Vertebrobasilar insufficiency

Background

- Characterized by diminished blood flow through the vertebral or basilar arteries

- The two vertebral arteries originally branch proximally from subclavian, travel through vertebrae, and distally join to become basilar artery

- Symptoms result from diminished circulation to the posterior brain, brainstem and cerebellum.

- Head-turning can cause ipsilateral vertebral artery to temporarily occlude

- Head extension may also provoke symptoms

- Neurologic symptoms tend to not present when one vertebral artery remains patent[2]

- Symptoms may result secondary to arterial plaques, arterial dissection, compressive lesions, or subclavian steal (see below). *Posterior strokes encompass 20-30% of all strokes[3]

- Cervical osteophytes can also directly compress vertebral arteries and cause VBI symptoms[4].

Bow hunter's syndrome (Rotational vertebral artery compression)

Subclavian steal phenomenon

- Stenotic lesion in the subclavian, located proximal to the vertebral artery--> reversed flow of blood in the vertebral artery when superimposed with increased arm activity(4).

Clinical Features

Symptoms

- Numbness/tingling

- Vertigo/dizziness

- Changes in vision

- Nausea/vomiting

- Weakness

- Dysphagia

- Dysarthria

- Syncope

Differential Diagnosis

Vertigo

- Vestibular/otologic

- Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV)

- Traumatic (following head injury)

- Infection

- Meniere's disease

- Ear foreign body

- Otic barotrauma

- Neurologic

- Cerebellar stroke

- Vertebrobasilar insufficiency

- Lateral Wallenberg syndrome

- Anterior inferior cerebellar artery syndrome

- Neoplastic: cerebellopontine angle tumors

- Basal ganglion diseases

- Vertebral Artery Dissection

- Multiple sclerosis

- Infections: neurosyphilis, tuberculosis

- Epilepsy

- Migraine (basilar)

- Other

- Hematologic: anemia, polycythemia, hyperviscosity syndrome

- Toxic

- Chronic renal failure

- Metabolic

Evaluation

Work-up

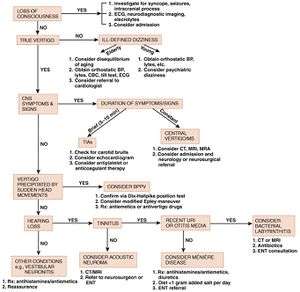

Diagnostic algorithm Vertigo

- Glucose check

- Full neuro exam

- TM exam

- CTA or MRA (diagnostic study of choice) of the neck/brain if symptoms consistent with central cause

| Test | Sensitivity |

| HINTS | 100% |

| MRI (24hrs) | 68.40%[7] |

| MRI (48hrs) | 81%[7] |

| CT non con | 26%[8] |

Inclusion Criteria

- HINTS exam should only be used in patient with acute persistent vertigo, nystagmus, and a normal neurological exam.

The 3 components of the HINTS exam include:

| HINTS Test | Reassuring Finding |

| Head Impulse Test | Abnormal (corrective saccade) |

| Nystagmus | Unidirectional, horizontal |

| Test of Skew | No skew deviation |

Head Impulse Test

Test of vestibulo-ocular reflex function

- Have patient fix their eyes on your nose

- Move their head in the horizontal plane to the left and right

- When the head is turned towards the normal side, the vestibular ocular reflex remains intact and eyes continue to fixate on the visual target

- When the head is turned towards the affected side, the vestibular ocular reflex fails and the eyes make a corrective saccade to re-fixate on the visual target [12][13]

- Normally, a functional vestibular system will identify any movement of the head position and rapidly correct eye movement accordingly so that the center of the vision remains on a target.

- This reflex fails in peripheral causes of vertigo effective the vestibulocochlear nerve

- It is reassuring if the reflex is abnormal (due to dysfunction of the peripheral nerve)

Nystagmus

- Observation for nystagmus in primary, right, and left gaze

- No nystagmus (normal) or only horizontal unilateral nystagmus is reassuring

- Any other type of nystagmus is abnormal, including bidirectional nystagmus

Test of Skew

- Have patient look at your nose with their eyes and then cover one eye

- Then rapidly uncover the eye and quickly look to see if the eye moves to re-align.

- Repeat with on each eye

- Skew deviation is a fairly specific predictor of brainstem involvement in patients with acute vestibular syndrome. The presence of skew may help identify stroke when a positive head impulse test falsely suggests a peripheral lesion.

- Skew is also known vertical dysconjugate gaze and is a sign of a central lesion

- A positive HINTS exam: 100% sensitive and 96% specific for the presence of a central lesion.

- The HINTS exam was more sensitive than general neurological signs: 100% versus 51%.

- The sensitivity of early MRI with DWI for lateral medullary or pontine stroke was lower than that of the HINTS examination (72% versus 100%, P=0.004) with comparable specificity (100% versus 96%, P=1.0).

- If any of the above 3 tests are consistent with CVA obtain full work-up (including MRI)

Management

Medical management

- Lower cholesterol

- Control hypertension

- Smoking cessation

- Antiplatelets

Surgical management

- Endarterectomy

- Bypass grafting

- Stenting

Disposition

- Admit

See Also

External Links

References

-

- Go G, Hwang S-H, Park IS, Park H. Rotational Vertebral Artery Compression : Bow Hunter’s Syndrome. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society. 2013;54(3):243-245. doi:10.3340/jkns.2013.54.3.243.

- Ibrahim Alnaami, Muzaffer Siddiqui, and Maher Saqqur, “The Diagnosis of Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency Using Transcranial Doppler Ultrasound,” Case Reports in Medicine, vol. 2012, Article ID 894913, 3 pages, 2012. doi:10.1155/2012/894913.

- Ibrahim Alnaami, Muzaffer Siddiqui, and Maher Saqqur, “The Diagnosis of Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency Using Transcranial Doppler Ultrasound,” Case Reports in Medicine, vol. 2012, Article ID 894913, 3 pages, 2012. doi:10.1155/2012/894913.

- Tintinalli

-

- Go G, Hwang S-H, Park IS, Park H. Rotational Vertebral Artery Compression : Bow Hunter’s Syndrome. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society. 2013;54(3):243-245. doi:10.3340/jkns.2013.54.3.243.

-

- Go G, Hwang S-H, Park IS, Park H. Rotational Vertebral Artery Compression : Bow Hunter’s Syndrome. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society. 2013;54(3):243-245. doi:10.3340/jkns.2013.54.3.243.

- http://www.cnsuwo.ca/ebn/downloads/cats/2010/CNS-EBN_cat-document_2010-07-JUL-30_a-negative-dwi-mri-within-48-hours-of-stroke-symptoms-ruled-out-anterior-circulation-stroke_4494E.pdf

- Chalela JA, Kidwell CS, Nentwich LM, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in emergency assessment of patients with suspected acute stroke: a prospective comparison. Lancet. 2007;369:293–8.

- http://ec.libsyn.com/p/a/d/d/add761f2a2847ea5/hints-exam.pdf?d13a76d516d9dec20c3d276ce028ed5089ab1ce3dae902ea1d01c0873ed8cc5fe910&c_id=2502227

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18541870

- http://hwcdn.libsyn.com/p/1/c/d/1cd6b38a89c178a1/diff-of-vertigo.pdf?c_id=2502226&expiration=1380995436&hwt=0a8bc67ea910e018a1543ebea192f668

- Barraclough K, Bronstein A. Vertigo. BMJ. 2009;339:b3493

- Kuo CH, Pang L, Chang R. Vertigo - part 1 - assessment in general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2008;37(5):341-7

This article is issued from

Wikem.

The text is licensed under Creative

Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.