Discrete Mathematics/Set theory

< Discrete MathematicsSet Theory starts very simply: it examines whether an object belongs, or does not belong, to a set of objects which has been described in some non-ambiguous way. From this simple beginning, an increasingly complex (and useful!) series of ideas can be developed, which lead to notations and techniques with many varied applications.

Definition of a Set

The definition of a set sounds very vague at first. A set can be defined as a collection of things that are brought together because they obey a certain rule.

These 'things' may be anything you like: numbers, people, shapes, cities, bits of text ..., literally anything.

The key fact about the 'rule' they all obey is that it must be well-defined. In other words, it enables us to say for sure whether or not a given 'thing' belongs to the collection. If the 'things' we're talking about are English words, for example, a well-defined rule might be:

- '... has 5 or more letters'

A rule which is not well-defined (and therefore couldn't be used to define a set) might be:

- '... is hard to spell'

Elements

A 'thing' that belongs to a given set is called an 'element' of that set. For example:

- Henry VIII is an element of the set of Kings of England.

Notation

Curly brackets are used to stand for the phrase 'the set of ...'. These braces can be used in various ways. For example:

- We may list the elements of a set:

- We may list the elements of a set:

- We may describe the elements of a set:

- We may describe the elements of a set:

- We may use an identifier (the letter for example) to represent a typical element, a symbol to stand for the phrase 'such that', and then the rule or rules that the identifier must obey:

- or

- We may use an identifier (the letter for example) to represent a typical element, a symbol to stand for the phrase 'such that', and then the rule or rules that the identifier must obey:

The last way of writing a set - called set comprehension notation - can be generalized as:

- , where is a statement (technically a propositional function) about and the set is the collection of all elements for which is true.

The symbol is used as follows:

- means 'is an element of ...'. For example:

- means 'is not an element of ...'. For example:

A set can be finite:

... or infinite:

(Note the use of the ellipsis to indicate that the sequence of numbers continues indefinitely.)

Sets will usually be denoted using upper case letters: , , ...

Elements will usually be denoted using lower case letters: , , ...

Set Operations

Universal Set

The set of all the 'things' currently under discussion is called the universal set (or sometimes, simply the universe). It is denoted by U.

The universal set doesn’t contain everything in the whole universe. On the contrary, it restricts us to just those things that are relevant at a particular time. For example, if in a given situation we’re talking about numeric values – quantities, sizes, times, weights, or whatever – the universal set will be a suitable set of numbers (see below). In another context, the universal set may be {alphabetic characters} or {all living people}, etc.

Empty set

The set containing no elements at all is called the null set, or empty set. It is denoted by a pair of empty braces: or by the symbol .

It may seem odd to define a set that contains no elements. Bear in mind, however, that one may be looking for solutions to a problem where it isn't clear at the outset whether or not such solutions even exist. If it turns out that there isn't a solution, then the set of solutions is empty.

For example:

- If then .

- If then .

Operations on the empty set

Operations performed on the empty set (as a set of things to be operated upon) can also be confusing. (Such operations are nullary operations.) For example, the sum of the elements of the empty set is zero, but the product of the elements of the empty set is one (see empty product). This may seem odd, since there are no elements of the empty set, so how could it matter whether they are added or multiplied (since “they” do not exist)? Ultimately, the results of these operations say more about the operation in question than about the empty set. For instance, notice that zero is the identity element for addition, and one is the identity element for multiplication.

Some special sets of numbers

Several sets are used so often, they are given special symbols.

The natural numbers

The 'counting' numbers (or whole numbers) starting at 1, are called the natural numbers. This set is sometimes denoted by N. So N = {1, 2, 3, ...}

Note that, when we write this set by hand, we can't write in bold type so we write an N in blackboard bold font:

Integers

All whole numbers, positive, negative and zero form the set of integers. It is sometimes denoted by Z. So Z = {..., -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, ...}

In blackboard bold, it looks like this:

Real numbers

If we expand the set of integers to include all decimal numbers, we form the set of real numbers. The set of reals is sometimes denoted by R.

A real number may have a finite number of digits after the decimal point (e.g. 3.625), or an infinite number of decimal digits. In the case of an infinite number of digits, these digits may:

- recur; e.g. 8.127127127...

- ... or they may not recur; e.g. 3.141592653...

