IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, Working Group III: Chapter 8

Originally published by our Content Partner: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (other articles)

Agriculture

This chapter should be cited as:

Smith, P., D. Martino, Z. Cai, D. Gwary, H. Janzen, P. Kumar, B. McCarl, S. Ogle, F. O’Mara, C. Rice, B. Scholes, O. Sirotenko, 2007: Agriculture. In Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Metz, O.R. Davidson, P.R. Bosch, R. Dave, L.A. Meyer (eds), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

Executive Summary

Agricultural lands (lands used for agricultural production, consisting of cropland, managed grassland and permanent crops including agro-forestry and bio-energy crops) occupy about 40-50% of the Earth’s land surface.

Agriculture accounted for an estimated emission of 5.1 to 6.1 GtCO2-eq/yr in 2005 (10-12% of total global anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs)). CH4 contributes 3.3 GtCO2-eq/yr and N2O 2.8 GtCO2-eq/yr. Of global anthropogenic emissions in 2005, agriculture accounts for about 60% of N2O and about 50% of CH4 (medium agreement, medium evidence). Despite large annual exchanges of CO2 between the atmosphere and agricultural lands, the net flux is estimated to be approximately balanced, with CO2 emissions around 0.04 GtCO2/yr only (emissions from electricity and fuel use are covered in the buildings and transport sector, respectively) (low agreement, limited evidence).

Globally, agricultural CH4 and N2O emissions have increased by nearly 17% from 1990 to 2005, an average annual emission increase of about 60 MtCO2-eq/yr. During that period, the five regions composed of Non-Annex I countries showed a 32% increase, and were, by 2005, responsible for about three- quarters of total agricultural emissions. The other five regions, mostly Annex I countries, collectively showed a decrease of 12% in the emissions of these gases (high agreement, much evidence).

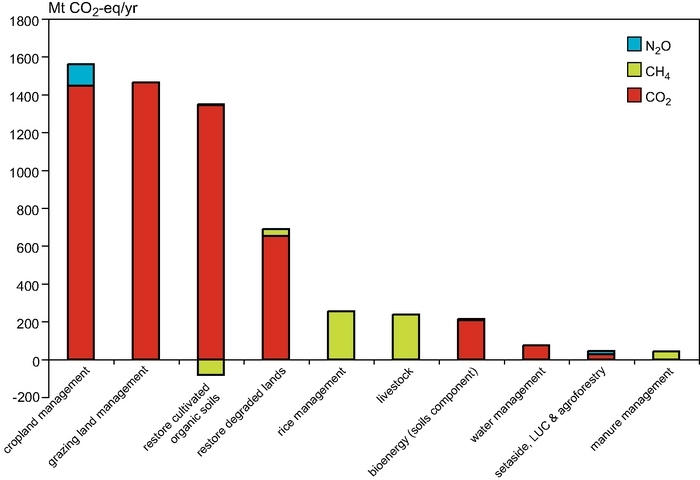

A variety of options exists for mitigation of GHG emissions in agriculture. The most prominent options are improved crop and grazing land management (e.g., improved agronomic practices, nutrient use, tillage, and residue management), restoration of organic soils that are drained for crop production and restoration of degraded lands. Lower but still significant mitigation is possible with improved water and rice management; set-asides, land use change (e.g., conversion of cropland to grassland) and agro-forestry; as well as improved livestock and manure management. Many mitigation opportunities use current technologies and can be implemented immediately, but technological development will be a key driver ensuring the efficacy of additional mitigation measures in the future (high agreement, much evidence).

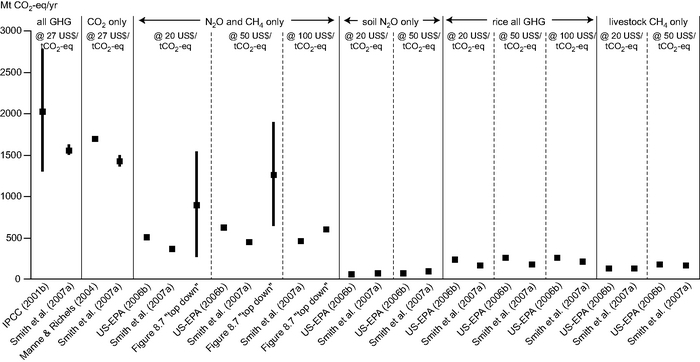

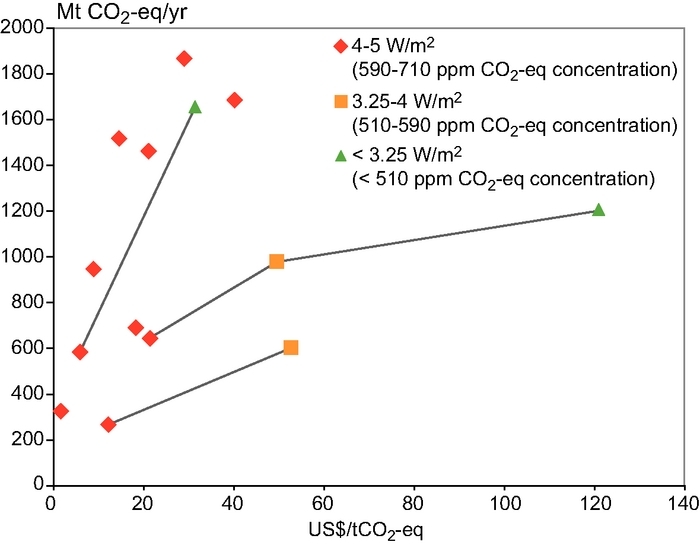

Agricultural GHG mitigation options are found to be cost competitive with non-agricultural options (e.g., energy, transportation, forestry) in achieving long-term (i.e., 2100) climate objectives. Global long-term modelling suggests that non-CO2 crop and livestock abatement options could cost-effectively contribute 270–1520 MtCO2-eq/yr globally in 2030 with carbon prices up to 20 US$/tCO2-eq and 640–1870 MtCO2-eq/yr with C prices up to 50 US$/tCO2-eq Soil carbon management options are not currently considered in long-term modelling (medium agreement, limited evidence).

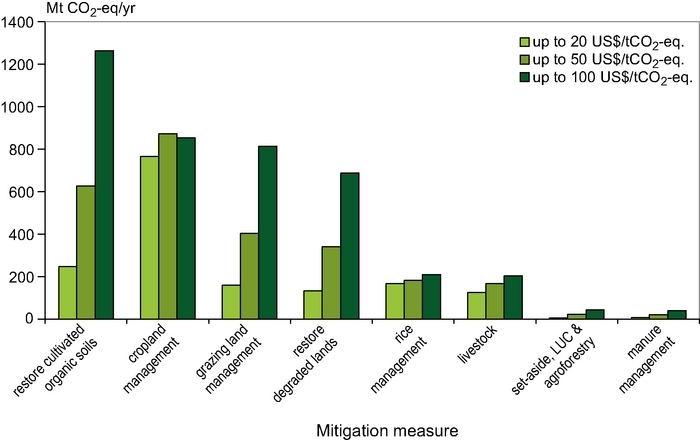

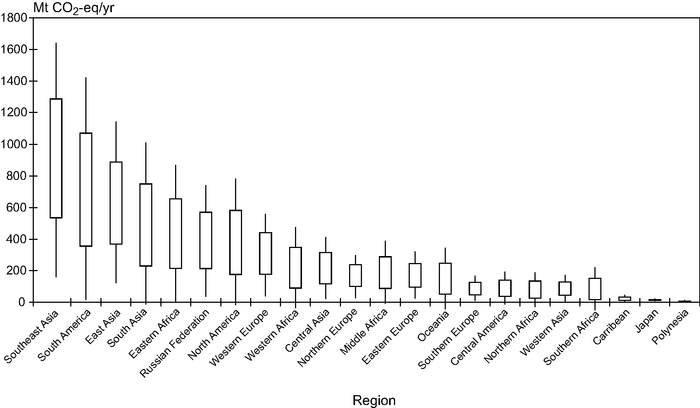

Considering all gases, the global technical mitigation potential from agriculture (excluding fossil fuel offsets from biomass) by 2030 is estimated to be ~5500-6,000 MtCO2-eq/yr (medium agreement, medium evidence). Economic potentials are estimated to be 1500-1600, 2500-2700, and 4000-4300 MtCO2-eq/yr at carbon prices of up to 20, 50 and 100 US$/ tCO2-eq, respectively About 70% of the potential lies in non-OECD/EIT countries, 20% in OECD countries and 10% for EIT countries (medium agreement, limited evidence).

Soil carbon sequestration (enhanced sinks) is the mechanism responsible for most of the mitigation potential (high agreement, much evidence), with an estimated 89% contribution to the technical potantial. Mitigation of CH4 emissions and N2O emissions from soils account for 9% and 2%, respectively, of the total mitigation potential (medium agreement, medium evidence). The upper and lower limits about the estimates are largely determined by uncertainty in the per-area estimate for each mitigation measure. Overall, principal sources of uncertainties inherent in these mitigation potentials include: a) future level of adoption of mitigation measures (as influenced by barriers to adoption); b) effectiveness of adopted measures in enhancing carbon sinks or reducing N2O and CH4 emissions (particularly in tropical areas; reflected in the upper and lower bounds given above); and c) persistence of mitigation, as influenced by future climatic trends, economic conditions, and social behaviour (medium agreement, limited evidence).

