Abstract concept generator

"They talk about an "abstract concept generator" [a generator or generative] which produces “some kind of abstract object” [that] represents the maximal content of a whole set of discourse deriving from this concept."[1]

Abstraction

Def.

- the "act of focusing on one characteristic of an object rather than the object as a whole group of characteristics; the act of separating said qualities from the object or ideas",[2]

- the "act of focusing on one characteristic of an object rather than the object as a whole group of characteristics; the act of separating said qualities from the object or ideas",[2] or

- the "act of comparing commonality between distinct objects and organizing using those similarities; the act of generalizing characteristics; the product of said generalization"[2]

is called abstraction.

Earth

On Earth past and present have been and are a number of species whose brain or central nervous system size, mass, or neuronal complexity at least in adults is necessary and sufficient to allow most individuals to think and conceive in the abstract. This allows them to make or utilize tools where possible or exhibit certain intuitive skills which are ear marks of the possession of an abstract concept generator.

Sperm whales

The image at the right is an aerial view of an adult sperm whale Physeter macrocephalus. "Sperm whales have the largest brain of any animal (on average 17 pounds (7.8 kg) in mature males)".[3] These sentient whales have the largest brains that have ever existed on Earth.

"Absolute size is the most general of all brain properties [...], and ranges in mammals from brains of small bats and insectivores (weighing less than 0.1 g) to those of large cetaceans (up to 9000 g)."[4]

Blue whales

The brain mass of one blue whale adult is 5,678 gms.[5] Although another adult was measured as about 6800 gms.[6]

Killer whales

Orcinus orca

The mean brain mass of Orcinus orca for six adults is 6,368 gms.[5]

Elephants

The average brain size of an adult African elephant, Loxodonta africana, imaged at the right, is around 4,200 gm.[4]

At the left is the genetically confirmed separate species, the African forest elephant, Loxodonta cyclotis. Its brain size or weight may not as yet been estimated from living adults.

The third living elephant shown at the lower right is the Indian elephant, Elephas maximus. The image is of an adult male. Its brain weight is comparable to the African elephant.

The imperial mammoth, Mammuthus imperaotor, shown at the second left lived in North America about 20,000 b2k.

The "mammoths and mastodons of present-day southwestern Ohio and northwestern Kentucky were homebodies that tended to stay in one area [...] The enamel on the animals' molars gave researchers clues as to where the mammoths and mastodons lived throughout their lives and what they ate. They discovered that mammoths ate grasses and sedges, whereas mastodons preferred leaves from trees or shrubs. Mammoths favored areas near retreating ice sheets, where grasses were plentiful, and mastodons fed near forested spaces."[7]

"I suspect that this was a pretty nice place to live, relatively speaking. [These] animals probably had what they needed to survive here year-round."[8]

"A group of scientists from the United States, Sweden, Canada, and the UK, has sequenced and analyzed the complete high-quality genomes of two woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) – one from northeastern Siberia and the other from Wrangel Island, located in the Arctic Ocean."[9]

The "genomes from specimens [were] taken from the remains of two male woolly mammoths, which lived about 40,000 years apart. One had lived in Siberia and is estimated to be 44,800 years old. The other – believed to be from one of the last surviving mammoth populations – lived roughly 4,300 years ago on Wrangel Island."[9]

“We found that the genome from one of the world’s last mammoths displayed low genetic variation and a signature consistent with inbreeding, likely due to the small number of mammoths that managed to survive on Wrangel Island during the last 5,000 years of the species’ existence.”[10]

“With a complete genome and this kind of data, we can now begin to understand what made a mammoth a mammoth – when compared to an elephant – and some of the underlying causes of their extinction which is an exceptionally difficult and complex puzzle to solve.”[11]

"Through careful analysis, the researchers determined the mammoth populations had suffered and recovered from a significant setback 250,000-300,000 years ago. However, another severe decline occurred in the final days of the Ice Age, marking the end."[9]

“The dates on these current samples suggest that when Egyptians were building pyramids, there were still mammoths living on these islands.”[11]

Dolphins

Like humans and dogs the brain of the toothed whales sits behind the eyes. The melon often seen on the front of the head of Tursiops truncatus (the common bottlenose dolphin) is not where its brain is located. The melon is used in echo-location.

