Charges/Interactions

< ChargesThe interactions of charges is fundamental to subluminal physics. The transformation of an electron to a photon and back is the key to electromagnetic propagation.

As a subluminal entity, the electron possesses mass and a spin (a spinon).

Charges

Charge is usually thought of as a property of matter that is responsible for electrical phenomena, existing in a positive or negative form.

Def. "the quantity of unbalanced positive or negative ions in or on an object; measured in coulombs"[1] is called charge, or electric charge.

Def. "a quasiparticle produced as a result of electron spin-charge separation"[2] is called a chargon.

A chargon possesses the charge of an electron without a spin.

A spinon, in turn, possesses the spin of an electron without charge. The suggestion is that an elementary particle such as a positron may consist of at least two parts: spin and charge.

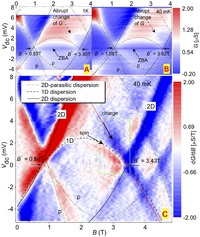

In the figure at the top of this section "the 1D parabola tracks the spin excitation (spinon)."[3]

Def. a "quasiparticle, corresponding to the orbital energy of an electron, which can result from an electron apparently ‘splitting’ under certain conditions"[4] is called an orbiton.

Both an orbiton and a spinon are kinetic or kinematic concepts applied to an electron.

Def. "a discrete particle having zero rest mass, no electric charge, and an indefinitely long lifetime"[5] is called a photon.

An electron may be thought of as a stable subatomic particle with a charge of negative one.

Interactions

"Laser pulses have been made to accelerate themselves around loops of optical fibre - which seems to go against Newton’s 3rd law. This states that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction."[6]

"Under Newton’s third law of motion, if we imagine one billiard ball striking another upon a pool table, the two balls will bounce away from each other. If one of the billiard balls had a negative mass, then the collision of the two balls would result in them accelerating in the same direction."[6]

Strong interactions

"The strong interaction is observable in two areas: on a larger scale (about 1 to 3 femtometers (fm)), it is the force that binds protons and neutrons (nucleons) together to form the nucleus of an atom. On the smaller scale (less than about 0.8 fm, the radius of a nucleon), it is also the force ... that [forms and holds together] protons, neutrons and other hadron particles."[7]

"In the context of binding protons and neutrons together to form atoms, the strong interaction is called the nuclear force (or residual strong force). [T]he strong interaction ... obeys a quite different distance-dependent behavior between nucleons ... ."[7]

"Another possibility [regarding neutron stars, called "baryon matter",] is that in the absence of gravity high-density baryonic matter is bound by purely strong forces. [...] nongravitationally bound bulk hadronic matter is consistent with nuclear physics data [...] and low-energy strong interaction data [...] The effective field theory approach has many successes in nuclear physics [...] suggesting that bulk hadronic matter is just as likely to be a correct description of matter at high densities as conventional, unbound hadronic matter."[8]

"The idea behind baryon matter is that a macroscopic state may exist in which a smaller effective baryon mass inside some region makes the state energetically favored over free particles. [...] This state will appear in the limit of large baryon number as an electrically neutral coherent bound state of neutrons, protons, and electrons in β-decay equilibrium."[8]

Electromagnetic interactions

"The [e]lectromagnetic interaction is a fundamental force of nature [that] is felt by charged [particles]. Its exchange particle is the photon (symbol γ) and the many forms of electromagnetic radiation are a manifestation of this interaction."[9]

"Sources of electromagnetic fields consist of two types of charge – positive and negative."[10]

The relative strengths and ranges of the charge interactions:

| Interaction | Mediator | Relative Magnitude | Behavior | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong interaction | gluon | 1038 | 1 | 10−15 m |

| Electromagnetic interaction | photon | 1036 | 1/r2 | universal |

| Weak interaction | W and Z bosons | 1025 | 1/r5 to 1/r7 | 10−16 m |

| Gravity interaction | photon | 10 | 1/r2 | universal |

From an electromagnetic-type interaction point of view, the gravity interaction, or gravitational interaction, is a heavily charge-balanced ever so slight excess of positive charge amounting to 10-36 of a proton for the mass of a proton. Gravity owes its ability to attract other objects due to their apparent charge excess often represented by mass.

