Bicycles/Maintenance and Repair/Cables and Housings

< Bicycles < Maintenance and RepairGeneral

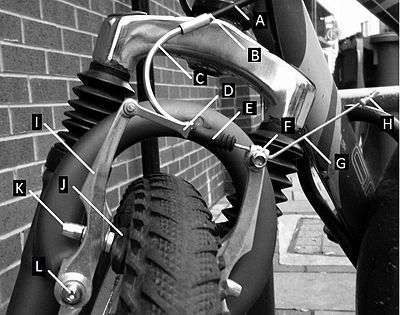

A. Cable Housing. B. Housing End Ferrule. C. Noodle. D. Housing Detent.

E. Rubber Boot. F. Cable Clamp. G. Cable Tail. H. Cable Cap.

I. Brake Arm J. Brake Block (Pad). K. Block Setting Screw. L. Arm Mounting Bolt.

Both cable and cable housings are used for nearly all braking and gear shifting, and this installation method greatly simplifies the running of cables in the modern bicycle. This use of an inner steel wire in an outer housing is referred to as a Bowden cable, after its inventor. Although some bicycles manage with just a bare inner wire in those places where the cables run straight, all other parts of the cable, and in particular those that might bend while riding, need to be fitted with housings.

In this context the term cable is intended to mean the inner-wire, the steel wire that attaches brake levers to brakes, and shifters to derailleurs. The housing is the flexible outer-tubing that surrounds the cable and acts as a conduit for it. The terms cabling and cable run refer to the Bowden cable as a whole. Perhaps surprisingly, and despite looking just like a plastic tube, a housing is in fact steel-reinforced along its entire length.

How Cable Housings Work

Cable housings always have both of their ends fixed. Fixed in this sense means pressed loosely against the screw-end of a barrel adjuster, or fixed hard into a part of the frame called a cable-stop. Brake housings are also made to terminate hard against one of the two brake arms, with the inner cable continuing to the other brake arm. That is to say, brake gaps depend on the difference in length between the inner cable and its housing.

In the case of a run to a derailleur, the housing abuts with the derailleur's static part and the cable runs on to rotate the moving parts of the shifting gear. A similar argument to the one for brakes applies in that it is the difference between the effective housing length and the inner cable's length that sets the exact degree of operation, (rotation in this case).

Although flexible, a housing is not easily deformed by the action of the cable within it. In braking, for example, the tendency of the cable is to deform the housing in the front cable route, but this is prevented by the housing's longitudinal reinforcement, (the steel wires along its length). The housing has more rigidity than the steel cable itself. To illustrate this point, it will be noticed during even hard braking that the housing loop on the handlebars does not change its shape. That is to say, although flexible, a housing behaves as if were a rigid conduit, and the overall cable pull is noted only at the housing's end, where the brakes or derailleur are located.

Clearly there are two ways to affect the length difference between the cable and its housing. The simplest way is to operate the brake lever or gear shifter. These affect the length of cables and the equipment attached to them respond accordingly, while the housing length remains constant. The other method, used for fine adjustments only, acts on the effective housing length.

Because the housing resists length changes, its length can only be changed by an additional in-line element; it is called a barrel-adjuster. In fact, a barrel adjuster should be thought of as an extension of its associated section of cable housing. It is used when only a few millimeters of adjustment is required. Continuing with the brake example: Recall that one end of a brake housing rests in the end of the barrel-adjuster, and the other elsewhere. When the looped cable run at the handlebars is extended by unscrewing the brake's barrel adjuster, then it follows that a few millimeters of cable must also enter that section to occupy it. In fact, the cable moves into the housing's end (at the brakes) to achieve this, with the result that the attached brake arm is pulled inward. The housing is effectively lengthened by unscrewing the barrel-adjuster, and this increasing of the housing length with respect to cable length reduces the brake gaps. The converse action occurs when the housing is effectively shortened; the barrel-adjuster is screwed in to increase the brake gaps.

It is perhaps of interest to note that some housings are installed with two sections and a bare cable between them. That is to say, the section of housing at the handlebar's barrel adjuster runs to a fixed point on the frame, called a cable-stop. Then the inner wire runs on as a bare cable, and through another housing-end that is also fixed in a cable-stop. That second housing then ends at the brake arms or derailleur in the usual way. In this case the principle remains the same as for a single housing, where sections without barrel-adjusters act merely to guide the cable and avoid resistance at transitions. Sections that are straight and lack barrel-adjusters need not have any housings at all.

Sometimes there are two barrel-adjusters in a single cable run, where the second is located on the fixed part of a derailleur. The adjustments of the two are additive, where both can affect the tension. They behave identically in their cable lengthening and shortening behaviour. Note the emphasis in this page on ferrules making a loose fit in the ends of barrel-adjusters. If a ferrule there made a tight fit then the entire housing would twist when the barrel was turned, so confounding the effort.