Bottlenose dolphins

"Dolphins evolved from relatively small-brained animals like cows and hippos into this large-brained, highly specialized aquatic organism, [...] This is one of the first comprehensive studies to look at rates of molecular evolution in dolphins."[12]

"Because dolphins have also evolved large brains, it gives us an example of the independent evolution of big, complex brains to compare to the evolution of the human brain [...] By doing this, you can find out what is necessary for a big brain."[12]

Both humans and dolphins have mutations in the microcephalin gene.[13]

At the top of this resource is an image of Tursiops truncatus, the bottle-nosed dolphin, which in an average adult has a brain weight of about 2200 gms. One Tursiops truncatus adult female had a brain weight of 1,609 gm.[5] Several males averaged 1638 gms, but the ranges are 1,112-1,609 gms (females) and 954-1,910 gms (males) with an overall species average of 1,489 gms.[5]

Grand dolphins

The image at the right is of a grand dolphin, Tursiops aduncus, of the Indian Ocean. Here it is photographed in the Port River, Adelaide, Australia.

The brain size of this dolphin may be similar to that of the bottle-nosed dolphin.

Hominins

Although the complexity of a central nervous system, neural net may strongly influence the minimum brain size to enable the larger ganglia to think and conceive in the abstract, an apparent maximum size of 200 cm3, or 200 gm, is all that's needed to run any size animal regardless of its tissue variations.

Homo sapiens neanderthalensis

"Neanderthals (or Neandertals) are our closest extinct human relatives. [They may have been] a subspecies [Homo sapiens neanderthalensis]. Our well-known [...] fossil kin lived in Eurasia 200,000 to 30,000 years ago, in the Pleistocene Epoch. [...] they used tools, buried their dead and controlled fire, among other intelligent behaviors."[14]

"Neanderthals came to Europe some 300,000 years ago. They hunted big game with stone tools. Their territory spanned Europe and Asia. They left distinctive "Mousterian" artefacts."[15]

"Work on material from Italy seems to show human settlers pushing Neanderthals out (see maps). Mousterian tools were common there 45,000 years ago, when human-made Uluzzian material first appeared. By 44,000 years ago, humans were sharing Italy with a dwindling Neanderthal population. By 42,000 years ago, the Neanderthals were gone."[15]

"Around 39,000 years ago, a Neanderthal huddled in the back of a seaside cave at Gibraltar, safe from the hyenas, lions and leopards that might have prowled outside. Under the flickering light of a campfire, he or she used a stone tool to carefully etch what looks like a grid or a hashtag [in the image at the right] onto a natural platform of bedrock."[16]

"This was intentional — this was not somebody doodling or scratching on the surface."[17]

"Neanderthals might have behaved more like Homo sapiens than previously thought: They buried their dead, they used pigments and feathers to decorate their bodies, and they may have even organized their caves."[16]

"Art is something else — it's an indication of abstract thinking."[17]

"In Gorham's Cave, Finlayson and colleagues were surprised to find a series of deeply incised parallel and crisscrossing lines when they wiped away the dirt covering a bedrock surface. The rock had been sealed under a layer of soil that was littered with Mousterian stone tools (a style long linked to Neanderthals). Radiocarbon dating indicated that this soil layer was between 38,500 and 30,500 years old, suggesting the rock art buried underneath was created sometime before then."[16]

"Gibraltar is one of the most famous sites of Neanderthal occupation. At Gorham's Cave and its surrounding caverns, archaeologists have found evidence that Neanderthals butchered seals, roasted pigeons and plucked feathers off birds of prey. In other parts of Europe, Neanderthals lived alongside humans — and may have even interbred with them. But 40,000 years ago, the southern Iberian Peninsula was a Neanderthal stronghold."[16]

"Modern humans had not spread into the area yet."[17]

