Continuum mechanics/Thermodynamics of continua

< Continuum mechanicsGoverning Equations

The equations that govern the thermomechanics of a solid include the balance laws for mass, momentum, and energy. Kinematic equations and constitutive relations are needed to complete the system of equations. Physical restrictions on the form of the constitutive relations are imposed by an entropy inequality that expresses the second law of thermodynamics in mathematical form.

The balance laws express the idea that the rate of change of a quantity (mass, momentum, energy) in a volume must arise from three causes:

- the physical quantity itself flows through the surface that bounds the volume,

- there is a source of the physical quantity on the surface of the volume, or/and,

- there is a source of the physical quantity inside the volume.

Let  be the body (an open subset of Euclidean space) and let

be the body (an open subset of Euclidean space) and let  be its surface (the boundary of

be its surface (the boundary of  ).

).

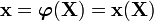

Let the motion of material points in the body be described by the map

where  is the position of a point in the initial configuration and

is the position of a point in the initial configuration and  is the location of the same point in the deformed configuration.

is the location of the same point in the deformed configuration.

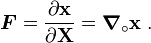

Recall that the deformation gradient ( ) is given by

) is given by

Balance Laws

Let  be a physical quantity that is flowing through the body. Let

be a physical quantity that is flowing through the body. Let  be sources on the surface of the body and let

be sources on the surface of the body and let  be sources inside the body. Let

be sources inside the body. Let  be the outward unit normal to the surface

be the outward unit normal to the surface  . Let

. Let  be the velocity of the physical particles that carry the physical quantity that is flowing. Also, let the speed at which the bounding surface

be the velocity of the physical particles that carry the physical quantity that is flowing. Also, let the speed at which the bounding surface  is moving be

is moving be  (in the direction

(in the direction  ).

).

Then, balance laws can be expressed in the general form

Note that the functions  ,

,  , and

, and  can be scalar valued, vector valued, or tensor valued - depending on the physical quantity that the balance equation deals with.

can be scalar valued, vector valued, or tensor valued - depending on the physical quantity that the balance equation deals with.

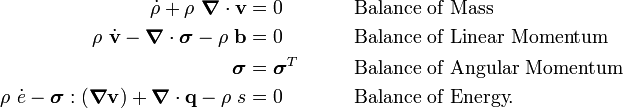

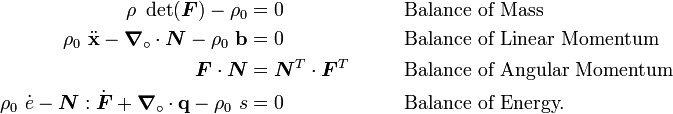

It can be shown that the balance laws of mass, momentum, and energy can be written as

|

|

In the above equations  is the mass density (current),

is the mass density (current),  is the material time derivative of

is the material time derivative of  ,

,  is the particle velocity,

is the particle velocity,  is the material time derivative of

is the material time derivative of  ,

,  is the Cauchy stress tensor,

is the Cauchy stress tensor,  is the body force density,

is the body force density,  is the internal energy per unit mass,

is the internal energy per unit mass,  is the material time derivative of

is the material time derivative of  ,

,  is the heat flux vector, and

is the heat flux vector, and  is an energy source per unit mass.

is an energy source per unit mass.

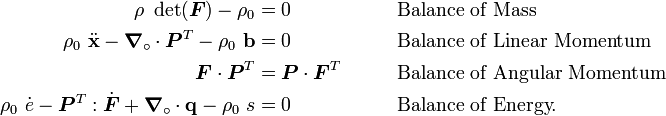

With respect to the reference configuration, the balance laws can be written as

|

|

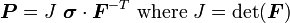

In the above,  is the first Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor, and

is the first Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor, and  is the mass density in the reference configuration. The first Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor is related to the Cauchy stress tensor by

is the mass density in the reference configuration. The first Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor is related to the Cauchy stress tensor by

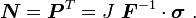

We can alternatively define the nominal stress tensor  which is the transpose of the first Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor such that

which is the transpose of the first Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor such that

Then the balance laws become

Keep in mind that:

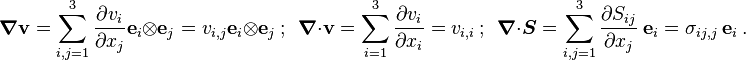

The gradient and divergence operators are defined such that

where

is a vector field,

is a second-order tensor field, and

are the components of an orthonormal basis in the current configuration. Also,

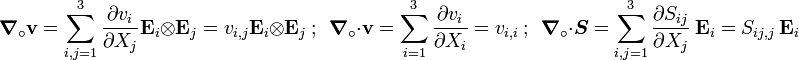

where

is a vector field,

is a second-order tensor field, and

are the components of an orthonormal basis in the reference configuration.

