Angular momentum and energy

Angular momentum and energy are concepts developed to try to understand everyday reality.

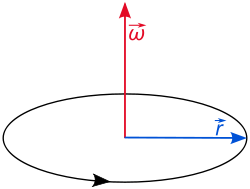

An angular momentum L of a particle about an origin is given by

where r is the radius vector of the particle relative to the origin, p is the linear momentum of the particle, and × denotes the cross product (r · p sin θ). Theta is the angle between r and p.

Evaluation

|

Fundamentals

Def. a "quantity [...] cohering together so as to make one body, or an aggregation of particles or things which collectively make one body or quantity"[1] is called a mass.

Mass is an idea.

Def. a "property of a body that resists any change to its uniform motion"[2] is called inertia.

Mass and inertia are generally considered equivalent.

Isaac Newton's laws of motion contain the idea of inertia.

Newton's First law: "Every body persists in its state of being at rest or of moving uniformly straight forward, except insofar as it is compelled to change its state by force impressed."[3]

While motion in a straight line, or rectilinear motion can be produced over limited distances in a laboratory, it may not occur naturally.

Def. "the product of [a body's] mass and velocity"[4] is called momentum.

Def. "the rotary inertia of a system [such as] an isolated rigid body [...] is a measure of the extent to which an object will continue to rotate in the absence of an applied torque"[5] is called angular momentum.

Def. a "rotational or twisting effect of a force"[6] is called a torque.

Def. a "turning effect of a force applied to a rotational system at a distance from the axis of rotation"[7] is called a moment of force.

"The moment is equal to the magnitude of the force multiplied by the perpendicular distance between its line of action and the axis of rotation."[7]

A torque and a moment of force are the same. Each is a "unit of work done, or energy expended".[8]

"For an object with a fixed mass that is rotating about a fixed symmetry axis, the angular momentum is expressed as the product of the moment of inertia of the object and its angular velocity vector:

where I is the moment of inertia of the object (in general, a tensor quantity), and ω is the angular velocity."[9]

The moment "of inertia is the mass property of a rigid body that defines the torque needed for a desired angular acceleration about an axis of rotation. Moment of inertia depends on the shape of the body and may be different around different axes of rotation. A larger moment of inertia around a given axis requires more torque to increase the rotation, or to stop the rotation, of a body about that axis. Moment of inertia depends on the amount and distribution of its mass, and can be found through the sum of moments of inertia of the masses making up the whole object, under the same conditions."[10]

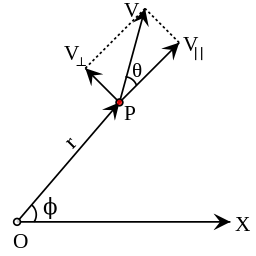

"In two dimensions the angular velocity ω is given by"[11]

"This is related to the cross-radial (tangential) velocity by:[12]"[11]

"An explicit formula for v⊥ in terms of v and θ is:"[11]

"Combining the above equations gives a formula for ω:"[11]

Problem 1

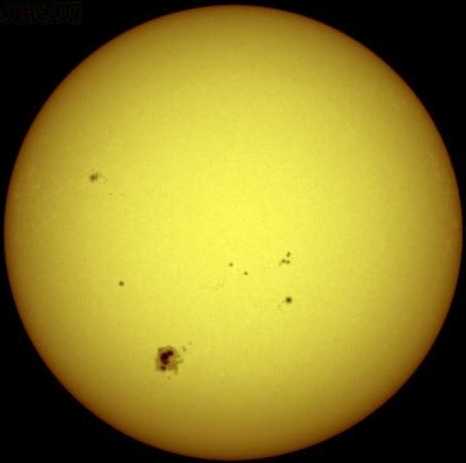

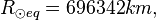

Using the following values, and considering the Sun to be a rigid, solid object, answer the questions below.

and

and

What is the angular velocity of the Sun?

What is its moment of inertia?

What is the Sun's angular momentum?

Estimate how much torque is necessary to bring the Sun's rotational velocity down to zero?

What are the units of angular momentum for the Sun?

Problem 2

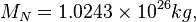

Using the following values, and considering Jupiter to be a rigid, solid object, answer the questions below.

and

and

What is the angular velocity of the Jupiter?

What is its moment of inertia?

What is the Jupiter's angular momentum from rotation?

Estimate how much torque is necessary to bring the Jupiter's rotational velocity down to zero?

Using a mean orbital radius between 8.16 x 108 km and 7.41 x 108 km, what's its angular momentum from revolution around the Sun?

Is the total angular momentum of Jupiter greater than the Sun's?

Problem 3

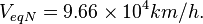

Using the following values, and considering Saturn to be a rigid, solid object, answer the questions below.

and

and

What is the angular velocity of the Saturn?

What is its moment of inertia?

What is the Saturn's angular momentum from rotation?

Estimate how much torque is necessary to bring the Saturn's rotational velocity down to zero?

Using a mean orbital radius between 1.51 x 109 km and 1.35 x 109 km, what's its angular momentum from revolution around the Sun?

Is the total angular momentum of Saturn greater than the Sun's?

Problem 4

Using the following values, and considering Uranus to be a rigid, solid object, answer the questions below.

and

and

What is the angular velocity of the Uranus?

What is its moment of inertia?