"More than 50 stone-tool incisions were needed to mimic the deepest line of the grid, and between 188 and 317 total strokes were probably needed to create the entire pattern."[16]

"It's very basic. It's very simple. It's not a Venus. It's not a bison. It's not a horse."[18]

"There is a huge difference between making three lines that any 3-year-old kid would be able to make and sculpting a Venus."[18]

"My own feeling is that if Neanderthals regularly used symbols, and given their longtime occupation throughout large parts of the Old World, we probably would have found clearer evidence by now."[19]

Scientists need "more than a few scratches — deliberate or not — to identify symbolic behavior on the part of Neanderthals."[19]

"Symbols, by definition, have meanings that are shared by a group of people, and because of that, they are often repeated. By itself, this is a unique example and without any intrinsic meaning … the question is not 'Could it be symbolic?' but rather 'Was it symbolic?' And to demonstrate that, it would be very important to have repeated examples."[19]

Neanderthals had an average brain size of 1500 cm3.[4] Another source puts brain sizes from three localities as Spy I 1,305 ml, Spy II 1,553 ml, and Djebel Ihroud I 1305 ml.[20]

Homo sapiens sapiens

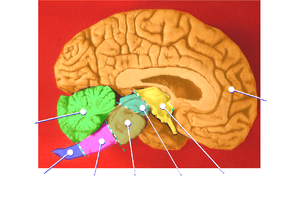

| Human brain midsagittal cut |

Cerebrum

Diencephalon

Midbrain

Pons

Medulla

Spinal cord

Cerebellum

└─┬─┴───┘

Brain stem

|

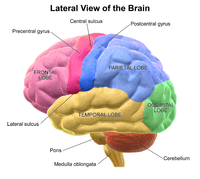

The image at the right shows the fit of a human brain into its skull with extension on the lower right to the spinal column.

The diagram at the left labels the various lobes of the human brain.

Below on the right is an animation that reveals brain lobe positioning relative to the skull.

An average brain weight for an adult human is about 1500 gms.[21] The volume varies substantially with individuals for an average of 1130 cm3 in women and 1260 cm3 in men.[22] Such a range is 1250-1450 gms.[4]

Homo erectus

""Peking Man," a human ancestor who lived in China between roughly 200,000 and 750,000 years ago, was a wood-working, fire-using, spear-hafting hominid ... these hominids, a form of Homo erectus, appear to have been quite meticulous about their clothing, using stone tools to soften and depress animal hides."[23]

"[S]ome of the oldest stone hand axes on Earth ... unearthed in Ethiopia ... date to 1.75 million years ago. ... fossilized H. erectus remains were also found at the same site ... These Aucheulean tools could be up to 7.8 inches (20 centimeters) long".[24]

"Javanese specimens of Homo erectus had brains about 860 cubic cm (52 cubic inches) large".[25] The Salè Homo erectus was 880 ml.[20]

Homo habilis

"[T]he hobbit [may have] evolved from Homo habilis, whose brains were only about 600 cubic cm (37 cubic inches)."[25]

Homo floresiensis

"The 18,000-year-old fossils of the extinct type of human officially known as Homo floresiensis were first discovered on the remote Indonesian island of Flores in 2003. Its squat, 3-foot-tall (1 meter) build led to the hobbit nickname."[25]

"[T]he hobbit's brain was larger than previously suggested — 426 cubic cm (nearly 26 cubic inches), instead of the commonly cited figure of 400 cubic cm. (The modern human brain is 1,300 cubic centimeters, or 79 cubic inches, large on average.)"[25]

Australopithecus afarensis

"Compared to the modern and extinct great apes, A. afarensis has reduced canines and molars, although they are still relatively larger than in modern humans. A. afarensis also has a relatively small brain size (~380–430 cm3) and a prognathic face (i.e. a face with forward projecting jaws)."[26]

Chimpanzees

The range of brain sizes for chimpanzees is 330-430 gms.[4]

The bonobos, an individual adult is in the image at the right, are an intelligent species Pan paniscus on Earth that probably have both the necessary and sufficient mental capacity to think and conceive in the abstract. Perhaps they can also use logic or at least reasoning.