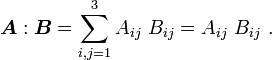

The inner product is defined as

The Clausius-Duhem Inequality

The Clausius-Duhem inequality can be used to express the second law of thermodynamics for elastic-plastic materials. This inequality is a statement concerning the irreversibility of natural processes, especially when energy dissipation is involved.

Just like in the balance laws in the previous section, we assume that there is a flux of a quantity, a source of the quantity, and an internal density of the quantity per unit mass. The quantity of interest in this case is the entropy. Thus, we assume that there is an entropy flux, an entropy source, and an internal entropy density per unit mass ( ) in the region of interest.

) in the region of interest.

Let  be such a region and let

be such a region and let  be its boundary. Then the second law of thermodynamics states that the rate of increase of

be its boundary. Then the second law of thermodynamics states that the rate of increase of  in this region is greater than or equal to the sum of that supplied to

in this region is greater than or equal to the sum of that supplied to  (as a flux or from internal sources) and the change of the internal entropy density due to material flowing in and out of the region.

(as a flux or from internal sources) and the change of the internal entropy density due to material flowing in and out of the region.

Let  move with a velocity

move with a velocity  and let particles inside

and let particles inside  have velocities

have velocities  . Let

. Let  be the unit outward normal to the surface

be the unit outward normal to the surface  . Let

. Let  be the density of matter in the region,

be the density of matter in the region,  be the entropy flux at the surface, and

be the entropy flux at the surface, and  be the entropy source per unit mass.

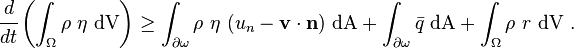

Then the entropy inequality may be written as

be the entropy source per unit mass.

Then the entropy inequality may be written as

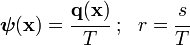

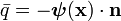

The scalar entropy flux can be related to the vector flux at the surface by the relation  . Under the assumption of incrementally isothermal conditions, we have

. Under the assumption of incrementally isothermal conditions, we have

where  is the heat flux vector,

is the heat flux vector,  is a energy source per unit mass, and

is a energy source per unit mass, and  is the absolute temperature of a material point at

is the absolute temperature of a material point at  at time

at time  .

.

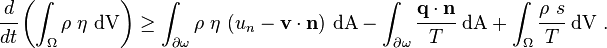

We then have the Clausius-Duhem inequality in integral form:

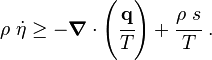

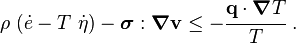

We can show that the entropy inequality may be written in differential form as

In terms of the Cauchy stress and the internal energy, the Clausius-Duhem inequality may be written as

|

Clausius-Duhem inequality |

References

- T. W. Wright. (2002) The Physics and Mathematics of Adiabatic Shear Bands. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- R. C. Batra. (2006) Elements of Continuum Mechanics. AIAA, Reston, VA.

- G. A. Maugin. (1999) The Thermomechanics of Nonlinear Irreversible Behaviors: An Introduction. World Scientific, Singapore.

- M. E. Gurtin. (1981) An Introduction to Continuum Mechanics. Academic Press, New York.

![\cfrac{d}{dt}\left[\int_{\Omega} f(\mathbf{x},t)~\text{dV}\right] =

\int_{\partial \Omega } f(\mathbf{x},t)[u_n(\mathbf{x},t) - \mathbf{v}(\mathbf{x},t)\cdot\mathbf{n}(\mathbf{x},t)]~\text{dA} +

\int_{\partial \Omega } g(\mathbf{x},t)~\text{dA} + \int_{\Omega} h(\mathbf{x},t)~\text{dV} ~.](../I/m/7c78cd1a16f3ada0af81945e9ea7ac84.png)