Weak interactions

The weak interaction is expressed with respect to nuclear electrons and the continuous β-ray emission spectrum of β decay.[11]

Research

Hypothesis:

- The interactions of charges is the result of entanglements.

Control groups

The findings demonstrate a statistically systematic change from the status quo or the control group.

“In the design of experiments, treatments [or special properties or characteristics] are applied to [or observed in] experimental units in the treatment group(s).[12] In comparative experiments, members of the complementary group, the control group, receive either no treatment or a standard treatment.[13]"[14]

Proof of concept

Def. a “short and/or incomplete realization of a certain method or idea to demonstrate its feasibility"[15] is called a proof of concept.

Def. evidence that demonstrates that a concept is possible is called proof of concept.

The proof-of-concept structure consists of

- background,

- procedures,

- findings, and

- interpretation.[16]

See also

- Charge ontology

- Charges

- Circuit astronomy

- Effective masses

- Electrons

- Charges/Interactions/Electromagnetics

- Electrostatics

- Dynamos

- Magnetostatics

- Charges/Interactions/Strong

- Charges/Interactions/Weak

- Quanta

- Electromagnetic interaction

- Electrostatic suspension

- Electroweak interaction

- Energy phantoms/Lecture

- Intergalactic medium

- Interplanetary medium

- Interstellar medium

- Magnetic field reversal

- Plasmas/Magnetohydrodynamics

- Stars/Radiative dynamo

References

- ↑ "electric charge, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 24 July 2015. Retrieved 2015-08-08.

- ↑ Xhienne (30 April 2012). "chargon, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-08-08.

- ↑ Y. Jompol, C. J. B. Ford, J. P. Griffiths, I. Farrer, G. A. C. Jones, D. Anderson, D. A. Ritchie, T. W. Silk and A. J. Schofield (July 2009). "Probing spin-charge separation in a Tomonaga-Luttinger liquid". Science 325 (5940): 597-601. doi:10.1126/science.1171769. http://arxiv.org/pdf/1002.2782v1.pdf. Retrieved 2015-08-08.

- ↑ Widsith (19 April 2012). "orbiton, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-08-08.

- ↑ Poccil (18 October 2004). "photon, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-08-08.

- 1 2 GrrlScientist (22 October 2013). "Scientists have made light appear to break Newton’s third law". IFLScience. Retrieved 2015-09-28.

- 1 2 "Strong interaction, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. May 27, 2012. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- 1 2 Safi Bahcall, Bryan W. Lynn, and Stephen B. Selipsky (October 10, 1990). "New Models for Neutron Stars". The Astrophysical Journal 362 (10): 251-5. doi:10.1086/169261. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1990ApJ...362..251B. Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- ↑ "Electromagnetic interaction, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. March 17, 2006. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- ↑ "Electromagnetic field, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. July 1, 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-12.

- ↑ Fred L. Wilson (December 1968). "Fermi's Theory of Beta Decay". American Journal of Physics 36 (12): 1150-60. http://microboone-docdb.fnal.gov/cgi-bin/RetrieveFile?docid=953;filename=FermiBetaDecay1934.pdf;version=1. Retrieved 2012-06-24.

- ↑ Klaus Hinkelmann, Oscar Kempthorne (2008). Design and Analysis of Experiments, Volume I: Introduction to Experimental Design (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-72756-9. http://books.google.com/?id=T3wWj2kVYZgC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ R. A. Bailey (2008). Design of comparative experiments. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68357-9. http://www.cambridge.org/uk/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521683579.

- ↑ "Treatment and control groups, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. May 18, 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-31.

- ↑ "proof of concept, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. November 10, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ↑ Ginger Lehrman and Ian B Hogue, Sarah Palmer, Cheryl Jennings, Celsa A Spina, Ann Wiegand, Alan L Landay, Robert W Coombs, Douglas D Richman, John W Mellors, John M Coffin, Ronald J Bosch, David M Margolis (August 13, 2005). "Depletion of latent HIV-1 infection in vivo: a proof-of-concept study". Lancet 366 (9485): 549-55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67098-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1894952/. Retrieved 2012-05-09.

External links

![]() This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

| |

Development status: this resource is experimental in nature. |

| |

Educational level: this is a research resource. |

| |

Resource type: this resource is an article. |

| |

Resource type: this resource contains a lecture or lecture notes. |

| |

Subject classification: this is an astrophysics resource. |