The role of alternative strategies changes across the range of prices for carbon. At low prices, dominant strategies are those consistent with existing production such as changes in tillage, fertilizer application, livestock diet formulation, and manure management. Higher prices elicit land-use changes that displace existing production, such as biofuels, and allow for use of costly animal feed-based mitigation options. A practice effective in reducing emissions at one site may be less effective or even counterproductive elsewhere. Consequently, there is no universally applicable list of mitigation practices; practices need to be evaluated for individual agricultural systems based on climate, edaphic, social setting, and historical patterns of land use and management (high agreement, much evidence).

GHG emissions could also be reduced by substituting fossil fuels with energy produced from agricultural feed stocks (e.g., crop residues, dung, energy crops), which would be counted in sectors using the energy. The contribution of agriculture to the mitigation potential by using bioenergy depends on relative prices of the fuels and the balance of supply and demand. Using top-down models that include assumptions on such a balance the economic mitigation potential for agriculture in 2030 is estimated to be 70-1260 MtCO2-eq/yr at up to 20 US$/tCO2-eq, and 560-2320 MtCO2-eq/yr at up to 50 US$/tCO2-eq There are no estimates for the additional potential from top down models at carbon prices up to 100 US$/tCO2-eq, but the estimate for prices above 100 US$/tCO2-eq is 2720 MtCO2-eq/yr. These potentials represent mitigation of 5-80%, and 20-90% of all other agricultural mitigation measures combined, at carbon prices of up to 20, and up to50 US$/tCO2-eq, respectively. An additional mitigation of 770 MtCO2-eq/yr could be achieved by 2030 by improved energy efficiency in agriculture, though the mitigation potential is counted mainly in the buildings and transport sectors (medium agreement, medium evidence).

Agricultural mitigation measures often have synergy with sustainable development policies, and many explicitly influence social, economic, and environmental aspects of sustainability. Many options also have co-benefits (improved efficiency, reduced cost, environmental co-benefits) as well as trade-offs (e.g., increasing other forms of pollution), and balancing these effects will be necessary for successful implementation (high agreement, much evidence).

There are interactions between mitigation and adaptation in the agricultural sector, which may occur simultaneously, but differ in their spatial and geographic characteristics. The main climate change benefits of mitigation actions will emerge over decades, but there may also be short-term benefits if the drivers achieve other policy objectives. Conversely, actions to enhance adaptation to climate change impacts will have consequences in the short and long term. Most mitigation measures are likely robust to future climate change (e.g., nutrient management), but a subset will likely be vulnerable (e.g., irrigation in regions becoming more arid). It may be possible for a vulnerable practice to be modified as the climate changes and to maintain the efficacy of a mitigation measure (low agreement, limited evidence).

In many regions, non-climate policies related to macro- economics, agriculture and the environment, have a larger impact on agricultural mitigation than climate policies (high agreement, much evidence). Despite significant technical potential for mitigation in agriculture, there is evidence that little progress has been made in the implementation of mitigation measures at the global scale. Barriers to implementation are not likely to be overcome without policy/economic incentives and other programmes, such as those promoting global sharing of innovative technologies.

Current GHG emission rates may escalate in the future due to population growth and changing diets (high agreement, medium evidence). Greater demand for food could result in higher emissions of CH4 and N2O if there are more livestock and greater use of nitrogen fertilizers (high agreement, much evidence). Deployment of new mitigation practices for livestock systems and fertilizer applications will be essential to prevent an increase in emissions from agriculture after 2030. In addition, soil carbon may be more vulnerable to loss with climate change and other pressures, though increases in production will offset some or all of this carbon loss (low agreement, limited evidence).

Overall, the outlook for GHG mitigation in agriculture suggests that there is significant potential (high agreement, medium evidence). Current initiatives suggest that synergy between climate change policies, sustainable development and improvement of environmental quality will likely lead the way forward to realize the mitigation potential in this sector.

8.1 Introduction

Agriculture releases to the atmosphere significant amounts of CO2, CH4, and N2O (Cole et al., 1997; IPCC, 2001a; Paustian et al., 2004). CO2 is released largely from microbial decay or burning of plant litter and soil organic matter (Smith, 2004b; Janzen, 2004). CH4 is produced when organic materials decompose in oxygen-deprived conditions, notably from fermentative digestion by ruminant livestock, from stored manures, and from rice grown under flooded conditions (Mosier et al. 1998). N2O is generated by the microbial transformation of nitrogen in soils and manures, and is often enhanced where available nitrogen (N) exceeds plant requirements, especially under wet conditions (Oenema et al., 2005; Smith and Conen, 2004). Agricultural greenhouse gas (GHG) fluxes are complex and heterogeneous, but the active management of agricultural systems offers possibilities for mitigation. Many of these mitigation opportunities use current technologies and can be implemented immediately.

This chapter describes the development of GHG emissions from the agricultural sector (Section 8.2), and details agricultural practices that may mitigate GHGs (Section 8.4.1), with many practices affecting more than one GHG by more than one mechanism. These practices include: cropland management; grazing land management/pasture improvement; management of agricultural organic soils; restoration of degraded lands; livestock management; manure/bio-solid management; and bio-energy production.

It is theoretically possible to increase carbon storage in long-lived agricultural products (e.g., strawboards, wool, leather, bio-plastics) but the carbon held in these products has only increased from 37 to 83 MtC per year over the past 40 years. Assuming a first order decay rate of 10 to 20% per year, this is estimated to be a global net annual removal of 3 to 7 MtCO2 from the atmosphere, which is negligible compared to other mitigation measures. The option is not considered further here.

Smith et al. (2007a) recently estimated a global potential mitigation of 770 MtCO2-eq/yr by 2030 from improved energy efficiency in agriculture (e.g., through reduced fossil fuel use), However, this is usually counted in the relevant user sector rather than in agriculture and so is not considered further here. Any savings from improved energy efficiency are discussed in the relevant sections elsewhere in this volume, according to where fossil fuel savings are made, for example, from transport fuels (Chapter 5), or through improved building design (Chapter 6).

8.2 Status of sector, development trends including production and consumption, and implications

Population pressure, technological change, public policies, and economic growth and the cost/price squeeze have been the main drivers of change in the agricultural sector during the last four decades. Production of food and fibre has more than kept pace with the sharp increase in demand in a more populated world. The global average daily availability of calories per capita has increased (Gilland, 2002), with some notable regional exceptions. This growth, however, has been at the expense of increased pressure on the environment, and depletion of natural resources (Tilman et al., 2001; Rees, 2003), while it has not resolved the problems of food security and child malnutrition suffered in poor countries (Conway and Toenniessen, 1999).

Agricultural land occupied 5023 Mha in 2002 (FAOSTAT, 2006). Most of this area was under pasture (3488 Mha, or 69%) and cropland occupied 1405 Mha (28%). During the last four decades, agricultural land gained almost 500 Mha from other land uses, a change driven largely by increasing demands for food from a growing population. Every year during this period, an average 6 Mha of forestland and 7 Mha of other land were converted to agriculture, a change occurring largely in the developing world (Table 8.1). This trend is projected to continue into the future (Huang et al., 2002; Trewavas, 2002; Fedoroff and Cohen, 1999; Green et al., 2005), and Rosegrant et al., (2001) project that an additional 500 Mha will be converted to agriculture during 1997-2020, mostly in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Table 8.1. Agricultural land use in the last four decades.

| Area (Mha) | Change 2000s/1960s | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1961-70 | 1971-80 | 1981-90 | 1991-00 | 2001-02 | % | Mha | |

| 1. World | |||||||

| Agricultural land | 4,562 | 4,684 | 4,832 | 4,985 | 5,023 | +10 | 461 |

| Arable land | 1,297 | 1,331 | 1,376 | 1,393 | 1,405 | +8 | 107 |

| Permanent crops | 82 | 92 | 104 | 123 | 130 | +59 | 49 |

| Permanent pasture | 3,182 | 3,261 | 3,353 | 3,469 | 3,488 | +10 | 306 |

| 2. Developed countries | |||||||

| Agricultural land | 1,879 | 1,883 | 1,877 | 1,866 | 1,838 | -2 | -41 |

| Arable land | 648 | 649 | 652 | 633 | 613 | -5 | -35 |

| Permanent crops | 23 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | +4 | 1 |

| Permanent pasture | 1,209 | 1,210 | 1,201 | 1,209 | 1,202 | -1 | -7 |

| 3. Developing countries | |||||||

| Agricultural land | 2,682 | 2,801 | 2,955 | 3,119 | 3,184 | +19 | 502 |

| Arable land | 650 | 682 | 724 | 760 | 792 | +22 | 142 |

| Permanent crops | 59 | 68 | 80 | 99 | 106 | +81 | 48 |

| Permanent pasture | 1,973 | 2,051 | 2,152 | 2,260 | 2,286 | +16 | 313 |

Source: FAOSTAT, 2006.

Technological progress has made it possible to achieve remarkable improvements in land productivity, increasing per- capita food availability (Table 8.2), despite a consistent decline in per-capita agricultural land (Figure 8.1). The share of animal products in the diet has increased consistently in the developing countries, while remaining constant in developed countries (Table 8.2). Economic growth and changing lifestyles in some developing countries are causing a growing demand for meat and dairy products, notably in Chinawhere current demands are low. Meat demand in developing countries rose from 11 to 24 kg/capita/yr during the period 1967-1997, achieving an annual growth rate of more than 5% by the end of that period. Rosegrant et al. (2001) forecast a further increase of 57% in global meat demand by 2020, mostly in South and Southeast Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. The greatest increases in demand are expected for poultry (83% by 2020; Roy et al., 2002).