In blackboard bold:

Rational numbers

Those real numbers whose decimal digits are finite in number, or which recur, are called rational numbers. The set of rationals is sometimes denoted by the letter Q.

A rational number can always be written as exact fraction p/q; where p and q are integers. If q equals 1, the fraction is just the integer p. Note that q may NOT equal zero as the value is then undefined.

- For example: 0.5, -17, 2/17, 82.01, 3.282828... are all rational numbers.

In blackboard bold:

Irrational numbers

If a number can't be represented exactly by a fraction p/q, it is said to be irrational.

- Examples include: √2, √3, π.

Set Theory Exercise 1

Click the link for Set Theory Exercise 1

Relationships between Sets

We’ll now look at various ways in which sets may be related to one another.

Equality

Two sets A and B are said to be equal if and only if they have exactly the same elements. In this case, we simply write:

- A = B

Note two further facts about equal sets:

- The order in which elements are listed does not matter.

- If an element is listed more than once, any repeat occurrences are ignored.

So, for example, the following sets are all equal:

- {1, 2, 3} = {3, 2, 1} = {1, 1, 2, 3, 2, 2}

(You may wonder why one would ever come to write a set like {1, 1, 2, 3, 2, 2}. You may recall that when we defined the empty set we noted that there may be no solutions to a particular problem - hence the need for an empty set. Well, here we may be trying several different approaches to solving a problem, some of which in fact lead us to the same solution. When we come to consider the distinct solutions, however, any such repetitions would be ignored.)

// Actually in the set theory, there is not expression like these ({1, 1, 2, 3, 2, 2}). All elements must be unique.

Subsets

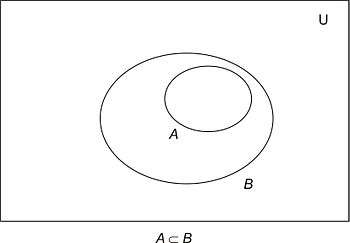

If all the elements of a set A are also elements of a set B, then we say that A is a subset of B, and we write:

- A ⊆ B

For example:

In the examples below:

- If T = {2, 4, 6, 8, 10} and E = {even integers}, then T ⊆ E

- If A = {alphanumeric characters} and P = {printable characters}, then A ⊆ P

- If Q = {quadrilaterals} and F = {plane figures bounded by four straight lines}, then Q ⊆ F

Notice that A ⊆ B does not imply that B must necessarily contain extra elements that are not in A; the two sets could be equal – as indeed Q and F are above. However, if, in addition, B does contain at least one element that isn’t in A, then we say that A is a proper subset of B. In such a case we would write:

- A ⊂ B

In the examples above:

- E contains ... -4, -2, 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, ... , so T ⊂ E

- P contains $, ;, &, ..., so A ⊂ P

But Q and F are just different ways of saying the same thing, so Q = F

The use of ⊂ and ⊆ is clearly analogous to the use of < and ≤ when comparing two numbers.

Notice also that every set is a subset of the universal set, and the empty set is a subset of every set.

(You might be curious about this last statement: how can the empty set be a subset of anything, when it doesn’t contain any elements? The point here is that for every set A, the empty set doesn’t contain any elements that aren't in A. So ø ⊆ A for all sets A.)

Finally, note that if A ⊆ B and B ⊆ A then A and B must contain exactly the same elements, and are therefore equal. In other words:

- If A ⊆ B and B ⊆ A then A = B

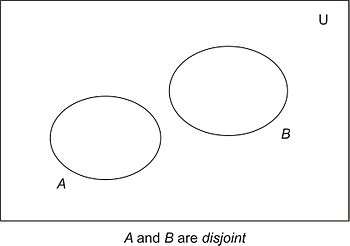

Disjoint

Two sets are said to be disjoint if they have no elements in common. For example:

- If A = {even numbers} and B = {1, 3, 5, 11, 19}, then A and B are disjoint sets

Venn Diagrams

A Venn diagram can be a useful way of illustrating relationships between sets.

In a Venn diagram:

- The universal set is represented by a rectangle. Points inside the rectangle represent elements that are in the universal set; points outside represent things not in the universal set. You can think of this rectangle, then, as a 'fence' keeping unwanted things out - and concentrating our attention on the things we're talking about.

