Waves/Vectors

< WavesMath Tutorial -- Vectors

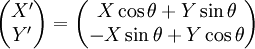

Figure 1: Displacement vectors in a plane.

Vector  represents the displacement of George from Mary, while vector

represents the displacement of George from Mary, while vector  represents the displacement of Paul from George. Vector

represents the displacement of Paul from George. Vector  represents the displacement of Paul from Mary and

represents the displacement of Paul from Mary and  . The quantities

. The quantities  ,

,  , etc., represent the Cartesian components of the vectors.

, etc., represent the Cartesian components of the vectors.

Before we can proceed further we need to explore the idea of a vector. A vector is a quantity which expresses both magnitude and direction. Graphically we represent a vector as an arrow. In typeset notation a vector is represented by a boldface character, while in handwriting an arrow is drawn over the character representing the vector.

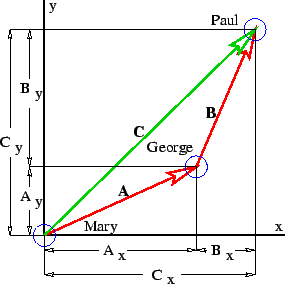

Figure 1 shows some examples of displacement vectors, i. e., vectors which represent the displacement of one object from another, and introduces the idea of vector addition. The tail of vector  is collocated with the head of vector

is collocated with the head of vector  , and the vector which stretches from the tail of

, and the vector which stretches from the tail of  to the head of

to the head of  is the sum of

is the sum of  and

and  , called

, called  in figure 1.

in figure 1.

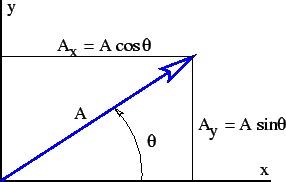

representing the orientation of a two dimensional vector.

representing the orientation of a two dimensional vector.

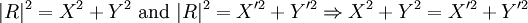

The quantities  ,

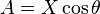

,  , etc., represent the Cartesian components of the vectors in figure 2. A vector can be represented either by its Cartesian components, which are just the projections of the vector onto the Cartesian coordinate axes, or by its direction and magnitude. The direction of a vector in two dimensions is generally represented by the counterclockwise angle of the vector relative to the

, etc., represent the Cartesian components of the vectors in figure 2. A vector can be represented either by its Cartesian components, which are just the projections of the vector onto the Cartesian coordinate axes, or by its direction and magnitude. The direction of a vector in two dimensions is generally represented by the counterclockwise angle of the vector relative to the  axis, as shown in figure 2. Conversion from one form to the other is given by the equations

axis, as shown in figure 2. Conversion from one form to the other is given by the equations

where  is the magnitude of the vector. A vector magnitude is sometimes represented by absolute value notation:

is the magnitude of the vector. A vector magnitude is sometimes represented by absolute value notation:  .

.

Notice that the inverse tangent gives a result which is ambiguous relative to adding or subtracting integer multiples of  . Thus the quadrant in which the angle lies must be resolved by independently examining the signs of

. Thus the quadrant in which the angle lies must be resolved by independently examining the signs of  and

and  and choosing the appropriate value of

and choosing the appropriate value of  .

.

To add two vectors,  and

and  , it is easiest to convert them to Cartesian component form. The components of the sum

, it is easiest to convert them to Cartesian component form. The components of the sum  are then just the sums of the components:

are then just the sums of the components:

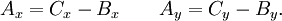

Subtraction of vectors is done similarly, e. g., if  , then

, then

A unit vector is a vector of unit length. One can always construct a unit vector from an ordinary vector by dividing the vector by its length:  . This division operation is carried out by dividing each of the vector components by the number in the denominator. Alternatively, if the vector is expressed in terms of length and direction, the magnitude of the vector is divided by the denominator and the direction is unchanged.

. This division operation is carried out by dividing each of the vector components by the number in the denominator. Alternatively, if the vector is expressed in terms of length and direction, the magnitude of the vector is divided by the denominator and the direction is unchanged.

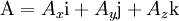

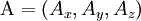

Unit vectors can be used to define a Cartesian coordinate system. Conventionally,  ,

,  , and

, and  indicate the

indicate the  ,

,  , and

, and  axes of such a system. Note that

axes of such a system. Note that  ,

,  , and

, and  are mutually perpendicular. Any vector can be represented in terms of unit vectors and its Cartesian components:

are mutually perpendicular. Any vector can be represented in terms of unit vectors and its Cartesian components:  . An alternate way to represent a vector is as list of components:

. An alternate way to represent a vector is as list of components:  . We tend to use the latter representation since it is somewhat more economical notation.