Table 8.2: Per capita food supply in developed and developing countries

| Change 2000s/1960s | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1961-70 | 1971-80 | 1981-90 | 1991-00 | 2001-02 | % | cal/d or g/d | |

| 1. Developed countries | |||||||

| Energy, all sources (cal/day) | 3049 | 3181 | 3269 | 3223 | 3309 | +9 | 261 |

| % from animal sources | 27 | 28 | 28 | 27 | 26 | -2 | -- |

| Protein, all sources (g/day) | 92 | 97 | 101 | 99 | 100 | +9 | 8 |

| % from animal sources | 50 | 55 | 57 | 56 | 56 | +12 | -- |

| 2. Developing countries | |||||||

| Energy, all sources (cal/day) | 2032 | 2183 | 2443 | 2600 | 2657 | +31 | 625 |

| % from animal sources | 8 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 13 | +77 | -- |

| Protein, all sources (g/day) | 9 | 11 | 13 | 18 | 21 | +123 | 48 |

| % from animal sources | 18 | 20 | 22 | 28 | 30 | +67 | -- |

| Source: FAOSTAT, 2006. | |||||||

Annual GHG emissions from agriculture are expected to increase in coming decades (included in the baseline) due to escalating demands for food and shifts in diet. However, improved management practices and emerging technologies may permit a reduction in emissions per unit of food (or of protein) produced. The main trends in the agricultural sector with the implications for GHG emissions or removals are summarized as follows:

- Growth in land productivity is expected to continue, although at a declining rate, due to decreasing returns from further technological progress, and greater use of marginal land with lower productivity. Use of these marginal lands increases the risk of soil erosion and degradation, with highly uncertain consequences for CO2 emissions (Lal, 2004a; Van Oost et al., 2004).

- Conservation tillage and zero-tillage are increasingly being adopted, thus reducing the use of energy and often increasing carbon storage in soils. According to FAO (2001), the worldwide area under zero-tillage in 1999 was approximately 50 Mha, representing 3.5% of total arable land. However, such practices are frequently combined with periodical tillage, thus making the assessment of the GHG balance highly uncertain.

- Further improvements in productivity will require higher use of irrigation and fertilizer, increasing the energy demand (for moving water and manufacturing fertilizer; Schlesinger, 1999). Also, irrigation and N fertilization can increase GHG emissions (Mosier, 2001).

- Growing demand for meat may induce further changes in land use (e.g., from forestland to grassland), often increasing CO2 emissions, and increased demand for animal feeds (e.g., cereals). Larger herds of beef cattle will cause increased emissions of CH4 and N2O, although use of intensive systems (with lower emissions per unit product) is expected to increase faster than growth in grazing-based systems. This may attenuate the expected rise in GHG emissions.

- Intensive production of beef, poultry, and pork is increasingly common, leading to increases in manure with con- sequent increases in GHG emissions. This is particularly true in the developing regions of South and East Asia, and Latin America, as well as in North America.

- Changes in policies (e.g., subsidies), and regional patterns of production and demand are causing an increase in inter- national trade of agricultural products. This is expected to increase CO2 emissions, due to greater use of energy for transportation.

- There is an emerging trend for greater use of agricultural products (e.g., bio-plastics bio-fuels and biomass for energy) as substitutes for fossil fuel-based products. This has the potential to reduce GHG emissions in the future.

8.3 Emission trends (global and regional)

With an estimated global emission of non-CO2 GHGs from agriculture of between 5120 MtCO2-eq/yr (Denman et al., 2007) and 6116 MtCO2-eq/yr (US-EPA, 2006a) in 2005, agriculture accounts for 10-12% of total global anthropogenic emissions of GHGs. Agriculture contributes about 47% and 58% of total anthropogenic emissions of CH4 and N2O, respectively, with a wide range of uncertainty in the estimates of both the agricultural contribution and the anthropogenic total. N2O emissions from soils and CH4 from enteric fermentation constitute the largest sources, 38% and 32% of total non-CO2 emissions from agriculture in 2005, respectively (US-EPA, 2006a). Biomass burning (12%), rice production (11%), and manure management (7%) account for the rest. CO2 emissions from agricultural soils are not normally estimated separately, but are included in the land use, land use change and forestry sector (e.g., in national GHG inventories). So there are few comparable estimates of emissions of this gas in agriculture. Agricultural lands generate very large CO2 fluxes both to and from the atmosphere (IPCC, 2001a), but the net flux is small. US-EPA, 2006b) estimated a net CO2 emission of 40 MtCO2-eq from agricultural soils in 2000, less than 1% of global anthropogenic CO2 emissions.

Both the magnitude of the emissions and the relative importance of the different sources vary widely among world regions (Figure 8.2). In 2005, the group of five regions mostly consisting of non-Annex I countries was responsible for 74% of total agricultural emissions.

In seven of the ten regions, N2O from soils was the main source of GHGs in the agricultural sector in 2005, mainly associated with N fertilizers and manure applied to soils. In the other three regions - Latin America and The Caribbean, the countries of Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia, and OECD Pacific - CH4 from enteric fermentation was the dominant source (US-EPA, 2006a). This is due to the large livestock population in these three regions which, in 2004, had a combined stock of cattle and sheep equivalent to 36% and 24% of world totals, respectively (FAO, 2003).

Emissions from rice production and burning of biomass were heavily concentrated in the group of developing countries, with 97% and 92% of world totals, respectively. While CH4 emissions from rice occurred mostly in South and East Asia, where it is a dominant food source (82% of total emissions), those from biomass burning originated in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean (74% of total). Manure management was the only source for which emissions where higher in the group of developed regions (52%) than in developing regions (48%; US-EPA, 2006a).

The balance between the large fluxes of CO2 emissions and removals in agricultural land is uncertain. A study by US- EPA (2006b) showed that some countries and regions have net emissions, while others have net removals of CO2. Except for the countries of Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia, which had an annual emission of 26 MtCO2/yr in 2000, all other countries showed very low emissions or removals.

8.3.1 Trends since 1990

Globally, agricultural CH4 and N2O emissions increased by 17% from 1990 to 2005, an average annual emission increase of 58 MtCO2-eq/yr (US-EPA, 2006a). Both gases had about the same share of this increase. Three sources together explained 88% of the increase: biomass burning (N2O and CH4), enteric fermentation (CH4) and soil N2O emissions (US-EPA, 2006a).

During that period, according to US-EPA (2006a; Figure 8.2), the five regions composed of Non-Annex I countries showed a 32% increase in non-CO2 emissions (equivalent to 73 MtCO2-eq/yr).The other five regions, with mostly Annex I countries, collectively showed a decrease of 12% (equivalent to 15 MtCO2-eq/yr). This was mostly due to non-climate macroeconomic policies in the Central and Eastern European and the countries of Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia (see Section 8.7.1 and 8.7.2).

8.3.2 Future global trends

Agricultural N2O emissions are projected to increase by 35-60% up to 2030 due to increased nitrogen fertilizer use and increased animal manure production (FAO, 2003). Similarly, Mosier and Kroeze (2000) and US-EPA (2006a; Figure 8.2) estimated that N2O emissions will increase by about 50% by 2020 (relative to 1990). If demands for food increase, and diets shift as projected, then annual emissions of GHGs from agriculture may escalate further. But improved management practices and emerging technologies may permit a reduction in emissions per unit of food (or protein) produced, and perhaps also a reduction in emissions per capita food consumption.

If CH4 emissions grow in direct proportion to increases in livestock numbers, then global livestock-related methane production is expected to increase by 60% up to 2030 (FAO, 2003). However, changes in feeding practices and manure management could ameliorate this increase. US-EPA (2006a) forecast that combined methane emissions from enteric fermentation and manure management will increase by 21% between 2005 and 2020.

The area of rice grown globally is forecast to increase by 4.5% to 2030 (FAO, 2003), so methane emissions from rice production would not be expected to increase substantially. There may even be reductions if less rice is grown under continuous flooding (causing anaerobic soil conditions) as a result of scarcity of water, or if new rice cultivars that emit less methane are developed and adopted (Wang et al., 1997). However, US-EPA (2006a) projects a 16% increase in CH4 emissions from rice crops between 2005 and 2020, mostly due to a sustained increase in the area of irrigated rice.

No baseline agricultural non-CO2 GHG emission estimates for the year 2030 have been published, but according to US-EPA (2006a), aggregate emissions are projected to increase by ~13% during the decades 2000-2010 and 2010-2020. Assuming similar rates of increase (10-15%) for 2020-2030, agricultural emissions might be expected to rise to 8000–8400, with a mean of 8300 MtCO2-eq by 2030. The future evolution of CO2 emissions from agriculture is uncertain. Due to stable or declining deforestation rates (FAO, 2003), and increased adoption of conservation tillage practices (FAO, 2001), these emissions are likely to decrease or remain at low levels.

8.3.3 Regional trends

The Middle East and North Africa, and Sub-SaharanAfrica have the highest projected growth in emissions, with acombined 95% increase in the period 1990 to 2020 (US-EPA, 2006a). Sub-Saharan Africa is the one world region where per capitafood production is either in decline, or roughly constantat a level that is less than adequate (Scholes and Biggs, 2004).This trend is linked to low and declining soil fertility (Sanchez,2002), and inadequate fertilizer inputs. Although slow, therising wealth of urban populations is likely to increase demandfor livestock products. This would result in intensification ofagriculture and expansion to still largely unexploited areas,particularly in South and Central Africa (including Angola,Zambia, DRC, Mozambique and Tanzania), with a consequentincrease in GHG emissions.

