Conlang/Advanced/Grammar/Government/Binding theory

< Conlang < Advanced < Grammar < GovernmentBinding Theory

Binding theory is an attempt to account for certain phenomena involving pronouns and anaphors by using the structural framework we’ve developed up to this point. To understanding where this theory comes from it’s important first to understand what these kinds of words do that makes them so special and how they’re set apart from normal nouns.

Normal nouns are what’re called R-expressions (“r” for “referencing”). The have meaning derived from their reference to things outside of the words of the sentence, things in the world (e.g. “the tree”, “a car”). Pronouns, on the other hand, derive meaning by referring to other words in the sentence (to R-expressions), or from context, etc. (e.g. “he”, “her”, “they”). Finally, anaphors get their meaning only from R-expressions in the sentence (e.g. “itself”, “ourselves”).

We can find examples of special pronoun and anaphor behavior in these stunningly ungrammatical sentences:

- 1) *Itself bit the dog.

- 2) *He saw John. (where “he” refers to John)

So the question is why are these ungrammatical, and to find that out we need to determine what differences we can find between grammatical and ungrammatical examples.

Coreference

The first thing to introduce is a way of indicating whether or not two phrases refer to the same entity in the world. We’ll do this by using a unique subscript letter after the word or phrase for each unique entity.

- 3) [The dog]i bit [the man]j.

- 4) [Bob]i gave [Maria]j [the book]k.

- 5) [John]i thinks that [he]j likes [apple pie]k.

- 6) [Francine]i saw [herself]i in [the mirror]j.

This indexing allows us to note when two phrases refer to the same entity by identifying the same subscript on each phrase. By possessing the same index, that is, by being coindexed, we can determine that they corefer to the same entity.

Secondly, a simple notion of giving meaning is required. We’ll call a phrase an antecedent if it gives meaning to another phrase.

Binding

We can now explore some examples of grammatical and ungrammatical sentences to find some initial similarities and differences.

- 7) Johni saw himselfi in the mirror.

- 8) [Johni’s dog]j saw himselfj in the mirror.

- 9) *[Johni’s dog]j saw himselfi in the mirror.

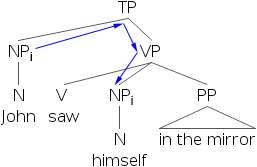

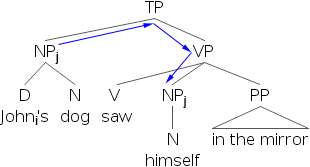

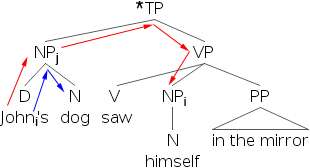

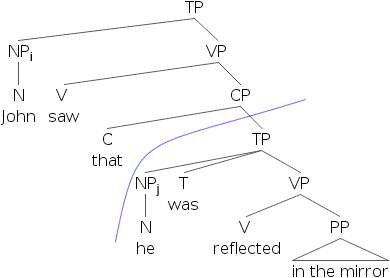

By examining the structure we find that the anaphor himself can’t corefer with an R-expressing that’s contained within another phrase that’s in subject position. If we examine the tree diagrams below, we’ll find that in the grammatical situations, the antecedents always c-command the anaphor.

- 10)

- 11)

- 12)

We can now define binding:

- 13) A node X binds a node Y if and only if X c-commands Y, and both X and Y corefer.

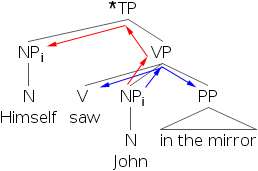

In 7-9, the sentence is grammatical only when the anaphor is bound by its antecedent. If this is general, then we should find cases where an anaphor binds its antecent to be ungrammatical.

- 14)

Since these are all ungrammatical, let’s make a rule out of this.

- 15) Principle A: An anaphor must be bound by its antecedent.

Domains

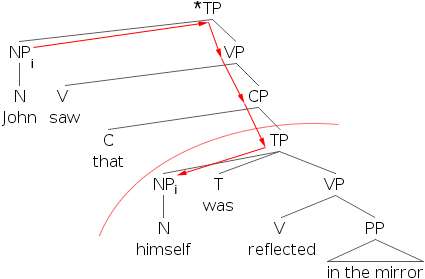

If English were as simple as that we’d be finished with binding, but unfortunately English isn’t that simple. We can easily find examples where an anaphor is bound by its antecedent but the sentence is still ungrammatical.

- 16)

In order to account for this we have to introduce the concept of a binding domain. Simply, a binding domain is the clause (TP) that contains the anaphor. What we notice about (16), now, is that the antecedent is outside of the binding domain of the anaphor. We can make a revision to Principle A to include a locality constraint (a rule that involves nearness).

- 17) Principle A (v.2): An anaphor must be bound by its antecedent within its binding domain.

For now this theory will suffice, but in the advanced syntax tutorial we’ll look at some easy-to-find examples of binding within a binding domain that still ungrammatical, and we’ll see how we can revise our theory to make it fit better.

Binding Pronouns

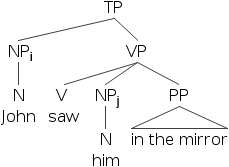

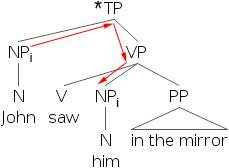

The behavior of pronouns turns out to be the reverse of anaphors. Consider these sentences:

- 18) Johni saw himj in the mirror.

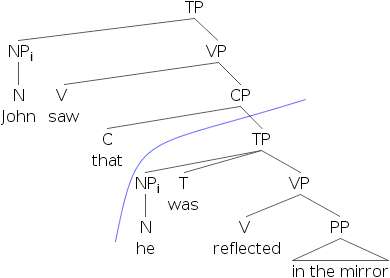

- 19) *Johni saw himi in the mirror.

- 20) Johni saw that hei was reflected in the mirror.

- 21) Johni saw that hej was reflected in the mirror.

- 22)

- 23)

- 24)

- 25)

In (18), the pronoun is unbound (or free), but in (19) the pronoun is bound. Looking at embedded clauses we find that if the pronoun is in an embedded clause, that is, a different binding domain, then the sentence is grammatical regardless of coreference. In the grammatical cases the pronoun is free within its binding domain, and in the ungrammatical cases it’s bound. We can make a second rule from this.

- 26) Principle B: A pronoun must be free in its binding domain.

Binding R-expressions

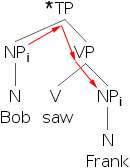

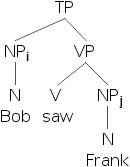

The last of the set to deal with, after anaphors and pronouns, is R-expressions, the whole set of nouns and phrases that aren’t anaphors nor pronouns. At first it seems like we shouldn’t need to describe where these can go at all, given our previous rules, but we can find perfectly ungrammatical sentences that don’t break either Principle A or B.

- 27) *Hei bit Fidoi.

- 28) *Bobi saw Franki.

- 29) Hei bit Fidoj.

- 30) Bobi saw Frankj.

- 31)

- 32)

- 33)

- 34)

In these situations, what we notice is that the sentence is ungrammatical only when the R-expression is bound. We can make a third rule now.

- 35) Principle C: An R-expression must be free.

With binding we now have a fairly complete way to describe many of the behaviors of language, in terms of structure, and we can begin to look at some of the things we can do with this knowledge.