- Other sets are represented by loops, usually oval or circular in shape, drawn inside the rectangle. Again, points inside a given loop represent elements in the set it represents; points outside represent things not in the set.

On the left, the sets A and B are disjoint, because the loops don't overlap.

On the right A is a subset of B, because the loop representing set A is entirely enclosed by loop B.

Venn diagrams: Worked Examples

Example 1

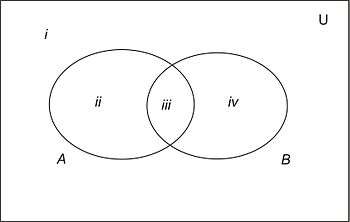

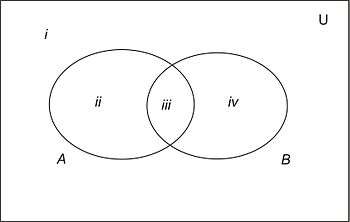

Fig. 3 represents a Venn diagram showing two sets A and B, in the general case where nothing is known about any relationships between the sets.

Note that the rectangle representing the universal set is divided into four regions, labelled i, ii, iii and iv.

What can be said about the sets A and B if it turns out that:

- (a) region ii is empty?

- (b) region iii is empty?

(a) If region ii is empty, then A contains no elements that are not in B. So A is a subset of B, and the diagram should be re-drawn like Fig 2 above.

(b) If region iii is empty, then A and B have no elements in common and are therefore disjoint. The diagram should then be re-drawn like Fig 1 above.

Example 2

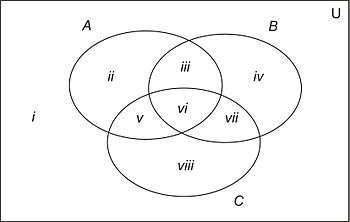

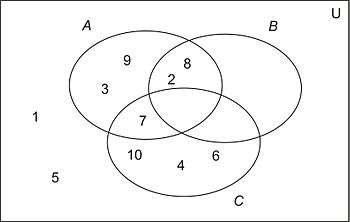

- (a) Draw a Venn diagram to represent three sets A, B and C, in the general case where nothing is known about possible relationships between the sets.

- (b) Into how many regions is the rectangle representing U divided now?

- (c) Discuss the relationships between the sets A, B and C, when various combinations of these regions are empty.

(a) The diagram in Fig. 4 shows the general case of three sets where nothing is known about any possible relationships between them.

(b) The rectangle representing U is now divided into 8 regions, indicated by the Roman numerals i to viii.

(c) Various combinations of empty regions are possible. In each case, the Venn diagram can be re-drawn so that empty regions are no longer included. For example:

- If region ii is empty, the loop representing A should be made smaller, and moved inside B and C to eliminate region ii.

- If regions ii, iii and iv are empty, make A and B smaller, and move them so that they are both inside C (thus eliminating all three of these regions), but do so in such a way that they still overlap each other (thus retaining region vi).

- If regions iii and vi are empty, 'pull apart' loops A and B to eliminate these regions, but keep each loop overlapping loop C.

- ...and so on. Drawing Venn diagrams for each of the above examples is left as an exercise for the reader.

Example 3

The following sets are defined:

- U = {1, 2, 3, …, 10}

- A = {2, 3, 7, 8, 9}

- B = {2, 8}

- C = {4, 6, 7, 10}

Using the two-stage technique described below, draw a Venn diagram to represent these sets, marking all the elements in the appropriate regions.

The technique is as follows:

- Draw a 'general' 3-set Venn diagram, like the one in Example 2.

- Go through the elements of the universal set one at a time, once only, entering each one into the appropriate region of the diagram.

- Re-draw the diagram, if necessary, moving loops inside one another or apart to eliminate any empty regions.

Don't begin by entering the elements of set A, then set B, then C – you'll risk missing elements out or including them twice!

Solution

After drawing the three empty loops in a diagram looking like Fig. 4 (but without the Roman numerals!), go through each of the ten elements in U - the numbers 1 to 10 - asking each one three questions; like this:

First element: 1

- Are you in A? No

- Are you in B? No

- Are you in C? No

A 'no' to all three questions means that the number 1 is outside all three loops. So write it in the appropriate region (region number i in Fig. 4).