Research

Hypothesis:

- There are, or have been, at least 23 species on Earth possessing at least as adults an abstract concept generator; i.e., the ability to think and conceive in the abstract.

- In order to conduct original research into the possible existence of abstract concept generators within complex neural networks or systems, an understanding of universals, control groups, and at least proof of concept is needed.

Control groups

The findings demonstrate a statistically systematic change from the status quo or the control group.

“In the design of experiments, treatments [or special properties or characteristics] are applied to [or observed in] experimental units in the treatment group(s).[27] In comparative experiments, members of the complementary group, the control group, receive either no treatment or a standard treatment.[28]"[29]

Proof of concept

Def. a “short and/or incomplete realization of a certain method or idea to demonstrate its feasibility"[30] is called a proof of concept.

Def. evidence that demonstrates that a concept is possible is called proof of concept.

The proof-of-concept structure consists of

- background,

- procedures,

- findings, and

- interpretation.[31]

See also

- Humans

References

- ↑ Teun A Van Dijk (1971). "Some problems of generative poetics". Poetics 2: 5-35. http://www.discourses.org/OldArticles/Some%20Problems%20of%20Generative%20Poetics.pdf. Retrieved 2014-07-21.

- 1 2 3 "abstraction, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 2 November 2014. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- ↑ WF Perrin, B Wursig, and JGM Thewissen (13 November 2013). "Sperm Whales (Physeter macrocephalus)". NOAA. Retrieved 2014-09-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gerhard Roth and Ursula Dicke (May 2005). "Evolution of the brain and intelligence". Trends in Cognitive Sciences 9 (5): 250-7. http://www.subjectpool.com/ed_teach/y3project/Roth2005_TICS_brain_size_and_intelligence.pdf. Retrieved 2014-09-23.

- 1 2 3 4 Raymond J. Tarpley and Sam H. Ridgway (1994). "Corpus Callosum Size in Delphinid Cetaceans". Brain Behav Evol 44: 156-65. http://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/113587. Retrieved 2014-09-23.

- ↑ DB Tower (August 1954). "Structural and functional organization of mammalian cerebral cortex; the correlation of neurone density with brain size; cortical neurone density in the fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus L.) with a note on the cortical neurone density in the Indian elephant". J Comp Neurol 101 (1): 19-51. PMID 13211853. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cne.901010103/full. Retrieved 2014-09-23.

- ↑ Laura Geggel (July 28, 2014). "Mammoths and Mastodons of the Ohio Valley Were Homebodies". LiveScience.com. Retrieved 2014-09-07.

- ↑ Brooke Crowley (July 28, 2014). "Mammoths and Mastodons of the Ohio Valley Were Homebodies". LiveScience.com. Retrieved 2014-09-07.

- 1 2 3 Eleftheria Palkopoulou (23 April 2015). "Genetic Scientists Sequence Complete Genomes of Two Woolly Mammoths". Sci-News. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- ↑ Love Dalén (23 April 2015). "Genetic Scientists Sequence Complete Genomes of Two Woolly Mammoths". Sci-News. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- 1 2 Hendrik Poinar (23 April 2015). "Genetic Scientists Sequence Complete Genomes of Two Woolly Mammoths". Sci-News. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- 1 2 Caro-Beth Stewart (June 26, 2012). "Building a Bigger Dolphin Brain". American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- ↑ Michael McGowen (June 26, 2012). "Building a Bigger Dolphin Brain". American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- ↑ Jessie Szalay (March 19, 2013). "Neanderthals: Facts About Our Extinct Human Relatives". livescience. Retrieved 2013-11-15.