During the normal operation of shifters and brake levers the cables move in and out of the housings. In the case of a shifter, the cable is pulled-in or extended by only a few millimeters at a time; about 2.3mm for Shimano 10-speeds up to 4.5mm for SRAM 7-speed 1:1 GripShifts. Brake cable also moves only a few millimeters, although it is often more than the 2mm or so needed to close the brake gaps, because of the leverage effect of the brake arms. If, during these operations, the cable housings were also to change in length, brakes might bind and shifting would become uncertain. Housings of good quality are manufactured to avoid casual lengthening, and are sometimes described as incompressible. However, the use of such an expression does not in itself guarantee that a housing is suitable for the task, so the best approach is to use only those products that are stated by the manufacturer as intended for the specific purpose.

Cabling Components

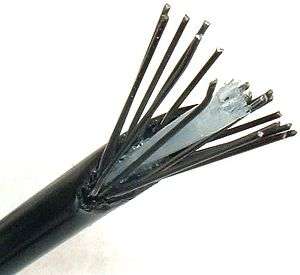

The common parts of a cable installation are these. A steel cable, consisting of several twisted wires runs the entire length of the cable housing and is usually contained in an inner-sheath for its protection and improved lubrication. The inner-sheath and its cable are housed within a steel-reinforced plastic tube.

Inner Wires

- Pre-stretched: Some inner wires are sold as pre-stretched so that they do not give rise to so much need for adjustment after installation. It is usual for other cables to stretch slightly, especially when they are new, though this just requires an occasional barrel-adjustment.

- Coatings: Inner wires are sometimes coated with TEFLON, to protect them against rusting, but because cables in housings are exposed only at their ends, this feature is useful mainly for bikes with bare cable runs. If cable ends are to be soldered to avoid fraying, any such coatings should first be removed by scraping.

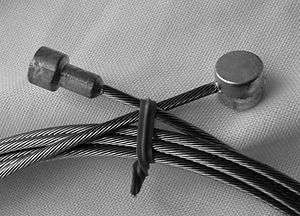

- Cable end terminals (anchors): The steel cables have welded end pieces (see image) that are shaped to fit into slots in shifters or brake levers and because cables are not interchangeable as to their purpose, there are three main types of inner-cable sold. A brake cable has either a barrel-shaped end, for bikes without drop-handlebars, or a pear-shaped end for the racing types with drop-handlebars. Cables for shifters have a button-shaped end. The free end of a cable is usually welded so that the wires cannot fray while the cable is being threaded through its housings. Some cables for brakes have a barrel at one end and a pear-termination at the other so that the user can discard the one that is not needed. These latter types are referred to as universal though the term is also used to describe some products that contain a complete brake or shifting kit that is long enough to fit most bikes.

- Thickness: Steel cables for brakes and shifting are usually of between 1.1 and 1.5mm diameter, and even the thinnest of such cables has a carrying strength in excess of 250lbs.

- Cable caps: These are small metallic pieces (see image) that fit over the open cable ends to prevent fraying. They are usually crimped with pliers, though some can be soldered. Alternatives to these include spoke caps and lead fishing weights. Do not confuse these with ferrules: ferrules fit onto cable housings while end-caps fit onto the free ends of steel cables.

- Lubrication: Most modern housings have inner sleeves that are pre-lubricated, so additional lubrication is rarely needed. If it is considered necessary, then adding a little light machine oil, (bicycle oil), to the cable at the time of assembly, or at the points where cables enter housings will have the desired effect.

Housing Types

- For Brakes: The main product for brakes is made with reinforcement in a continuous spiral with its coils very close together. This structure is useful for brake housings since it is stronger than housing with longitudinal reinforcement. It is not necessarily the least compressible but it wins on strength alone where safety is the most serious consideration. It is considered that for brakes a very small length change in housings is less important than it would be for gear shifting, though with the advent of v-brake 1mm block clearances the issue is by no means resolved. It may have been noted by some that when a bike is not being ridden, an excessive twist of the handlebars or the bending caused by folding a bike can cause a rear brake to operate. However, it is unlikely that such bending could happen while actually riding the bike, provided that the housings were made specifically for brakes, and are of good quality.

- For Gear Shifting: The preferred product for gear-shifting uses longitudinal reinforcement, and is stated as being compressionless. These housings suffer virtually no length changes when the cables are moved or subjected to end pressure, and as such are ideally suited to cog sets with a narrow pitch. For example, Shimano gear trains use as little as 2.3mm of cable pull to change gear with its 10-speed cog-sets, so a fairly small length change in a housing might become significant. Housing with longitudinally arranged reinforcement, is not as strong as the housing with spiral steel so should not be used for brakes. Use only good quality housings that are made for the specific purpose.