East Asia is projected to show large increases in GHGemissions from animal sources. According to FAO (FAOSTAT,2006), total production of meat and milk in Asian developing countries increased more than 12 times and 4 times, respectively,from 2004 to 1961. Since the per-capita consumption ofmeat and milk is still much lower in these countries than indeveloped countries, increasing trends are expected to continuefor a relatively long time. Accordingly, US-EPA (2006a)forecast increases of 153% and 86% in emissions from entericfermentation and manure management, respectively, from 1990to 2020. In South Asia, emissions are increasing mostly becauseof expanding use of N fertilizers and manure to meet demandsfor food, resulting from rapid population growth.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, agricultural productsare the main source of exports. Significant changes in landuse and management have occurred, with forest conversion to cropland and grassland being the most significant, resultingin increased GHG emissions from soils (CO2 and N2O). Thecattle population has increased linearly from 176 to 379 Mheadbetween 1961 and 2004, partly offset by a decrease in the sheeppopulation from 125 to 80 Mhead. All other livestock categorieshave increased in the order of 30 to 600% since 1961. Croplandareas, including rice and soybean, and the use of N fertilizershave also shown dramatic increases (FAOSTAT, 2006). Anothermajor trend in the region is the increased adoption of no-tillagriculture, particularly in the Mercosur area (Brazil, Argentina,Paraguay, and Uruguay). This technology is used on ~30 Mhaevery year in the region, although it is unknown how much ofthis area is under permanent no-till.

In the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, the Caucasusand Central Asia, agricultural production is, at present, about60-80% of that in 1990, but is expected to grow by 15-40%above 2001 levels by 2010, driven by the increasing wealth ofthese countries. A 10-14% increase in arable land area is forecastfor the whole of Russia due to agricultural expansion. Thewidespread application of intensive management technologiescould result in a 2 to 2.5-fold rise in grain and fodder yields,with a consequent reduction of arable land, but may increase Nfertilizer use. Decreases in fertilizer N use since 1990 have led toa significant reduction in N2O emissions. But, under favourableeconomic conditions, the amount of N fertilizer applied willagain increase, although unlikely to reach pre-1990 levels in thenear future. US-EPA (2006a) projected a 32% increase in N2Oemissions from soils in these two regions between 2005 and2020, equivalent to an average rate of increase of 3.5 MtCO2-eq/yr.

OECD North America and OECD Pacific are the onlydeveloped regions showing a consistent increase in GHGemissions in the agricultural sector (18% and 21%, respectively between 1990 and 2020; Figure 8.2). In both cases, the trend islargely driven by non-CO2 emissions from manure managementand N2O emissions from soils. In Oceania, nitrogen fertilizeruse has increased exponentially over the past 45 years witha 5 and 2.5 fold increase since 1990 in New Zealand andAustralia, respectively. In North America, in contrast, nitrogenfertilizer use has remained stable; the main driver for increasingemissions is management of manure from cattle, poultry andswine production, and manure application to soils. In bothregions, conservation policies have resulted in reduced CO2emissions from land conversion. Land clearing in Australiahas declined by 60% since 1990 with vegetation managementpolicies restricting further clearing, while in North America,some marginal croplands have been returned to woodland orgrassland.

Western Europe is the only region where, according to USEPA(2006a), GHG emissions from agriculture are projectedto decrease to 2020 (Figure 8.2). This is associated with the adoption of a number of climate-specific and other environmentalpolicies in the European Union, as well as economic constraintson agriculture, as discussed in Sections 8.7.1 and 8.7.2.

8.4 Description and assessment ofmitigation technologies andpractices, options and potentials,costs and sustainability

8.4.1 Mitigation technologies and practices

Opportunities for mitigating GHGs in agriculture fall into three broad categories[1], based on the underlying mechanism:

a. Reducing emissions: Agriculture releases to the atmosphere significant amounts of CO2, CH4, or N2O (Cole et al., 1997; IPCC, 2001a; Paustian et al., 2004). The fluxes of these gases can be reduced by more efficient management of carbon and nitrogen flows in agricultural ecosystems. For example, practices that deliver added N more efficiently to crops often reduce N2O emissions (Bouwman, 2001), and managing livestock to make most efficient use of feeds often reduces amounts of CH4 produced (Clemens and Ahlgrimm, 2001). The approaches that best reduce emissions depend on local conditions, and therefore, vary from region to region.

b. Enhancing removals: Agricultural ecosystems hold large carbon reserves (IPCC, 2001a), mostly in soil organic matter. Historically, these systems have lost more than 50 Pg C (Paustian et al., 1998; Lal, 1999, 2004a), but some of this carbon lost can be recovered through improved management, thereby withdrawing atmospheric CO2. Any practice that increases the photosynthetic input of carbon and/or slows the return of stored carbon to CO2 via respiration, fire or erosion will increase carbon reserves, thereby ‘sequestering’ carbon or building carbon ‘sinks’. Many studies, worldwide, have now shown that significant amounts of soil carbon can be stored in this way, through a range of practices, suited to local conditions (Lal, 2004a). Significant amounts of vegetative carbon can also be stored in agro-forestry systems or other perennial plantings on agricultural lands (Albrecht and Kandji, 2003). Agricultural lands also remove CH4 from the atmosphere by oxidation (but less than forests; Tate et al., 2006), but this effect is small compared to other GHG fluxes (Smith and Conen, 2004).

c. Avoiding (or displacing) emissions: Crops and residues from agricultural lands can be used as a source of fuel, either directly or after conversion to fuels such as ethanol or diesel (Schneider and McCarl, 2003; Cannell, 2003). These bio-energy feedstocks still release CO2 upon combustion, but now the carbon is of recent atmospheric origin (via photosynthesis), rather than from fossil carbon. The net benefit of these bio-energy sources to the atmosphere is equal to the fossil-derived emissions displaced, less any emissions from producing, transporting, and processing. GHG emissions, notably CO2, can also be avoided by agricultural management practices that forestall the cultivation of new lands now under forest, grassland, or other non-agricultural vegetation (Foley et al., 2005).

Many practices have been advocated to mitigate emissions through the mechanisms cited above. Often, a practice will affect more than one gas, by more than one mechanism, sometimes in opposite ways, so the net benefit depends on the combined effects on all gases (Robertson and Grace, 2004; Schils et al., 2005; Koga et al., 2006). In addition, the temporal pattern of influence may vary among practices or among gases for a given practice; some emissions are reduced indefinitely, other reductions are temporary (Six et al., 2004; Marland et al., 2003a). Where a practice affects radiative forcing through other mechanisms such as aerosols or albedo, those impacts also need to be considered (Marland et al., 2003b; Andreae et al., 2005).

The impacts of the mitigation options considered are summarized qualitatively in Table 8.3. Although comprehensive life-cycle analyses are not always possible, given the complexity of many farming systems, the table also includes estimates of the confidence based on expert opinion that the practice can reduce overall net emissions at the site of adoption. Some of these practices also have indirect effects on ecosystems elsewhere. For example, increased productivity in existing croplands could avoid deforestation and its attendant emissions (see also Section 8.8). The most important options are discussed in Section 8.4.1.

Table 8.3: Proposed measures for mitigating greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural ecosystems, their apparent effects on reducing emissions of individual gases where adopted (mitigative effect), and an estimate of scientific confidence that the proposed practice can reduce overall net emissions at the site of adoption.

| Mitigative effectsa | Net mitigationb (confidence) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Examples | CO2 | CH4 | N2O | Agreement | Evidence |

| Cropland management | Agronomy | + | +/- | *** | ** | |

| Nutrient management | + | + | *** | ** | ||

| Tillage/residue management | + | +/- | ** | ** | ||

| Water management (irrigation, drainage) | +/- | + | * | * | ||

| Rice management | +/- | + | +/- | ** | ** | |

| Agro-forestry | + | +/- | *** | * | ||

| Set-aside, land-use change | + | + | + | *** | *** | |

| Grazing land management/ pasture improvement | Grazing intensity | +/- | +/- | +/- | * | * |

| Increased productivity (e.g., fertilization) | + | +/- | ** | * | ||

| Nutrient management | + | +/- | ** | ** | ||

| Fire management | + | + | +/- | * | * | |

| Species introduction (including legumes) | + | +/- | * | ** | ||

| Management of organic soils | Avoid drainage of wetlands | + | - | +/- | ** | ** |

| Restoration of degraded lands | Erosion control, organic amendments, nutrient amendments | + | +/- | *** | ** | |

| Livestock management | Improved feeding practices | + | + | *** | *** | |

| Specific agents and dietary additives | + | ** | *** | |||

| Longer term structural and management changes and animal breeding | + | + | ** | * | ||

| Manure/biosolid management | Improved storage and handling | + | +/- | *** | ** | |

| Anaerobic digestion | + | +/- | *** | * | ||

| More efficient use as nutrient source | + | + | *** | ** | ||

| Bio-energy | Energy crops, solid, liquid, biogas, residues | + | +/- | +/- | *** | ** |

|

Notes: | ||||||

8.4.1.1 Cropland management

Because often intensively managed, croplands offer many opportunities to impose practices that reduce net GHG emissions (Table 8.3). Mitigation practices in cropland management include the following partly-overlapping categories:

a. Agronomy: Improved agronomic practices that increase yields and generate higher inputs of carbon residue can lead to increased soil carbon storage (Follett, 2001). Examples of such practices include: using improved crop varieties; extending crop rotations, notably those with perennial crops that allocate more carbon below ground; and avoiding or reducing use of bare (unplanted) fallow (West and Post, 2002; Smith, 2004a, b; Lal, 2003, 2004a; Freibauer et al., 2004). Adding more nutrients, when deficient, can also promote soil carbon gains (Alvarez, 2005), but the benefits from N fertilizer can be offset by higher N2O emissions from soils and CO2 from fertilizer manufacture (Schlesinger, 1999; Pérez-Ramírez et al., 2003; Robertson, 2004; Gregorich et al., 2005). Emissions per hectare can also be reduced by adopting cropping systems with reduced reliance on fertilizers, pesticides and other inputs (and therefore, the GHG cost of their production: Paustian et al., 2004). An important example is the use of rotations with legume crops (West and Post, 2002; Izaurralde et al., 2001), which reduce reliance on external N inputs although legume-derived N can also be a source of N2O (Rochette and Janzen, 2005). Another group of agronomic practices are those that provide temporary vegetative cover between successive agricultural crops, or between rows of tree or vine crops. These ‘catch’ or ‘cover’ crops add carbon to soils (Barthès et al., 2004; Freibauer et al., 2004) and may also extract plant-available N unused by the preceding crop, thereby reducing N2O emissions.