What is the Uranus's angular momentum from rotation?

Estimate how much torque is necessary to bring the Uranus's rotational velocity down to zero?

Using a mean orbital radius between 3.00 x 109 km and 2.75 x 109 km, what's its angular momentum from revolution around the Sun?

Is the total angular momentum of Uranus greater than the Sun's?

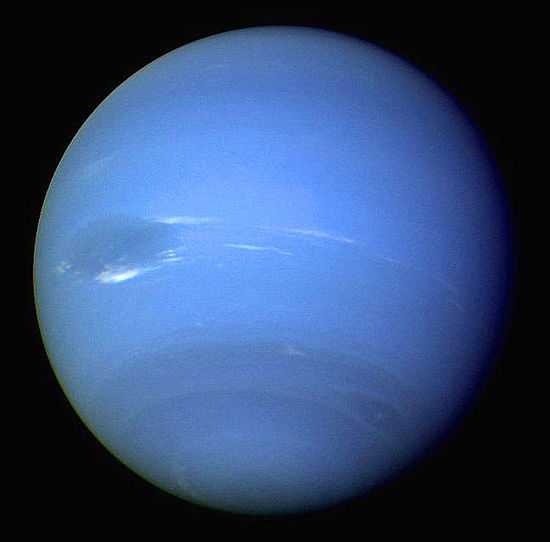

Problem 5

Using the following values, and considering Neptune to be a rigid, solid object, answer the questions below.

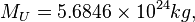

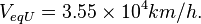

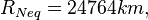

and

and

What is the angular velocity of the Neptune?

What is its moment of inertia?

What is the Neptune's angular momentum from rotation?

Estimate how much torque is necessary to bring the Neptune's rotational velocity down to zero?

Using a mean orbital radius between 4.55 x 1010 km and 4.45 x 1010 km, what's its angular momentum from revolution around the Sun?

Is the total angular momentum of Neptune greater than the Sun's?

Research

Hypothesis:

- To use angular momentum or energy a mass must be assigned.

Control groups

The findings demonstrate a statistically systematic change from the status quo or the control group.

“In the design of experiments, treatments [or special properties or characteristics] are applied to [or observed in] experimental units in the treatment group(s).[13] In comparative experiments, members of the complementary group, the control group, receive either no treatment or a standard treatment.[14]"[15]

Proof of concept

Def. a “short and/or incomplete realization of a certain method or idea to demonstrate its feasibility"[16] is called a proof of concept.

Def. evidence that demonstrates that a concept is possible is called proof of concept.

The proof-of-concept structure consists of

- background,

- procedures,

- findings, and

- interpretation.[17]

See also

References

- ↑ "mass, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. February 20, 2014. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ "inertia, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. February 20, 2014. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ Isaac Newton, The Principia, A new translation by I.B. Cohen and A. Whitman, University of California press, Berkeley 1999.

- ↑ "momentum, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. January 30, 2014. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ "angular momentum, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. October 9, 2013. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ "torque, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. January 10, 2014. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- 1 2 "moment of force, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. December 10, 2013. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ "foot-pound, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. June 20, 2013. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ "Angular momentum, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. February 27, 2014. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ "Moment of inertia, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. February 27, 2014. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- 1 2 3 4 "Angular velocity title, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. February 19, 2014. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ Russell C. Hibbeler (2009). Engineering Mechanics. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 314, 153. ISBN 978-0-13-607791-6. http://books.google.com/?id=tOFRjXB-XvMC&pg=PA314.

- ↑ Klaus Hinkelmann, Oscar Kempthorne (2008). Design and Analysis of Experiments, Volume I: Introduction to Experimental Design (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-72756-9. http://books.google.com/?id=T3wWj2kVYZgC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ R. A. Bailey (2008). Design of comparative experiments. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68357-9. http://www.cambridge.org/uk/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521683579.

- ↑ "Treatment and control groups, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. May 18, 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-31.

- ↑ "proof of concept, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. November 10, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ↑ Ginger Lehrman and Ian B Hogue, Sarah Palmer, Cheryl Jennings, Celsa A Spina, Ann Wiegand, Alan L Landay, Robert W Coombs, Douglas D Richman, John W Mellors, John M Coffin, Ronald J Bosch, David M Margolis (August 13, 2005). "Depletion of latent HIV-1 infection in vivo: a proof-of-concept study". Lancet 366 (9485): 549-55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67098-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1894952/. Retrieved 2012-05-09.

External links

- African Journals Online

- Bing Advanced search

- Google Books

- Google scholar Advanced Scholar Search

- International Astronomical Union

- JSTOR

- Lycos search

- NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database - NED

- NASA's National Space Science Data Center

- NCBI All Databases Search

- Office of Scientific & Technical Information

- Questia - The Online Library of Books and Journals

- SAGE journals online

- The SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System

- Scirus for scientific information only advanced search

- SDSS Quick Look tool: SkyServer

- SIMBAD Astronomical Database

- SIMBAD Web interface, Harvard alternate

- Spacecraft Query at NASA.

- SpringerLink

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Universal coordinate converter

- Wiley Online Library Advanced Search

- Yahoo Advanced Web Search

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![]() This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

| |

Educational level: this is a research resource. |

| |

Subject classification: this is an astronomy resource. |