Skull fracture (peds)

This page is for pediatric patients; for adult patients see skull fracture

Background

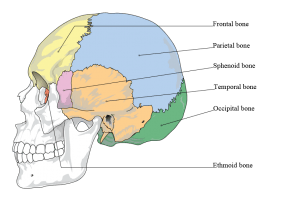

Bones of the cranium.

- Predictor of intracranial injury

- Infants are at higher risk due to thinner calvarium (median age for isolated skull fracture is 10 months)[1]

- Most skull fractures have overlying hematoma

Clinical Features

- Scalp hematoma

- Skull tenderness

- Skull depression or crepitus

- Battle sign or raccoon eyes (basilar skull fracture)

- Loss of consciousness, nausea/vomiting, altered mental status (less common in younger children than other children and adults with isolated skull fracture)[1]

Differential Diagnosis

Head trauma

- Traumatic brain injury

- Orbital trauma

- Maxillofacial trauma

- Skull fracture

- Pediatric head trauma

Evaluation

- Head CT

- Evaluate for additional injuries

Management

- Consider antibiotics for:

- Open fracture

- Depressed fracture

- Sinus involvement

- Pneumocephalus

- Ceftriaxone AND metronidazole +/- vancomycin

Disposition

- Consider discharge if[2][1]:

- Neurologically normal

- Isolated closed linear skull fracture

- No concern for non-accidental trauma

- Admit all others

See Also

- Head Trauma

- Skull fracture (Adult)

External Links

References

- Elizabeth C. Powell, et al. Isolated Linear Skull Fractures in Children With Blunt Head Trauma. Pediatrics Apr 2015, 135 (4) e851-e857; DOI: 10.1542/peds.2014-2858

- Bressan, S., Marchetto, L., Lyons, T. W., Monuteaux, M. C., Freedman, S. B., Da Dalt, L., & Nigrovic, L. E. (2018). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Management and Outcomes of Isolated Skull Fractures in Children. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 71(6), 714–724.e2.

This article is issued from

Wikem.

The text is licensed under Creative

Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.