. We tend to use the latter representation since it is somewhat more economical notation.

There are two ways to multiply two vectors, yielding respectively what are known as the dot product and the cross product. The cross product yields another vector while the dot product yields a number. Here we will discuss only the dot product.

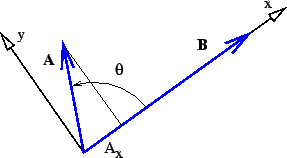

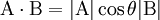

Figure 3: Definition sketch for dot product.

Figure 3: Definition sketch for dot product.

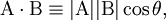

Given vectors  and

and  , the dot product of the two is defined

, the dot product of the two is defined

where  is the angle between the two vectors. An alternate expression for the dot product exists in terms of the Cartesian components of the vectors:

is the angle between the two vectors. An alternate expression for the dot product exists in terms of the Cartesian components of the vectors:

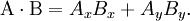

It is easy to show that this is equivalent to the cosine form of the dot product when the  axis lies along one of the vectors, as in figure 3. Notice in particular that

axis lies along one of the vectors, as in figure 3. Notice in particular that  , while

, while  and

and  . Thus,

. Thus,  in this case, which is identical to the form given above.

in this case, which is identical to the form given above.

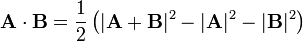

By the law of cosines we can also see that

which is an alternate coordinate-free expression for the dot product.

Figure 4: Definition figure for rotated coordinate system. The vector  has components

has components  and

and  in the unprimed coordinate system and components

in the unprimed coordinate system and components  and

and  in the primed coordinate system.

in the primed coordinate system.

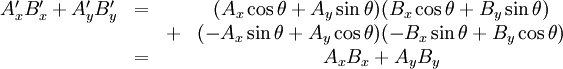

All that remains to be proven for equation (2.6) to hold in general is to show that it yields the same answer regardless of how the Cartesian coordinate system is oriented relative to the vectors. To do this, we must show that  , where the primes indicate components in a coordinate system rotated from the original coordinate system.

, where the primes indicate components in a coordinate system rotated from the original coordinate system.

This can be shown nearly instantly by applying the pythagorean theorem. Due to the fact that R is invariant and represents the hypotenuse for both triangles (X, X', Y and Y') we can conclude:

Since the dot product can be written solely in terms of magnitudes, as we did above, if the magnitude of a vector is invariant the dot product of two vectors must also be invariant.

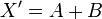

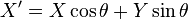

To deduce a general formula for X' and Y' you will have to do a bit more thinking:

Figure 2.4 shows the vector  resolved in two coordinate systems rotated with respect to each other. From this figure it is clear that

resolved in two coordinate systems rotated with respect to each other. From this figure it is clear that  . Focusing on the shaded triangles, we see that

. Focusing on the shaded triangles, we see that  and

and  . Thus, we find

. Thus, we find  . Similar reasoning shows that

. Similar reasoning shows that  (Just imagine to rotate the constructs in the image further 90° without changing the axis-names. You will instantly notice that in the second quadrant X is negative while Y positive).

(Just imagine to rotate the constructs in the image further 90° without changing the axis-names. You will instantly notice that in the second quadrant X is negative while Y positive).

Thus, the new and old coordinates are related by

This is true of the position vector. We can use it to extend the notion of vector to concepts other than position by stating that a pair of numbers is a vector if and only if its values change in exactly this way under rotation.

Substituting this relation into our earlier expression for the dot product and using the trigonometric identity  results in

results in

which proves the complete equivalence of the two forms of the dot product quoted above. (Multiply out the above expression to verify this.)

A numerical quantity which doesn't depend on which coordinate system is being used is called a scalar. The dot product of two vectors is a scalar. However, the components of a vector, taken individually, are not scalars, since the components change as the coordinate system changes. Since the laws of physics cannot depend on the choice of coordinate system being used, we insist that physical laws be expressed in terms of scalars and vectors, but not in terms of the components of vectors.

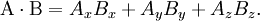

In three dimensions the cosine form of the dot product remains the same, while the component form is