b. Nutrient management: Nitrogen applied in fertilizers, manures, biosolids, and other N sources is not always used efficiently by crops (Galloway et al., 2003; Cassman et al., 2003). The surplus N is particularly susceptible to emission of N2O (McSwiney and Robertson, 2005). Consequently, improving N use efficiency can reduce N2O emissions and indirectly reduce GHG emissions from N fertilizer manufacture (Schlesinger, 1999). By reducing leaching and volatile losses, improved efficiency of N use can also reduce off-site N2O emissions. Practices that improve N use efficiency include: adjusting application rates based on precise estimation of crop needs (e.g., precision farming); using slow- or controlled-release fertilizer forms or nitrification inhibitors (which slow the microbial processes leading to N2O formation); applying N when least susceptible to loss, often just prior to plant uptake (improved timing); placing the N more precisely into the soil to make it more accessible to crops roots; or avoiding N applications in excess of immediate plant requirements (Robertson, 2004; Dalal et al., 2003; Paustian et al., 2004; Cole et al., 1997; Monteny et al., 2006).

c. Tillage/residue management: Advances in weed control methods and farm machinery now allow many crops to be grown with minimal tillage (reduced tillage) or without tillage (no-till). These practices are now increasingly used throughout the world (e.g., Cerri et al., 2004). Since soil disturbance tends to stimulate soil carbon losses through enhanced decomposition and erosion (Madari et al., 2005), reduced- or no-till agriculture often results in soil carbon gain, but not always (West and Post, 2002; Ogle et al., 2005; Gregorich et al., 2005; Alvarez 2005). Adopting reduced- or no-till may also affect N2O, emissions but the net effects are inconsistent and not well-quantified globally (Smith and Conen, 2004; Helgason et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005; Cassman et al., 2003). The effect of reduced tillage on N2O emissions may depend on soil and climatic conditions. In some areas, reduced tillage promotes N2O emissions, while elsewhere it may reduce emissions or have no measurable influence (Marland et al., 2001). Further, no-tillage systems can reduce CO2 emissions from energy use (Marland et al., 2003b; Koga et al., 2006). Systems that retain crop residues also tend to increase soil carbon because these residues are the precursors for soil organic matter, the main carbon store in soil. Avoiding the burning of residues (e.g., mechanising sugarcane harvesting, eliminating the need for pre-harvest burning (Cerri et al., 2004)) also avoids emissions of aerosols and GHGs generated from fire, although CO2 emissions from fuel use may increase.

d. Water management: About 18% of the world’s croplands now receive supplementary water through irrigation (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005). Expanding this area (where water reserves allow) or using more effective irrigation measures can enhance carbon storage in soils through enhanced yields and residue returns (Follett, 2001; Lal, 2004a). But some of these gains may be offset by CO2 from energy used to deliver the water (Schlesinger 1999; Mosier et al., 2005) or from N2O emissions from higher moisture and fertilizer N inputs (Liebig et al. 2005), The latter effect has not been widely measured. Drainage of croplands lands in humid regions can promote productivity (and hence soil carbon) and perhaps also suppress N2O emissions by improving aeration (Monteny et al., 2006). Any nitrogen lost through drainage, however, may be susceptible to loss as N2O.(Reay et al. 2003).

e. Rice management: Cultivated wetland rice soils emit significant quantities of methane (Yan et al., 2003). Emissions during the growing season can be reduced by various practices (Yagi et al., 1997; Wassmann et al., 2000; Aulakh et al., 2001). For example, draining wetland rice once or several times during the growing season reduces CH4 emissions (Smith and Conen, 2004; Yan et al., 2003; Khalil and Shearer, 2006). This benefit, however, may be partly offset by increased N2O emissions (Akiyama et al. 2005), and the practice may be constrained by water supply. Rice cultivars with low exudation rates could offer an important methane mitigation option (Aulakh et al., 2001). In the off-rice season, methane emissions can be reduced by improved water management, especially by keeping the soil as dry as possible and avoiding water logging (Cai et al., 2000 2003; Kang et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2003). Increasing rice production can also enhance soil organic carbon stocks (Pan et al., 2006). Methane emissions can be reduced by adjusting the timing of organic residue additions (e.g., incorporating organic materials in the dry period rather than in flooded periods; Xu et al., 2000; Cai and Xu, 2004), by composting the residues before incorporation, or by producing biogas for use as fuel for energy production (Wang and Shangguan, 1996; Wassmann et al., 2000).

f. Agro-forestry: Agro-forestry is the production of livestock or food crops on land that also grows trees for timber, firewood, or other tree products. It includes shelter belts and riparian zones/buffer strips with woody species. The standing stock of carbon above ground is usually higher than the equivalent land use without trees, and planting trees may also increase soil carbon sequestration (Oelbermann et al., 2004; Guo and Gifford, 2002; Mutuo et al., 2005; Paul et al., 2003). But the effects on N2O and CH4 emissions are not well known (Albrecht and Kandji, 2003).

g. Land cover (use) change: One of the most effective methods of reducing emissions is often to allow or encourage the reversion of cropland to another land cover, typically one similar to the native vegetation. The conversion can occur over the entire land area (‘set-asides’), or in localized spots, such as grassed waterways, field margins, or shelterbelts (Follett, 2001; Freibauer et al., 2004; Lal, 2004b; Falloon et al., 2004; Ogle et al., 2003). Such land cover change often increases carbon storage. For example, converting arable cropland to grassland typically results in the accrual of soil carbon because of lower soil disturbance and reduced carbon removal in harvested products. Compared to cultivated lands, grasslands may also have reduced N2O emissions from lower N inputs, and higher rates of CH4 oxidation, but recovery of oxidation may be slow (Paustian et al., 2004). Similarly, converting drained croplands back to wetlands can result in rapid accumulation of soil carbon (removal of atmospheric CO2). This conversion may stimulate CH4 emissions because water logging creates anaerobic conditions (Paustian et al., 2004). Planting trees can also reduce emissions. These practices are considered under agro-forestry (Section 8.4.1.1f); afforestation (Chapter 9), and reafforestation (Chapter 9). Because land cover (or use) conversion comes at the expense of lost agricultural productivity, it is usually an option only on surplus agricultural land or on croplands of marginal productivity.

8.4.1.2 Grazing land management and pasture improvement

Grazing lands occupy much larger areas than croplands (FAOSTAT, 2006) and are usually managed less intensively. The following are examples of practices to reduce GHG emissions and to enhance removals:

a. Grazing intensity: The intensity and timing of grazing can influence the removal, growth, carbon allocation, and flora of grasslands, thereby affecting the amount of carbon accrual in soils (Conant et al., 2001; 2005; Freibauer et al., 2004; Conant and Paustian, 2002; Reeder et al., 2004). Carbon accrual on optimally grazed lands is often greater than on ungrazed or overgrazed lands (Liebig et al., 2005; Rice and Owensby, 2001). The effects are inconsistent, however, owing to the many types of grazing practices employed and the diversity of plant species, soils, and climates involved (Schuman et al., 2001; Derner et al., 2006). The influence of grazing intensity on emission of non-CO2 gases is not well-established, apart from the direct effects on emissions from adjustments in livestock numbers.

b. Increased productivity: (including fertilization): As for croplands, carbon storage in grazing lands can be improved by a variety of measures that promote productivity. For instance, alleviating nutrient deficiencies by fertilizer or organic amendments increases plant litter returns and, hence, soil carbon storage (Schnabel et al., 2001; Conant et al., 2001). Adding nitrogen, however, often stimulates N2O emissions (Conant et al., 2005) thereby offsetting some of the benefits. Irrigating grasslands, similarly, can promote soil carbon gains (Conant et al., 2001). The net effect of this practice, however, depends also on emissions from energy use and other activities on the irrigated land (Schlesinger, 1999).

c. Nutrient management: Practices that tailor nutrient additions to plant uptake, such as those described for croplands, can reduce N2O emissions (Dalal et al., 2003; Follett et al., 2001). Management of nutrients on grazing lands, however, may be complicated by deposition of faeces and urine from livestock, which are not as easily controlled nor as uniformly applied as nutritive amendments in croplands (Oenema et al., 2005).