Second element: 2

- Are you in A? Yes

- Are you in B? Yes

- Are you in C? No

Yes, yes, no: so the number 2 is inside A and B but outside C. Goes in region iii then.

...and so on, with elements 3 to 10.

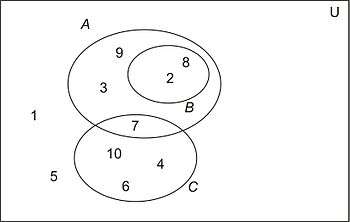

The resulting diagram looks like Fig. 5.

The final stage is to examine the diagram for empty regions - in this case the regions we called iv, vi and vii in Fig. 4 - and then re-draw the diagram to eliminate these regions. When we've done so, we shall clearly see the relationships between the three sets.

So we need to:

- pull B and C apart, since they don't have any elements in common.

- push B inside A since it doesn't have any elements outside A.

The finished result is shown in Fig. 6.

The regions in a Venn Diagram and Truth Tables

Perhaps you've realized that adding an additional set to a Venn diagram doubles the number of regions into which the rectangle representing the universal set is divided. This gives us a very simple pattern, as follows:

- With one set loop, there will be just two regions: the inside of the loop and its outside.

- With two set loops, there'll be four regions.

- With three loops, there'll be eight regions.

- ...and so on.

It's not hard to see why this should be so. Each new loop we add to the diagram divides each existing region into two, thus doubling the number of regions altogether.

| In A? | In B? | In C? |

|---|---|---|

| Y | Y | Y |

| Y | Y | N |

| Y | N | Y |

| Y | N | N |

| N | Y | Y |

| N | Y | N |

| N | N | Y |

| N | N | N |

But there's another way of looking at this, and it's this. In the solution to Example 3 above, we asked three questions of each element: Are you in A? Are you in B? and Are you in C? Now there are obviously two possible answers to each of these questions: yes and no. When we combine the answers to three questions like this, one after the other, there are then 23 = 8 possible sets of answers altogether. Each of these eight possible combinations of answers corresponds to a different region on the Venn diagram.

The complete set of answers resembles very closely a Truth Table - an important concept in Logic, which deals with statements which may be true or false. The table on the right shows the eight possible combinations of answers for 3 sets A, B and C.

You'll find it helpful to study the patterns of Y's and N's in each column.

- As you read down column C, the letter changes on every row: Y, N, Y, N, Y, N, Y, N

- Reading down column B, the letters change on every other row: Y, Y, N, N, Y, Y, N, N

- Reading down column A, the letters change every four rows: Y, Y, Y, Y, N, N, N, N

Set Theory Exercise 2

Click link for Set Theory Exercise 2

Operations on Sets

Just as we can combine two numbers to form a third number, with operations like 'add', 'subtract', 'multiply' and 'divide', so we can combine two sets to form a third set in various ways. We'll begin by looking again at the Venn diagram which shows two sets A and B in a general position, where we don't have any information about how they may be related.

| In A? | In B? | Region |

|---|---|---|

| Y | Y | iii |

| Y | N | ii |

| N | Y | iv |

| N | N | i |

The first two columns in the table on the right show the four sets of possible answers to the questions Are you in A? and Are you in B? for two sets A and B; the Roman numerals in the third column show the corresponding region in the Venn diagram in Fig. 7.

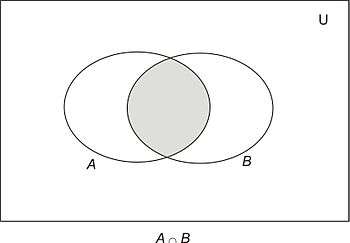

Intersection

Region iii, where the two loops overlap (the region corresponding to 'Y' followed by 'Y'), is called the intersection of the sets A and B. It is denoted by A ∩ B. So we can define intersection as follows:

- The intersection of two sets A and B, written A ∩ B, is the set of elements that are in A and in B.

(Note that in symbolic logic, a similar symbol, , is used to connect two logical propositions with the AND operator.)

For example, if A = {1, 2, 3, 4} and B = {2, 4, 6, 8}, then A ∩ B = {2, 4}.

We can say, then, that we have combined two sets to form a third set using the operation of intersection.

