull surged, large ice-marginal moraines which can be traced over many kilometers, were produced in front of the glacier."[22]

"The lateral changes reflected in the spatial distribution of landform assemblages are closely linked to the dynamic behaviour of Brúarjökull. Therefore it is important to understand large-scale development in ice dynamics linked to the landscape evolution. Underlying this is the importance of understanding the factors controlling the surging behaviour of the glacier."[22]

Joints

Def. a "fracture in which the strata are not offset"[23] is called a joint.

Def. a "fracture in rock in which (unlike a fault) the strata do not move relative to each other"[24] is called a geologic joint.

Def. a "thin fracture, in sedimentary rocks, either normal or oblique to the bedding plane"[25] is called a leptoclase.

Research

Hypothesis:

- Once the charge on a proof mass matches the natural electric field of the Earth, an increase in negative charge should cause the proof mass to rise.

Control groups

The findings demonstrate a statistically systematic change from the status quo or the control group.

“In the design of experiments, treatments [or special properties or characteristics] are applied to [or observed in] experimental units in the treatment group(s).[26] In comparative experiments, members of the complementary group, the control group, receive either no treatment or a standard treatment.[27]"[28]

Proof of concept

Def. a “short and/or incomplete realization of a certain method or idea to demonstrate its feasibility"[29] is called a proof of concept.

Def. evidence that demonstrates that a concept is possible is called proof of concept.

The proof-of-concept structure consists of

- background,

- procedures,

- findings, and

- interpretation.[30]

See also

References

- ↑ Alan Buis and Tabatha Thompson (11 December 2007). "Amazing Grace Team Receives Prestigious Award". Pasadena, California USA: MASA-JPL. Retrieved 2015-10-21.

- ↑ "geophysics, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 28 August 2014. Retrieved 2014-11-23.

- ↑ "abrasion, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 7 November 2014. Retrieved 2014-11-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jane Beitler (19 September 2014). "Cryosphere Glossary". National Snow and Ice Data Center. Retrieved 2014-09-17.

- ↑ David Laurent (July 24, 2012). "Earthquake Glossary - slickensides". Menlo Park, California USA: USGS. Retrieved 2014-12-04.

- ↑ "avalanche, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 25 September 2014. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- ↑ "comminution, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 18 June 2013. Retrieved 2014-11-23.

- ↑ "entrainment, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 7 November 2013. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- ↑ "flute, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 22 August 2014. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- ↑ "groove, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 9 October 2014. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- 1 2 Eleyne Phillips (16 December 2004). "Glossary of Glacier Terminology". Reston, Virginia USA: United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2014-11-09.

- ↑ "slide, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 9 November 2014. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- ↑ "friction, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 20 November 2014. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- ↑ "wear, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 20 November 2014. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- ↑ "lubrication, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 28 May 2014. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- ↑ "tribology, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 23 May 2014. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- 1 2 Hunter (November 2014). "Glacial Grooves & Polish: Central Park, NY". New York, NY USA: CUNY. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- ↑ "cryoseism, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 6 February 2014. Retrieved 2014-11-25.

- 1 2 Andrew V. Lacroix (6 October 2005). "Cryoseisms (or frost quakes) in Maine". Maine Geological Survey. Retrieved 2014-11-25.

- 1 2 3 Göran Ekström (9 September 2004). "Ice Quake!". Moments of Science. Retrieved 2014-11-25.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tom Irvine (June 2006). "Ice Quakes". VibrationData.com. Retrieved 2014-11-26.

- 1 2 3 Kurt Kjær and Ólafur Ingólfsson (2005). "The Brúarjökull Project: Sedimentary environments of a surging glacier". Iceland: The Brúarjökull Project. Retrieved 2014-11-27.

- ↑ "joint, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 4 January 2015. Retrieved 2015-02-16.

- ↑ "geologic joint, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 20 June 2013. Retrieved 2015-02-16.

- ↑ "title, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 17 October 2013. Retrieved 2015-02-19.

- ↑ Klaus Hinkelmann, Oscar Kempthorne (2008). Design and Analysis of Experiments, Volume I: Introduction to Experimental Design (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-72756-9. http://books.google.com/?id=T3wWj2kVYZgC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ R. A. Bailey (2008). Design of comparative experiments. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68357-9. http://www.cambridge.org/uk/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521683579.

- ↑ "Treatment and control groups, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. May 18, 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-31.

- ↑ "proof of concept, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. November 10, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ↑ Ginger Lehrman and Ian B Hogue, Sarah Palmer, Cheryl Jennings, Celsa A Spina, Ann Wiegand, Alan L Landay, Robert W Coombs, Douglas D Richman, John W Mellors, John M Coffin, Ronald J Bosch, David M Margolis (August 13, 2005). "Depletion of latent HIV-1 infection in vivo: a proof-of-concept study". Lancet 366 (9485): 549-55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67098-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1894952/. Retrieved 2012-05-09.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![]() This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org