d. Fire management: On-site biomass burning (not to be confused with bio-energy, where biomass is combusted off-site for energy) contributes to climate change in several ways. Firstly, it releases GHGs, notably CH4 and, and to a lesser extent, N2O (the CO2 released is of recent origin, is absorbed by vegetative regrowth, and is usually not included in GHG inventories). Secondly, it generates hydrocarbon and reactive nitrogen emissions, which react to form tropospheric ozone, a powerful GHG. Thirdly, fires produce a range of smoke aerosols which can have either warming or cooling effects on the atmosphere; the net effect is thought to be positive radiative forcing (Andreae et al., 2005; Jones et al., 2003; Venkataraman et al., 2005; Andreae, 2001; Andreae and Merlet, 2001; Anderson et al., 2003; Menon et al., 2002). Fourth, fire reduces the albedo of the land surface for several weeks, causing warming (Beringer et al., 2003). Finally, burning can affect the proportion of woody versus grass cover, notably in savannahs, which occupy about an eighth of the global land surface. Reducing the frequency or intensity of fires typically leads to increased tree and shrub cover, resulting in a CO2 sink in soil and biomass (Scholes and van der Merwe, 1996). This woody-plant encroachment mechanism saturates over 20-50 years, whereas avoided CH4 and N2O emissions continue as long as fires are suppressed. Mitigation actions involve reducing the frequency or extent of fires through more effective fire suppression; reducing the fuel load by vegetation management; and burning at a time of year when less CH4 and N2O are emitted (Korontzi et al., 2003). Although most agricultural-zone fires are ignited by humans, there is evidence that the area burned is ultimately under climatic control (Van Wilgen et al., 2004). In the absence of human ignition, the fire-prone ecosystems would still burn as a result of climatic factors.

e. Species introduction: Introducing grass species with higher productivity, or carbon allocation to deeper roots, has been shown to increase soil carbon. For example, establishing deep-rooted grasses in savannahs has been reported to yield very high rates of carbon accrual (Fisher et al., 1994), although the applicability of these results has not been widely confirmed (Conant et al., 2001; Davidson et al., 1995). In the Brazilian Savannah (Cerrado Biome), integrated crop-livestock systems using Brachiaria grasses and zero tillage are being adopted (Machado and Freitas, 2004). Introducing legumes into grazing lands can promote soil carbon storage (Soussana et al., 2004), through enhanced productivity from the associated N inputs, and perhaps also reduced emissions from fertilizer manufacture if biological N2 fixation displaces applied N fertilizer N (Sisti et al., 2004; Diekow et al., 2005). Ecological impacts of species introduction need to be considered.

Grazing lands also emit GHGs from livestock, notably CH4 from ruminants and their manures. Practices for reducing these emissions are considered under Section 8.4.1.5: Livestock management.

8.4.1.3 Management of organic/peaty soils

Organic or peaty soils contain high densities of carbon accumulated over many centuries because decomposition is suppressed by absence of oxygen under flooded conditions. To be used for agriculture, these soils are drained, which aerates the soil, favouring decomposition and therefore, high CO2 and N2O fluxes. Methane emissions are usually suppressed after draining, but this effect is far outweighed by pronounced increases in N2O and CO2 (Kasimir-Klemedtsson et al., 1997). Emissions from drained organic soils can be reduced to some extent by practices such as avoiding row crops and tubers, avoiding deep ploughing, and maintaining a shallower water table. But the most important mitigation practice is avoiding the drainage of these soils in the first place or re-establishing a high water table (Freibauer et al., 2004).

8.4.1.4 Restoration of degraded lands

A large proportion of agricultural lands has been degraded by excessive disturbance, erosion, organic matter loss, salinization, acidification, or other processes that curtail productivity (Batjes, 1999; Foley et al., 2005; Lal, 2001a, 2003, 2004b). Often, carbon storage in these soils can be partly restored by practices that reclaim productivity including: re-vegetation (e.g., planting grasses); improving fertility by nutrient amendments; applying organic substrates such as manures, biosolids, and composts; reducing tillage and retaining crop residues; and conserving water (Lal, 2001b; 2004b; Bruce et al., 1999; Olsson and Ardö, 2002; Paustian et al., 2004). Where these practices involve higher nitrogen amendments, the benefits of carbon sequestration may be partly offset by higher N2O emissions.

8.4.1.5 Livestock management

Livestock, predominantly ruminants such as cattle and sheep, are important sources of CH4, accounting for about one-third of global anthropogenic emissions of this gas (US-EPA, 2006a). The methane is produced primarily by enteric fermentation and voided by eructation (Crutzen, 1995; Murray et al., 1976; Kennedy and Milligan, 1978). All livestock generate N2O emissions from manure as a result of excretion of N in urine and faeces. Practices for reducing CH4 and N2O emissions from this source fall into three general categories: improved feeding practices, use of specific agents or dietary additives; and longer-term management changes and animal breeding (Soliva et al., 2006; Monteny et al., 2006).

a. Improved feeding practices: Methane emissions can be reduced by feeding more concentrates, normally replacing forages (Blaxter and Claperton, 1965; Johnson and Johnson, 1995; Lovett et al., 2003; Beauchemin and McGinn, 2005). Although concentrates may increase daily methane emissions per animal, emissions per kg-feed intake and per kg-product are almost invariably reduced. The magnitude of this reduction per kg-product decreases as production increases. The net benefit of concentrates, however, depends on reduced animal numbers or younger age at slaughter for beef animals, and on how the practice affects land use, the N content of manure and emissions from producing and transporting the concentrates (Phetteplace et al., 2001; Lovett et al., 2006). Other practices that can reduce CH4 emissions include: adding certain oils or oilseeds to the diet (e.g., Machmüller et al., 2000; Jordan et al., 2006c); improving pasture quality, especially in less developed regions, because this improves animal productivity, and reduces the proportion of energy lost as CH4 (Leng, 1991; McCrabb et al., 1998; Alcock and Hegarty, 2006); and optimizing protein intake to reduce N excretion and N2O emissions (Clark et al., 2005).

b. Specific agents and dietary additives: A wide range of specific agents, mostly aimed at suppressing methanogenesis, has been proposed as dietary additives to reduce CH4 emissions:

Ionophores are antibiotics that can reduce methane emissions (Benz and Johnson, 1982; Van Nevel and Demeyer, 1996; McGinn et al., 2004), but their effect may be transitory (Rumpler et al., 1986); and they have been banned in the EU.

Halogenated compounds inhibit methanogenic bacteria (Wolin et al., 1964; Van Nevel and Demeyer, 1995) but their effects, too, are often transitory and they can have side-effects such as reduced intake.

Novel plant compounds such as condensed tannins (Pinares-Patiño et al., 2003; Hess et al., 2006), saponins (Lila et al., 2003) or essential oils (Patra et al., 2006; Kamra et al., 2006) may have merit in reducing methane emissions, but these responses may often be obtained through reduced digestibility of the diet.

Probiotics, such as yeast culture, have shown only small, insignificant effects (McGinn et al., 2004), but selecting strains specifically for methane-reducing ability could improve results (Newbold and Rode, 2006).

Propionate precursors such as fumarate or malate reduce methane formation by acting as alternative hydrogen acceptors (Newbold et al., 2002). But as response is elicited only at high doses, propionate precursors are, therefore, expensive (Newbold et al., 2005).

Vaccines against methanogenic bacteria are being developed but are not yet available commercially (Wright et al., 2004).

Bovine somatotropin (bST) and hormonal growth implants do not specifically suppress CH4 formation, but by improving animal performance (Bauman, 1992; Schmidely, 1993), they can reduce emissions per-kg of animal product (Johnson et al., 1991; McCrabb, 2001).

c. Longer-term management changes and animal breeding: Increasing productivity through breeding and better management practices, such as a reduction in the number of replacement heifers, often reduces methane output per unit of animal product (Boadi et al., 2004). Although selecting cattle directly for reduced methane production has been proposed (Kebreab et al., 2006), it is still impractical due to difficulties in accurately measuring methane emissions at a magnitude suitable for breeding programmes. With improved efficiency, meat-producing animals reach slaughter weight at a younger age, with reduced lifetime emissions (Lovett and O’Mara, 2002). However, the whole-system effects of such practices may not always lead to reduced emissions. For example in dairy cattle, intensive selection for higher yield may reduce fertility, requiring more replacement heifers in the herd (Lovett et al., 2006).

8.4.1.6 Manure management

Animal manures can release significant amounts of N2O and CH4 during storage, but the magnitude of these emissions varies. Methane emissions from manure stored in lagoons or tanks can be reduced by cooling, use of solid covers, mechanically separating solids from slurry, or by capturing the CH4 emitted (Amon et al. 2006; Clemens and Ahlgrimm, 2001; Monteny et al. 2001, 2006; Paustian et al., 2004). The manures can also be digested anaerobically to maximize CH4 retrieval as a renewable energy source (Clemens and Ahlgrimm, 2001; Clemens et al., 2006). Handling manures in solid form (e.g., composting) rather than liquid form can suppress CH4 emissions, but may increase N2O formation (Paustian et al., 2004). Preliminary evidence suggests that covering manure heaps can reduce N2O emissions, but the effect of this practice on CH4 emissions is variable (Chadwick, 2005). For most animals, worldwide there is limited opportunity for manure management, treatment, or storage; excretion happens in the field and handling for fuel or fertility amendment occurs when it is dry and methane emissions are negligible (Gonzalez-Avalos and Ruiz-Suarez, 2001). To some extent, emissions from manure might be curtailed by altering feeding practices (Külling et al., 2003; Hindrichsen et al., 2006; Kreuzer and Hindrichsen, 2006), or by composting the manure (Pattey et al., 2005; Amon et al., 2001), but if aeration is inadequate CH4 emissions during composting can still be substantial (Xu et al., 2007). All of these practices require further study from the perspective of their impact on whole life-cycle GHG emissions.