- 1 2 Catherine Brahic (20 August 2014). "Neanderthal demise traced in unprecedented detail". New Scientist. Retrieved 2014-08-26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Megan Gannon (02 September 2014). "Cave Carving May Be 1st Known Example of Neanderthal Rock Art". LiveScience.com. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- 1 2 3 Stewart Finlayson (02 September 2014). "Cave Carving May Be 1st Known Example of Neanderthal Rock Art". LiveScience.com. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- 1 2 Jean-Jacques Hublin (02 September 2014). "Cave Carving May Be 1st Known Example of Neanderthal Rock Art". LiveScience.com. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- 1 2 3 Harold Dibble (02 September 2014). "Cave Carving May Be 1st Known Example of Neanderthal Rock Art". LiveScience.com. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- 1 2 Ralph L. Holloway (1981). "Volumetric and Asymmetry Determinations on Recent Hominid Endocasts: Spy I and II, Djebel Ihroud I, and the Salè Homo erectus Specimens, With Some Notes on Neandertal Brain Size". American Journal of Physical Anthropology 55: 385-93. http://www.columbia.edu/~rlh2/Spy1%262,IrhoudEndos.AJPA1981.pdf. Retrieved 2014-09-23.

- ↑ A. Parent, M.B. Carpenter (1995). "Ch. 1". Carpenter's Human Neuroanatomy. Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-683-06752-1.

- ↑ KP Cosgrove, CM Mazure, JK Staley (2007). "Evolving knowledge of sex differences in brain structure, function, and chemistry". Biol Psychiat 62 (8): 847–55. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.001. PMID 17544382. PMC 2711771. //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2711771/.

- ↑ Owen Jarus (December 31, 2012). "'Peking Man' Was a Fashion Plate". LiveScience. Retrieved 2013-01-05.

- ↑ Tia Ghose (January 28, 2013). "Did Rise of Ancient Human Ancestor Lead to New Stone Tools?". Yahoo! News. Retrieved 2013-02-02.

- 1 2 3 4 Charles Choi (April 17, 2013). "The Real 'Hobbit' Had Larger Brain Than Thought". Yahoo! News. Retrieved 2013-04-23.

- ↑ "Australopithecus afarensis, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. October 26, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ Klaus Hinkelmann, Oscar Kempthorne (2008). Design and Analysis of Experiments, Volume I: Introduction to Experimental Design (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-72756-9. http://books.google.com/?id=T3wWj2kVYZgC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ R. A. Bailey (2008). Design of comparative experiments. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68357-9. http://www.cambridge.org/uk/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521683579.

- ↑ "Treatment and control groups, In: Wikipedia". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. May 18, 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-31.

- ↑ "proof of concept, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. November 10, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ↑ Ginger Lehrman and Ian B Hogue, Sarah Palmer, Cheryl Jennings, Celsa A Spina, Ann Wiegand, Alan L Landay, Robert W Coombs, Douglas D Richman, John W Mellors, John M Coffin, Ronald J Bosch, David M Margolis (August 13, 2005). "Depletion of latent HIV-1 infection in vivo: a proof-of-concept study". Lancet 366 (9485): 549-55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67098-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1894952/. Retrieved 2012-05-09.

External links

- African Journals Online

- Bing Advanced search

- GenomeNet KEGG database

- Google Books

- Google scholar Advanced Scholar Search

- Home - Gene - NCBI

- JSTOR

- Lycos search

- NCBI All Databases Search

- Office of Scientific & Technical Information

- PsycNET

- PubChem Public Chemical Database

- Questia - The Online Library of Books and Journals

- SAGE journals online

- The SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System

- Scirus for scientific information only advanced search

- SIMBAD Astronomical Database

- SIMBAD Web interface, Harvard alternate

- SpringerLink

- Taylor & Francis Online

- WikiDoc The Living Textbook of Medicine

- Wiley Online Library Advanced Search

- Yahoo Advanced Web Search

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![]() This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

This is a research project at http://en.wikiversity.org

| |

Educational level: this is a research resource. |

| |

Resource type: this resource is an article. |

| |

Resource type: this resource contains a lecture or lecture notes. |

| |

Subject classification: this is an Anthropology resource. |

| |

Subject classification: this is a biology resource . |

| |

Subject classification: this is a genetics resource. |

| |

Subject classification: this is a humanities resource. |

| |

Subject classification: this is a psychology resource . |