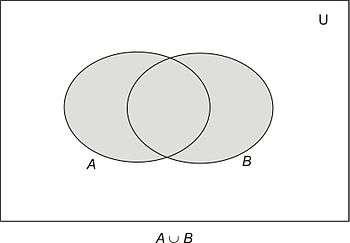

Union

In a similar way we can define the union of two sets as follows:

- The union of two sets A and B, written A ∪ B, is the set of elements that are in A or in B (or both).

The union, then, is represented by regions ii, iii and iv in Fig. 7.

(Again, in logic a similar symbol, , is used to connect two propositions with the OR operator.)

- So, for example, {1, 2, 3, 4} ∪ {2, 4, 6, 8} = {1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8}.

You'll see, then, that in order to get into the intersection, an element must answer 'Yes' to both questions, whereas to get into the union, either answer may be 'Yes'.

The ∪ symbol looks like the first letter of 'Union' and like a cup that will hold a lot of items. The ∩ symbol looks like a spilled cup that won't hold a lot of items, or possibly the letter 'n', for i'n'tersection. Take care not to confuse the two.

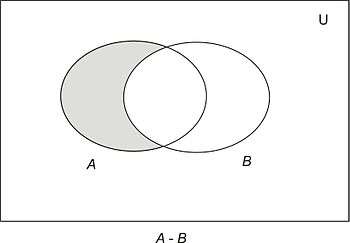

Difference

- The difference of two sets A and B (also known as the set-theoretic difference of A and B, or the relative complement of B in A) is the set of elements that are in A but not in B.

This is written A - B, or sometimes A \ B.

The elements in the difference, then, are the ones that answer 'Yes' to the first question Are you in A?, but 'No' to the second Are you in B?. This combination of answers is on row 2 of the above table, and corresponds to region ii in Fig.7.

- For example, if A = {1, 2, 3, 4} and B = {2, 4, 6, 8}, then A - B = {1, 3}.

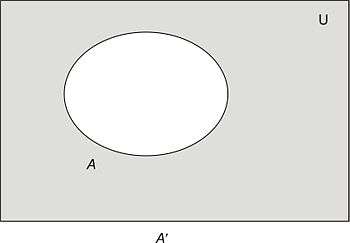

Complement

So far, we have considered operations in which two sets combine to form a third: binary operations. Now we look at a unary operation - one that involves just one set.

- The set of elements that are not in a set A is called the complement of A. It is written A′ (or sometimes AC, or ).

Clearly, this is the set of elements that answer 'No' to the question Are you in A?.

- For example, if U = N and A = {odd numbers}, then A′ = {even numbers}.

Notice the spelling of the word complement: its literal meaning is 'a complementary item or items'; in other words, 'that which completes'. So if we already have the elements of A, the complement of A is the set that completes the universal set.

Properties of set operations

1. Commutative

2. Associative

3. Distributive

4. Special properties of complements

5. De Morgan's Law

Summary

Intersection: things that are in A and in B |

Union: things that are in A or in B (or both) |

Difference: things that are in A and not in B |

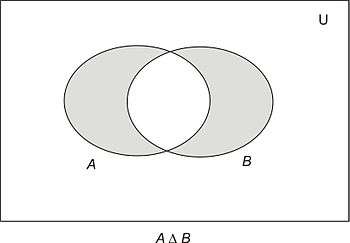

Symmetric Difference: things that are in A or in B but not both |

Complement: things that are not in A |

Cardinality

Finally, in this section on Set Operations we look at an operation on a set that yields not another set, but an integer.

- The cardinality of a finite set A, written | A | (sometimes #(A) or n(A)), is the number of (distinct) elements in A. So, for example:

- If A = {lower case letters of the alphabet}, | A | = 26.

Generalized set operations

If we want to denote the intersection or union of n sets, A1, A2, ..., An (where we may not know the value of n) then the following generalized set notation may be useful:

- A1 ∩ A2 ∩ ... ∩ An = Ai

- A1 ∪ A2 ∪ ... ∪ An = Ai

In the symbol Ai, then, i is a variable that takes values from 1 to n, to indicate the repeated intersection of all the sets A1 to An.

Set Theory Exercise 3

Click link for Set Theory Exercise 3 A={x I x is a lower case letter

Set Theory Page 2

Set Theory continues on Page 2.

Previous topic: Introduction | Contents:Discrete Mathematics | Next topic: Functions and relations