- Sizes: Cable housings for bicycles exist in both 4mm and 5mm diameters, and their ferrules and other tight fittings must be selected to match. Although in the past these housings have been manufactured only with black coatings, they are generally available in a dozen or so colors to match bike color schemes in both diameters. The most commonly used size for brakes is of 5mm diameter, and for shifting is 4mm, but exceptions commonly exist and both sizes are to be found for each purpose. Check the sizes of the old housings and ferrules before any new purchase, to make sure that the new ones will still loose-fit the barrel-adjusters.

Ferrules and Fittings

- Ferrules: These are end-caps that fit onto both ends of the housing. They prevent the fraying of the housing ends and present a durable surface to press against barrel adjusters or fittings on the frame. They also act as cable guides to ensure that the cable is aligned with the housings' sleeves. They are often made of plastic, but sometimes are made of metal. In general, the plastic items are the most common and are made to be a tight fit on the housing, while metal ferrules are often crimped to secure them. Ferrules are made for a particular diameter of housing. Some ferrules are made to fit into the frame's cable stops, though these might not be the correct diameter for the end of the barrel adjuster. In particular, the fittings found on some universal products (housing, cable, and fittings complete ), while fitting points on the frame, might need special care to make sure that they are a loose fit in the barrel.

- Noodles/Transitions: Brakes arms are connected to the cable housing at the cable bridge, where a nipple on a noodle locks onto it. This fitting has a sweeping curve that allows the incoming cable direction to be changed without kinking the cable or its housing. It is either a solid noodle or is sprung. Cable housings are tightly pressed into these noodles so must be selected with the correct diameter. They are often supplied at purchase with a rubber boot, a flexible rubber piece to protect the exposed cable at the brake arm assembly.

- Barrel-adjusters: These fittings are most often sold as a part of a brake lever, a gear shifter, or a derailleur, but they are sometimes supplied as accessories for the middle of a cable run. The adjusters on handlebars can be adjusted while pedalling so are more convenient than those installed elsewhere on the bike. In any case, all barrel-adjusters must be able to loose-fit a housing ferrule in their ends, and since housings and ferrules exist in both 4 and 5 mm sizes, it is important to make sure that any ferrule used will not bind there.

- Cable stops on frames: Many bicycle frames have points on them to receive housing ferrules; these are referred to as cable stops. Whether or not there is a standard size for these openings is at present unclear, and in any case the main point is that they fit at all. (But see comments above for ferrules in barrel adjuster openings.)

A brake barrel adjuster. The large ring is a lock for the smaller one, the adjuster. Notice the crimped ferrule where the housing makes a loose entry. | This kind of adjuster is found on some rear derailleurs. It can exist in addition to one on the shifter. | A cable stop welded to the frame. A silver housing with a ferrule fits at the bottom and the internal steel cable continues at the top. |  Note the black barrel adjuster on the gear shifter and the silver one on the brake lever. |

A typical plastic barrel-adjuster. The housing normally would abut within the adjuster-cap while the cable continues onward. | This type of cable cap is crimped onto cable ends, like the ones on the brake and derailleur. |

Installing Housings

Minor Repairs

It is rare for complete housings to need replaced, and most of the time it is a matter of trimming a bad housing end at the barrel-adjuster, replacing ferrules, or tidying up a messy cable end. Provided that the handlebar loop in the housing is fairly generous, and in particular, provided that about ten or twelve centimeters (about 4 inches or so) could be removed from it there without any problem, then the existing housing might be reused for all three of these situations. The basis for this comment is as follows:

- In order to trim the housing's end, and perhaps fit a new ferrule at the adjuster on the handlebars, the cable must be removed from the housing, and reinserted after the changes.

- When the cable is removed from its brake or derailleur clamp the part that is flattened by the clamp will not feed through the housing, and so the flattened end of the cable must be removed.

- Now, in order to find enough spare cable for re-clamping, an additional ten or twelve centimeters (about 4 inches) of housing at the handlebars will need to be removed during the trimming process.

- Thus, provided that there is enough spare housing at the handlbars, all will be well. A short consideration will show that an identical situation exists whenever a flattened cable tail needs to be removed.

Housing Length

Occasionally cable housings are completely replaced, for example, in favor of the new colored housing varieties, or when the wrong thing was installed in the first place. It might also happen that numerous changes have left the housings a bit short. In any case, when replacing housings be sure to consider the following points:

- If replacing housings entirely, it is best to replace the cables at the same time. This will allow you to install the spare capacity that is needed for any future repairs. (See above).