Manures also release GHGs, notably N2O, after application to cropland or deposition on grazing lands. Practices for reducing these emissions are considered in Subsection 8.4.1.1: Cropland management and Subsection 8.4.1.2: Grazing land management.

8.4.1.7 Bioenergy

Increasingly, agricultural crops and residues are seen as sources of feedstocks for energy to displace fossil fuels. A wide range of materials have been proposed for use, including grain, crop residue, cellulosic crops (e.g., switchgrass, sugarcane), and various tree species (Edmonds, 2004; Cerri et al., 2004; Paustian et al., 2004; Sheehan et al., 2004; Dias de Oliveira et al., 2005; Eidman, 2005). These products can be burned directly, but can also be processed further to generate liquid fuels such as ethanol or diesel fuel (Richter, 2004). Such fuels release CO2 when burned, but this CO2 is of recent atmospheric origin (via photosynthetic carbon uptake) and displaces CO2 which otherwise would have come from fossil carbon. The net benefit to atmospheric CO2, however, depends on energy used in growing and processing the bioenergy feedstock (Spatari et al., 2005).

The competition for other land uses and the environmental impacts need to be considered when planning to use energy crops (e.g., European Environment Agency, 2006). The interactions of an expanding bioenergy sector with other land uses, and impacts on agro-ecosystem services such as food production, biodiversity, soil and nature conservation, and carbon sequestration have not yet been adequately studied, but bottom:up approaches (Smeets et al., 2007) and integrated assessment modelling (Hoogwijk et al., 2005; Hoogwijk, 2004) offer opportunities to improve understanding. Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Eastern Europe are promising regions for bio-energy, with additional long-term contributions from Oceania and East and Northeast Asia. The technical potential for biomass production may be developed at low production costs in the range of 2 US$/GJ (Hoogwijk, 2004; Rogner et al., 2000).

Major transitions are required to exploit the large potential for bioenergy. Improving agricultural efficiency in developing countries is a key factor. It is still uncertain to what extent, and how fast, such transitions could be realized in different regions. Under less favourable conditions, the regional bio-energy potential(s) could be quite low. Also, technological developments in converting biomass to energy, as well as long distance biomass supply chains (e.g., those involving intercontinental transport of biomass derived energy carriers) can dramatically improve competitiveness and efficiency of bio-energy (Faaij, 2006; Hamelinck et al., 2004).

8.4.2 Mitigation technologies and practices: per-area estimates of potential

As mitigation practices can affect more than one GHG[2], it is important to consider the impact of mitigation options on all GHGs (Robertson et al,. 2000; Smith et al., 2001; Gregorich et al., 2005). For non-livestock mitigation options, ranges for per-area mitigation potentials of each GHG are provided in Table 8.4 (tCO2-eq/ha/yr).

Mitigation potentials for CO2 represent the net change in soil carbon pools, reflecting the accumulated difference between carbon inputs to the soil after CO2 uptake by plants, and release of CO2 by decomposition in soil. Mitigation potentials for N2O and CH4 depend solely on emission reductions. Soil carbon stock changes were derived from about 200 studies, and the emission ranges for CH4 and N2O were derived using the DAYCENT and DNDC simulation models (IPCC, 2006; US-EPA, 2006b; Smith et al., 2007b; Ogle et al., 2004, 2005).

Table 8.5 presents the mitigation potentials in livestock (dairy cows, beef cattle, sheep, dairy buffalo and other buffalo) for reducing enteric methane emissions via improved feeding practices, specific agents and dietary additives, and longer term structural and management changes/animal breeding. These estimates were derived by Smith et al. (2007a) using a model similar to that described in US-EPA (2006b).

Some mitigation measures operate predominantly on one GHG (e.g., dietary management of ruminants to reduce CH4 emissions) while others have impacts on more than one GHG (e.g., rice management). Moreover, practices may benefit more than one gas (e.g., set-aside/headland management) while others involve a trade-off between gases (e.g., restoration of organic soils). The effectiveness of non-livestock mitigation options are variable across and within climate regions (see Table 8.4). Consequently, a practice that is highly effective in reducing emissions at one site may be less effective or even counter-productive elsewhere. Similarly, effectiveness of livestock options also varies regionally (Table 8.5). This means that there is no universally applicable list of mitigation practices, but that proposed practices will need to be evaluated for individual agricultural systems according to the specific climatic, edaphic, social settings, and historical land use and management. Assessments can be conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of practices in specific areas, building on findings from the global scale assessment reported here. In addition, such assessments could address GHG emissions associated with energy use and other inputs (e.g., fuel, fertilizers, and pesticides) in a full life cycle analysis for the production system.

Table 8.4: Annual mitigation potentials in each climate region for non-livestock mitigation options

| Climate zone | Activity | Practice | CO2 (tCO2/ha/yr) | CH4 (tCO2-eq/ha/yr) | N2O (tCO2-eq/ha/yr) | All GHG (tCO2-eq/ha/yr) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean estimate | Low | High | Mean estimate | Low | High | Mean estimate | Low | High | Mean estimate | Low | High | |||

| Cool-dry | Croplands | Agronomy | 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.51 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.39 | 0.07 | 0.71 |

| Croplands | Nutrient management | 0.26 | -0.22 | 0.73 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.33 | -0.21 | 1.05 | |

| Croplands | Tillage and residue management | 0.15 | -0.48 | 0.77 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | -0.04 | 0.09 | 0.17 | -0.52 | 0.86 | |

| Croplands | Water management | 1.14 | -0.55 | 2.82 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.14 | -0.55 | 2.82 | |

| Croplands | Set-aside and LUC | 1.61 | -0.07 | 3.30 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.30 | 0.00 | 4.60 | 3.93 | -0.07 | 7.90 | |

| Croplands | Agro-forestry | 0.15 | -0.48 | 0.77 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | -0.04 | 0.09 | 0.17 | -0.52 | 0.86 | |

| Grasslands | Grazing, fertilization, fire | 0.11 | -0.55 | 0.77 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.13 | -0.54 | 0.79 | |

| Organic soils | Restoration | 36.67 | 3.67 | 69.67 | -3.32 | -0.05 | -15.30 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 33.51 | 3.67 | 54.65 | |

| Degraded lands | Restoration | 3.45 | -0.37 | 7.26 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.53 | -0.33 | 7.40 | |

| Manure/biosolids | Application | 1.54 | -3.19 | 6.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.17 | 1.30 | 1.54 | -3.36 | 7.57 | |

| Bioenergy | Soils only | 0.15 | -0.48 | 0.77 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | -0.04 | 0.09 | 0.17 | -0.52 | 0.86 | |

| Cool-moist | Croplands | Agronomy | 0.88 | 0.51 | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.98 | 0.51 | 1.45 |

| Croplands | Nutrient management | 0.55 | 0.01 | 1.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.62 | 0.02 | 1.42 | |

| Croplands | tillage and residue management | 0.51 | 0.00 | 1.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | -0.04 | 0.09 | 0.53 | -0.04 | 1.12 | |

| Croplands | Water management | 1.14 | -0.55 | 2.82 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.14 | -0.55 | 2.82 | |

| Croplands | Set-aside and LUC | 3.04 | 1.17 | 4.91 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.30 | 0.00 | 4.60 | 5.36 | 1.17 | 9.51 | |

| Croplands | Agro-forestry | 0.51 | 0.00 | 1.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | -0.04 | 0.09 | 0.53 | -0.04 | 1.12 | |

| Grasslands | Grazing, fertilization, fire | 0.81 | 0.11 | 1.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 0.11 | 1.50 | |

| Organic soils | Restoration | 36.67 | 3.67 | 69.67 | -3.32 | -0.05 | -15.30 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 33.51 | 3.67 | 54.65 | |

| Degraded lands | Restoration | 3.45 | -0.37 | 7.26 | 1.00 | 0.69 | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.45 | 0.32 | 8.51 | |

| Manure/biosolids | Application | 2.79 | -0.62 | 6.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.17 | 1.30 | 2.79 | -0.79 | 7.50 | |

| Bioenergy | Soils only | 0.51 | 0.00 | 1.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | -0.04 | 0.09 | 0.53 | -0.04 | 1.12 | |

| Warm-dry | Croplands | Agronomy | 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.51 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.39 | 0.07 | 0.71 |

| Croplands | Nutrient management | 0.26 | -0.22 | 0.73 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.33 | -0.21 | 1.05 | |

| Croplands | Tillage and residue management | 0.33 | -0.73 | 1.39 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | -0.04 | 0.09 | 0.35 | -0.77 | 1.48 | |

| Croplands | Water management | 1.14 | -0.55 | 2.82 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.14 | -0.55 | 2.82 | |

| Croplands | Set-aside and LUC | 1.61 | -0.07 | 3.30 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.30 | 0.00 | 4.60 | 3.93 | -0.07 | 7.90 | |

| Croplands | Agro-forestry | 0.33 | -0.73 | 1.39 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | -0.04 | 0.09 | 0.35 | -0.77 | 1.48 | |

| Grasslands | Grazing, fertilization, fire | 0.11 | -0.55 | 0.77 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 | -0.55 | 0.77 | |

| Organic soils | Restoration | 73.33 | 7.33 | 139.33 | -3.32 | -0.05 | -15.30 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 70.18 | 7.33 | 124.31 | |

| Degraded lands | Restoration | 3.45 | -0.37 | 7.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.45 | -0.37 | 7.26 | |

| Manure/biosolids | Application | 1.54 | -3.19 | 6.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.17 | 1.30 | 1.54 | -3.36 | 7.57 | |

| Bioenergy | Soils only | 0.33 | -0.73 | 1.39 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | -0.04 | 0.09 | 0.35 | -0.77 | 1.48 | |

| Warm-moist | Croplands | Agronomy | 0.88 | 0.51 | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.98 | 0.51 | 1.45 |

| Croplands | Nutrient management | 0.55 | 0.01 | 1.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.62 | 0.02 | 1.42 | |

| Croplands | Tillage and residue management | 0.70 | -0.40 | 1.80 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | -0.04 | 0.09 | 0.72 | -0.44 | 1.89 | |

| Croplands | Water management | 1.14 | -0.55 | 2.82 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.14 | -0.55 | 2.82 | |

| Croplands | Set-aside and LUC | 3.04 | 1.17 | 4.91 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.30 | 0.00 | 4.60 | 5.36 | 1.17 | 9.51 | |

| Croplands | Agro-forestry | 0.70 | -0.40 | 1.80 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | -0.04 | 0.09 | 0.72 | -0.44 | 1.89 | |

| Grasslands | Grazing, fertilization, fire | 0.81 | 0.11 | 1.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.81 | 0.11 | 1.50 | |

| Organic soils | Restoration | 73.33 | 7.33 | 139.33 | -3.32 | -0.05 | -15.30 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 70.18 | 7.33 | 124.31 | |

| Degraded lands | Restoration | 3.45 | -0.37 | 7.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.45 | -0.37 | 7.26 | |

| Manure/biosolids | Application | 2.79 | -0.62 | 6.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.17 | 1.30 | 2.79 | -0.79 | 7.50 | |

| Bioenergy | Soils only | 0.70 | -0.40 | 1.80 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | -0.04 | 0.09 | 0.72 | -0.44 | 1.89 | |

|

Notes: | ||||||||||||||

Table 8.5: Technical reduction potential (proportion of an animal’s enteric methane production) for enteric methane emissions due to (i) improved feeding practices, (ii) specific agents and dietary additives and (iii) longer term structural/management change and animal breedinga

| Improved feeding practicesb | Specific agents and dietary additivesc | Longer term structural/management change and animal breedingd | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AEZ regions | Dairy cows | Beef cattle | Sheep | Dairy buffalo | Non-dairy buffalo | Dairy cows | Beef cattle | Sheep | Dairy buffalo | Non-dairy buffalo | Dairy cows | Beef cattle | Sheep | Dairy buffalo | Non-dairy buffalo |

| Northern Europe | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.004 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.003 | ||||||

| Southern. Europe | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.004 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.003 | ||||||

| Western Europe | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.004 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.003 | ||||||

| Eastern. Europe | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.002 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.003 | ||||||

| Russian Federation | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.002 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.003 | ||||||

| Japan | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.004 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.003 | ||||||

| South Asia | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.0005 | 0.01 | 0.002 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| East Asia | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.002 | 0.03 | 0.012 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.003 | 0.03 | 0.07 |

| West Asia | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Southeast Asia | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Central Asia | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Oceania | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.004 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.004 | ||||||

| North America | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.004 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.003 | ||||||

| South America | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.002 | ||||||

| Central America | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.002 | ||||||

| East Africa | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.0002 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.0004 | ||||||

| West Africa | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.0002 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.0004 | ||||||

| North Africa | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.0002 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.0004 | ||||||

| South Africa | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.0002 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.0004 | ||||||

| Middle Africa | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.0002 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.0004 | ||||||

|

Notes: b Includes replacing roughage with concentrate (Blaxter & Claperton, 1965; Moe & Tyrrell, 1979; Johnson & Johnson, 1995; Yan et al., 2000; Mills et al., 2003; Beauchemin & McGinn, 2005; Lovett et al., 2006), improving forages/inclusion of legumes (Leng, 1991; McCrabb et al., 1998; Woodward et al., 2001; Waghorn et al., 2002; Pinares-Patiño et al., 2003; Alcock & Hegarty, 2006) and feeding extra dietary oil (Machmüller et al., 2000; Dohme et al., 2001; Machmüller et al., 2003, Lovett et al., 2003; McGinn et al., 2004; Beauchemin & McGinn, 2005; Jordan et al., 2006a; Jordan et al., 2006b; Jordan et al., 2006c). c Includes bST (Johnson et al., 1991; Bauman, 1992), growth hormones (McCrabb, 2001), ionophores (Benz & Johnson, 1982; Rumpler et al., 1986; Van Nevel & Demeyer, 1996; McGinn et al., 2004), propionate precursors (McGinn et al., 2004; Beauchemin & McGinn, 2005; Newbold et al., 2005; Wallace et al., 2006). d Includes lifetime management of beef cattle (Johnson et al., 2002; Lovett & O’Mara, 2002) and improved productivity through animal breeding (Ferris et al., 1999; Hansen, 2000; Robertson and Waghorn, 2002; Miglior et al., 2005). Source: adapted from Smith et al., 2007a. | |||||||||||||||

The effectiveness of mitigation strategies also changes with time. Some practices, like those which elicit soil carbon gain, have diminishing effectiveness after several decades; others such as methods that reduce energy use may reduce emissions indefinitely. For example, Six et al. (2004) found a strong time dependency of emissions from no-till agriculture, in part because of changing influence of tillage on N2O emissions.

8.4.3 Global and regional estimates of agriculturalGHG mitigation potential

8.4.3.1 Technical potential for GHG mitigation in agriculture

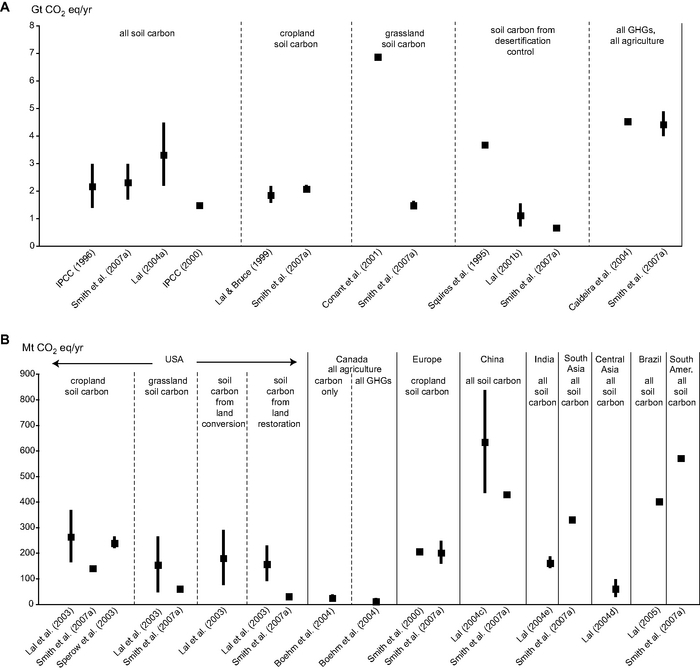

There have been numerous attempts to assess the technical potenttial for GHG mitigation in agriculture. Most of these have focused on soil carbon sequestration. Estimates in the IPCC Second Assessment Report (SAR; IPCC, 1996) suggested that 400-800 MtC/yr (equivalent to about 1400-2900 MtCO2-eq/yr) could be sequestered in global agricultural soils with a finite capacity saturating after 50 to100 years. In addition, SAR concluded that 300-1300 MtC (equivalent to about 1100-4800 MtCO2-eq/yr) from fossil fuels could be offset by using 10 to15% of agricultural land to grow energy crops; with crop residues potentially contributing 100-200 MtC (equivalent to about 400-700 MtCO2-eq/yr) to fossil fuel offsets if recovered and burned. Burning residues for bio-energy might increase N2O emissions but this effect was not quantified.

SAR (IPCC, 1996) estimated that CH4 emissions from agriculture could be reduced by 15 to 56%, mainly through improved nutrition of ruminants and better management of paddy rice, and that improved management could reduce N2O emissions by 9-26%. The document also stated that GHG mitigation techniques will not be adopted by land managers unless they improve profitability but some measures are adopted for reasons other than climate mitigation. Options that both reduce GHG emissions and increase productivity are more likely to be adopted than those which only reduce emissions.

Of published estimates of technical potential, only Caldeira et al. (2004) and Smith et al. (2007a) provide global estimates considering all GHGs together, and Boehm et al. (2004) consider all GHGs for Canada only for 2008. Smith et al. (2007a) used per-area or per-animal estimates of mitigation potential for each GHG and multiplied this by the area available for that practice in each region. It was not necessary to use baseline emissions in calculating mitigation potential. US-EPA (2006b) estimated baseline emissions for 2020 for non-CO2 GHGs as 7250 MtCO2-eq in 2020 (see Chapter 11; Table 11.4). Non-CO2 GHG emissions in agriculture are projected to increase by about 13% from 2000 to 2010 and by 13% from 2010 to 2020 (US-EPA, 2006b). Assuming a similar rate of increase as in the period from 2000 to 2020, global agricultural non-CO2 GHG emissions would be around 8200 MtCO2-eq in 2030.

The global technical potential for mitigation options in agriculture by 2030, considering all gases, was estimated to be ~4500 by Caldeira et al. (2004) and ~5500-6000 MtCO2-eq/yr by Smith et al. (2007a) if considering no economic or other barriers. Economic potentials are considerably lower (see Section 8.4.3.2). Figure 8.3 presents global and regional estimates of agricultural mitigation potential. Of the technical potentials estimated by Smith et al. (2007a), about 89% is from soil carbon sequestration, about 9% from mitigation of methane and about 2% from mitigation of soil N2O emissions (Figure 8.4). The total mitigation potential per region is presented in Figure 8.5.