- The most important consideration for the quality of installation lies in ensuring that they are installed with only smooth curves, and have no sudden direction changes. No figures have been found for the required minimum radii of curvature in housings, so the matter is largely based on what works well. The matter of minimum length is easier to establish. The worst situation for handlebar restriction on cables is when the handlebars are turned in either direction to their fullest extent. Generally speaking this will meet the minimum requirement, provided that the cable bends are not too sharp. In addition to this, consider the possible future need to rework the housings, so add at least an extra ten or twelve centimeters (4 inches or so) of housing to the minimum length. Finally, consider whether or not the planned length is how you intend it to look from any other points of view, and possibly add more, but not less to the total. The consequence of excessively long cables is snagging, but this is mostly of concern for downhill riding or perhaps road racing.

- If the existing housing lengths were satisfactory, then just make the new ones the same length.

Cutting

The only reliable way to cut housings and cables is with a special cable cutter made for the purpose; these are available from most bike shops and by internet purchase. A Dremel tool with a cutting disk will work great, also. Pliers, side cutters, hacksaws, all will make a mess of it. A housing cutter has a v-shape in each blade that avoids collapsing the end while it is cut, and even then the end of cut housings need cleared so that the cable can fit into the inner sleeve. Some housing kits are supplied for particular bikes, cut to length, and with the ferrules pre-fitted, but the material that follows assumes that they must be constructed. A housing cutter can also be used to cut the inner cable, but before doing any stripping of the old work or cutting, it is as well to also be aware of these points:

- Do not remove the welded end from a new inner cable until the very last thing in the fitting process. This will avoid any cable fraying.

- If working with some shifters such as SRAM GripShifts, do not remove the cable from the shifter unless it is necessary, since it takes a little effort to replace. Other shifter cables can be easier to fit, and brake cable ends are always fairly easy.

- Remove any cable from the housing to be cut, and make a square cut at the chosen point. If the cut is bad, or the end badly mangled make another a few millimeters from it. Clear the cable sleeve with a small object; the smallest hex wrench has been found useful, as has the passing of a piece of old cable through the housing from the other end to clear it . A cocktail stick or toothpick might be useful for this also. In any case, for success the cable must be able to pass freely into the entire length of the housing's cable sleeve with the ferrules fitted.

- First check that the ferrules loose-fit their intended insertion points then fit them onto the housings.

- Cutting all of the housings to length and fitting their ferrules before running the cable is the best check of the ferrule's alignment, and prevents missing out a ferrule during the wiring, but the cable could be run through the ferrules and housings separately, and these items connected afterwards if this proves more convenient.

Assembly

Because each change to installed cabling and housing causes the loss of cable length, it is best if assembly and final clamping of cable is put off until all changes are complete. The general procedure, starting at the handlebars, is as follows:

- Fix the cable terminal: Insert the cable terminals, the barrel, pear-end, or button into the brake lever or shifter in accordance with the instructions for the equipment. For brakes this usually means lining up the slots in the barrel adjusters so that the terminals can be anchored in the underside of the levers. Some shifters use a similar method but others are pre-wired, (eg: SRAM GripShift 7-speed Comp); in these latter cases be careful not remove the cable from the shifter.

- Add the first housing: With the cable anchored, thread the intact welded end of the cable through the ferrule-fitted housing, and take up the slack cable so that the housing's ferrule is sitting freely inside the end of the barrel adjuster. Dress the housing loop at the handlebars and press the housing into any guides on the frame, being careful to maintain gradual sweeps in any transitions. If the cable run uses a cable stop in the frame for the first housing section then press the ferrule into it. Repeat for any other sections of housing in the cable run, (you may leave a straight middle section bare if necessary). Take up the slack.

- Dress the cable end: Dress the last housing's end into any cable stops and fit any end parts that are needed.

- In the case of brakes: After attaching the piece with the end nipple, fix its nipple into the slot on the brake's cable bridge, and loose-wire the cable past the cable clamp. Take up the slack, check the cable remains in place and that the ferrules are still seated.

- In the case of derailleurs: Thread the cable end around the derailleur in accordance with the manufacturer's details and loose-wire the cable past the cable clamp. Derailleurs usually have a groove or channel for the cable route at the derailleur. Note that the way that the cable is finally clamped (e.g. near side, far side, top or bottom), can affect the leverage of shifting and in all cases the installation instructions for the derailleur should be followed. Take up the slack, check the cable remains in place and that the ferrules are still seated.

- Attach the cable ends: Only when it is certain that the work is complete should the cables be attached. Follow the instructions for brake or derailleur adjustment in attaching the inner cables. (See the links below).

- Cut the cable end: Only after the brakes or derailleur is both adjusted and tested should the cable be cut. Allow at least 10cms (about 4 inches) of cable tail beyond the clamp, and after cutting, crimp a cable cap onto the cable to prevent fraying, and make sure that the tail is clear of moving parts.